The ghost of 1937: The fed stalls on rate hike

by Ron Rimkus, CFA, via CFA Institute

The eyes of the world were on the US Federal Reserve today. Would it or would it not raise interest rates? Now we know.

Today, the Fed voted to forgo a rate hike, keeping short-term lending rates near zero.

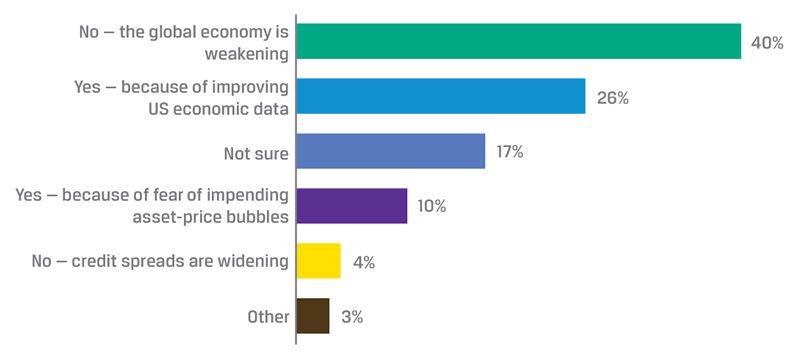

The much anticipated announcement ends seemingly endless rounds of speculation and punditry. To get a feel for market expectations in the lead-up to the announcement, we asked our esteemed CFA Institute Financial NewsBrief readers if they thought the Fed would raise rates. Of the 694 participants, 44% said no, with the vast majority of these respondents citing the weakening global economy. In contrast, 36% of respondents said yes, with most pointing to improving US economic data. Approximately 17% indicated that they were not sure what the Fed would do, while roughly 3% selected the “Other” category.

Will the US Federal Reserve hike interest rates at its meeting on Thursday?

Now that the question of what the would Fed do has been answered, we now turn to why. Why did the Fed delay a rate hike? Or, more pointedly, why didn’t the Fed choose to depart from the extraordinary policy that has been in place since the crisis of 2008?

In today’s press release, the Fed stated, “Recent global economic and financial developments may restrain economic activity somewhat and are likely to put further downward pressure on inflation in the near term.” Could it be that the Fed is afraid of repeating the mistakes of 1937? The comparison is noteworthy.

In 1937, the United States was approximately seven years into the Great Depression. Today we are seven years removed from the financial crisis of 2008. The policy response of the Fed in the 1930s is best characterized as two distinct mini-periods. At the onset of the Great Depression in 1929–1930, the Fed maintained a “hands-off” approach, believing the economy simply needed to “wring out its excesses.” This is somewhat ironic in that Fed policy itself greatly contributed to the financial excesses of the 1920s. Nevertheless, the Fed failed to recognize the nature of the economy.

When the Great Depression hit in 1929, the Fed’s instinct was to do little and let the economy and markets correct. But the Fed seemed to have no sense of how big the credit bubble from the 1920s was. Consequently, from 1929–1933, the Fed remained committed to a tight monetary policy. Under the gold standard then in force, when the gold balances held by the government contracted, the money supply did so as well. Faced with the increasing economic turmoil, US businesses and the public at large trusted gold more than paper currency. Overseas investors, fearing a potential devaluation of the dollar, preferred gold too. This created a gold drain. As the Fed’s gold stocks declined, the United States unwittingly reduced credit in the economy. Over the 1929–1933 period, the US money supply contracted sharply, declining by roughly one third between 1929 and 1933, and the country experienced its worst ever downturn, with unemployment soaring to roughly 25%.

In 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, backed by Congress, took the country off the gold standard. This caused the money supply to expand rapidly in the years immediately following. The policy worked and the fortunes of the US economy began to improve. By late 1936, however, the Fed started to worry that excess liquidity and credit growth might lead to accelerated inflation. So it took the initiative to soak up the excess reserves on bank balance sheets by increasing the reserve requirement ratio (the equivalent of tightening the money supply). Rather than absorb the excess liquidity, however, this move forced the US economy back into recession. Banks were still worried about a resurgence of economic weakness and, therefore, wanted to maintain greater reserves to protect against a downturn. So, as the Fed elevated the reserve requirement ratio, banks reduced lending. Between May 1937 and June 1938, US GDP contracted by 9%.

From a Fed policy perspective, the lesson here is that the 1933–1937 period is similar to the environment today, while the 1929–1933 period is not. Perhaps the greatest difference is that the economy today has had roughly seven years to recover, while the 1930s period had only four. Nevertheless, the global economy is faltering, capital is fleeing emerging markets, and the dollar is rising. All of this suggests that inflationary forces are declining.

Looks like the ghost of 1937 is haunting the Fed.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Copyright © Ron Rimkus, CFA, via CFA Institute