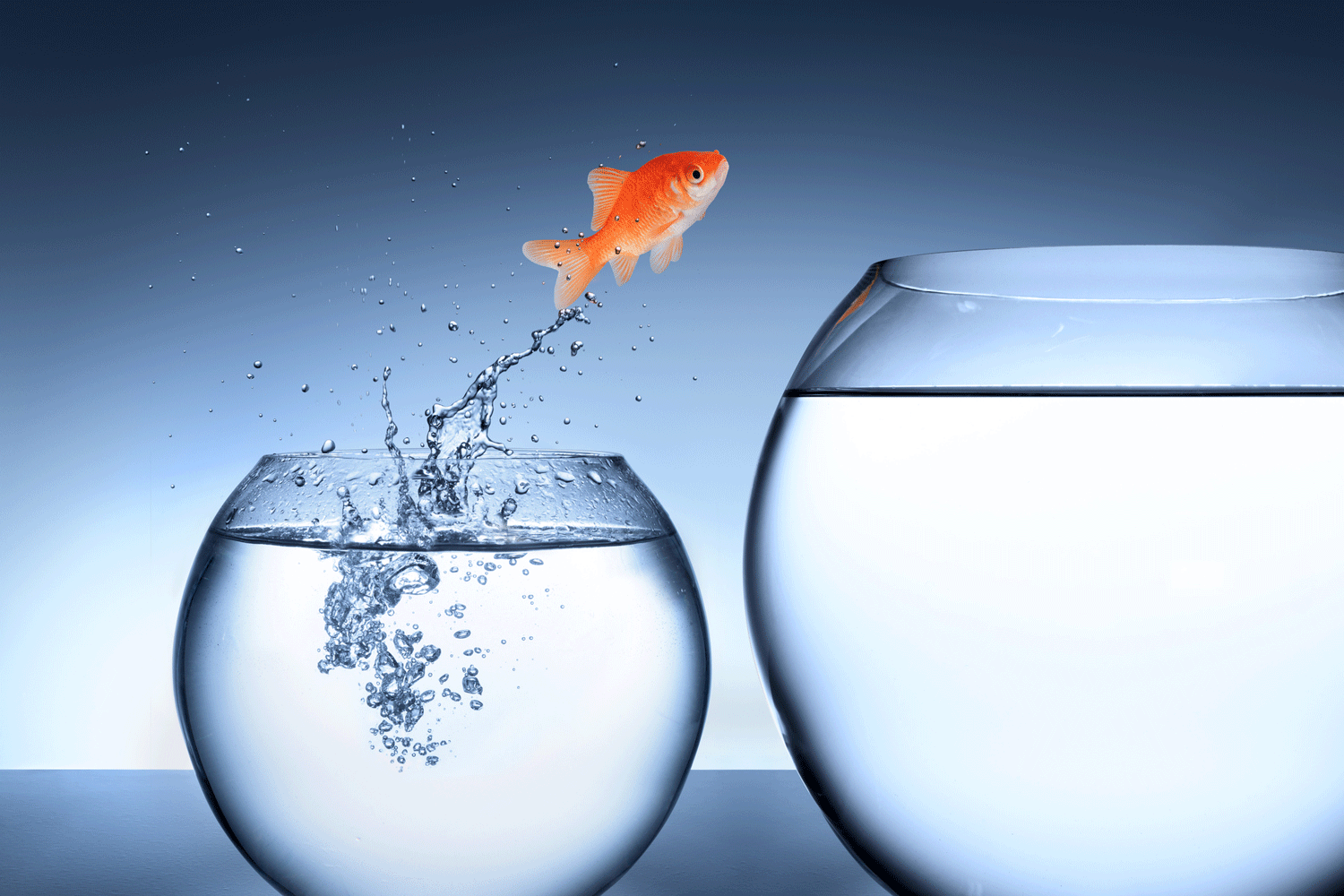

Investing in the good, the bad, and the ugly

by Ben Inker, GMO LLC via Wells Fargo Asset Management

Many investors believe that if an economy is good—that is, growing—stock values will grow right along with it and that stock markets in bad or ugly economies will be left behind. A smart asset allocation, in that case, would be to target countries that are growing the fastest and avoid those whose economies are struggling. Such a strategy, however, would have underperformed historically, as gross domestic product (GDP) doesn’t neatly track stock market returns. In fact, stocks in slower-growing economies have, on average, outperformed those in their better-performing counterparts. Instead of focusing on GDP, investors might instead target valuations, a metric for which history shows much more explanatory power. Many investors believe that GDP growth strongly influences stock market returns. If that were true, the challenge would be the difficulty of predicting GDP growth in time to invest accordingly. The analysis in Chart 1, however, sidesteps the prediction problem by restricting the time period to the past 35 years and assuming that the investor had perfect foresight as to what GDP growth would be.

And the answer is that you could indeed have used knowledge about GDP growth to make money, although not in the expected way. The lowest growth quartile of countries outperformed the highest growth by 2% per year, enough to make a dollar invested worth 85% more in the slow growers than in the fast growers.

Chart 1:

The countries with the fastest GDP growth had a slight tendency to underperform those that had the slowest growth. The correlation between GDP growth and stock market returns was negative (albeit the relationship was not particularly strong). The biggest reason for this nonintuitive result is that there hasn’t been a long-term relationship between GDP growth and earnings per share (EPS) growth. For example, Sweden and Switzerland had strong EPS growth and lower-than-average GDP growth. Canada and Australia, by contrast, had strong GDP growth but showed very little aggregate EPS growth.

Why? One big reason is dilution. Canada and Australia saw strong growth from companies in their commodity-producing sectors, but that growth came from massive investment by the companies, which was funded by diluting shareholders through the sale of additional shares of stock. Companies in Switzerland and Sweden did not invest as much and shareholders did not experience dilution, leaving them better off despite lower economic growth.

