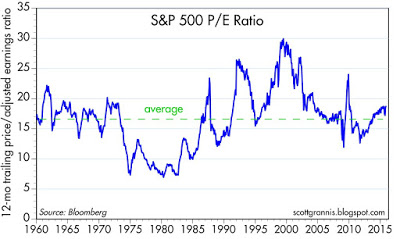

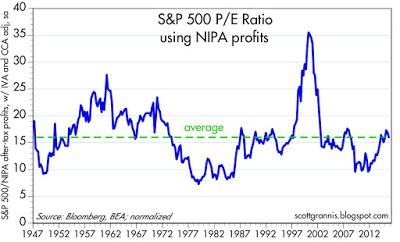

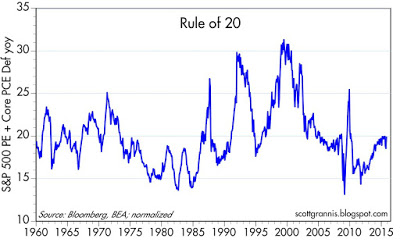

Corporate profits are impressive, but valuations are merely average

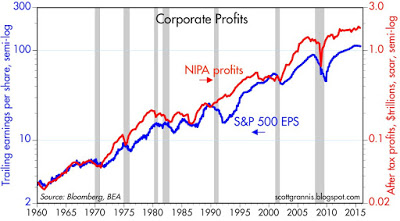

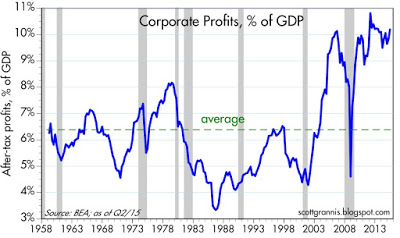

With last week's release of revised GDP statistics for Q3/15, we learned that after-tax corporate profits in the 3rd quarter were down 3.2% from the second quarter, but were up 1.4% from year-ago levels. The growth in profits has slowed significantly in recent years, but profits were still 9.9% of nominal GDP last quarter, just shy of their all-time high of 10.8%, which was set three and a half years ago. To put that in perspective, consider that after-tax corporate profits have averaged about 6.5% of nominal GDP since 1959, and as recently as 11 years ago, profits had never exceeded 8% of GDP.

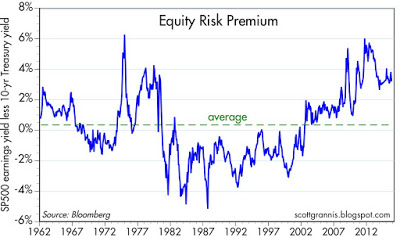

Caution is also reflected in the chart above, which shows the difference between the earnings yield on stocks (the inverse of PE ratios) and the yield on 10-yr Treasuries. In order to satisfy investors' aversion to risk, the market demands a yield on stocks that is about 4% higher than the yield on safe Treasuries. Today's equity risk premium is substantially higher than its long-term average.