Economic growth in the very long run

We cannot take the economic good fortune of the modern world for granted

by Michela Coppola, ProjectM Online

In the long run, we are all dead,” John Maynard Keynes once bluntly stated. True, but should the notion of “long term” be defined by the average human life span? Issues we confront today, such as demographic aging and the challenge of sustaining growth, cannot be understood by examining a few brief decades. Sometimes the roots of economic and societal change trace back centuries.

In this article

- Recreating the historical origins of economic activity

- The Great Enrichment with a surge in living standards and life expectancy

- Why did some countries achieve faster growth or higher income levels than others?

- Productivity and demography threaten wealth of Western countries

Angus Maddison, who died in 2010, understood this. He believed that “the pace and pattern” of economic activity had deep historical origins. A distinguished economic historian with a “predilection for quantification,” Maddison created a database that is one of the great economic resources of our times. In it, he strived to recreate the past by calculating the size and growth rate of the international economy going back to Year 1.

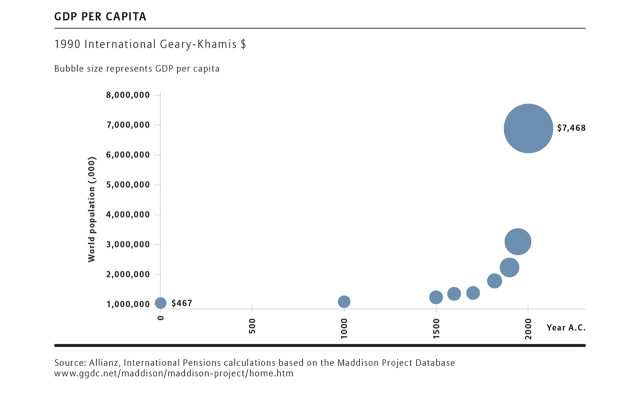

What emerges is an incredible success story. Maddison estimated that over the past millennium, population rose 23-fold while per capita income increased 14-fold. In the previous millennium, population rose only by a sixth and per capita GDP actually fell slightly from 1 CE.

THE GREAT ENRICHMENT

What is astounding is that from 1000 until about 1820, development was a crawl, and abject poverty, which the World Bank puts at $1.25 a day, was the experience for almost all of humanity. After 1820 came a surge in living standards and life expectancy. This period has been dubbed by noted economist Deidre McCloskey as “the Great Enrichment.” Exactly how great was this enrichment? If GDP growth per capita over the last 2010 years was depicted in a 24-hour clock, 80% would occur in the last 40 minutes before midnight.

FROM A LONG-TERM PERSPECTIVE, RICH SOCIETIES ARE THE EXCEPTION RATHER THAN THE RULE

This does not mean the period before lacked growth. Maddison believed that economies do not “take off” from nowhere. In his work, he tried “to explain why some countries achieved faster growth or higher income levels than others.” In Europe, the complex interaction between proximate (directly measurable economic inputs, such as labor, physical and human capital, and land) and ultimate (institutional, political, social and cultural) sources of growth accumulated over centuries. Eventually it provided a productivity burst that allowed Europe to take economic leadership from China around 1500 onwards.

Yet, although there were huge differences in the technological capabilities of countries before 1820, living standards of the average person were similar across countries. This is because the population densities in technologically advanced countries were rising. While the size of the cake was increasing, more people were eating it, so everyone still received a thin sliver.

Maddison’s data shows that in 1820 an average inhabitant in the richest regions had a GDP per capita three times higher than someone in the poorest region. Since then the spread has widened. By 2001, the gap between the richest and the poorest region was 18 to 1.

Two trends are widening this gap. First, productivity in industrialized countries dramatically outpaced the rest of the world – increasing the size of the cake. Second, in industrialized countries, population growth peaked in the 19th century and – with the exception of the postwar baby boom – has fallen ever since, allowing the Western world to reap a demographic dividend.

As the population size stabilized and productivity rose, the size of the average slice of cake has increased. Lower birth rates and increasing life spans also had a positive effect on the accumulation of human capital: fewer children meant parents could invest more resources on the children they had. As a result, labor productivity increased further, allowing the cake to become even larger.

DECLINING TIMES

A historic irony is that the two factors – productivity and demography – that underlined the economic success of Western countries in the last two centuries are now threatening their wealth. With the number of workers set to decline, the goods and services available per person will shrink. As the pool of labor shrinks, improving longevity means the number of consumers will remain constant. The result, a smaller cake for roughly the same number of people.

This decline could be significant. Assuming all else remains equal (output per hour, hours worked and labor force participation), Germany risks losing 15% of its GDP per capita by 2035. The pattern is similar in other mature economies.

Governments can address this through policies that expand the labor force to use the underutilized skills of the elderly and women. If more workers work until the official retirement age, current levels of GDP per capita could be sustained for some time. Equally, encouraging more women to join the workforce would soften the effects of aging on economic potential growth.

Increasing labor productivity is another key. For example, by 2035, German workers would need to produce 17% more per working hour in order to hold GDP per capita constant. Achieving this will be tricky. Between 1870 and 1990, average output increased by a factor of 17, but the easy targets have already been hit. Pushing the productivity frontier further will require much more concerted effort.

In less than two centuries, a bare 40-minute window on the two-millennia clock, living standards have experienced a quantum leap. However, the wealth of goods and services enjoyed today is an anomaly when seen from the long term. To retain these gains, businesses, governments and societies need to deal with the challenges of demographic aging by fostering productivity increases and adjusting to an older labor force. Given the speed of demographic change in many parts of the world today, time is not on our side.

Copyright © ProjectM Online