Valuation has been a more reliable indicator

While the GDP picture was counterintuitive, there was a piece of knowable information that would have been extremely helpful in predicting returns over the same time span: valuations.

Chart 2:

There was a strong relationship between starting stock valuations and future returns, as shown in Chart 2, with a correlation of -0.78. (Correlation is measured on a scale of 1 being a perfect correlation, 0 being no correlation at all, and -1 being a perfect negative correlation.) We divided the stock markets in the countries included in the study into quartiles and found that the quartile of countries with the cheapest stock prices outperformed the most expensive quartile by 5.1 percentage points per year for 35 years. A dollar split among countries in the cheapest quartile would have grown to $26.40 in real terms, while a dollar invested in the expensive countries would have grown to only $4.90. And that is from price/earnings ratio using historical data, information readily knowable at the time.

Investors aren’t crazy to believe that GDP growth is related to stock market performance. Over shorter-term periods, GDP growth and stock returns often move in the same direction. The problem is our research shows that, based on historical stock performance, the GDP growth that really mattered was not the growth that most investors assumed was going to happen, but the growth that came as a surprise. And predicting surprises is a notoriously tricky problem. Value, on the other hand, takes only information that is freely available to all market participants.

Looking through the lens of valuation, we believe that equity markets are priced to deliver below-average returns, even negative in certain cases. Within equity markets, we have a strong preference for international equities over U.S. equities despite the widely held view that GDP growth will be more robust in the U.S. (the good) than in developed foreign markets (the bad and the ugly). Within international stocks, we believe value stocks are priced to deliver a higher return than growth stocks, and emerging markets value stocks remain our favored equity asset class. We still have a preference for higher-quality stocks within the U.S. given their meaningfully higher expected returns and relative defensive characteristics in both recessions and market declines. Despite all the worrying features of the economic environment outside of the U.S. today, we believe that investing in the various bad and ugly places in the world could wind up far more rewarding than the admittedly good-looking U.S.