by Rick Ferri

I was a brand-spanking new Second Lieutenant in the Marine Corps 35 years ago. We graduated 135 “butter-bars” from my Officer Candidate class. We were called that because the single, brass bar rank insignia looks like a bar of butter. We had a lot of pride and ambition on commissioning day, and all the opportunity in the world to advance in the Marine Corps.

The top officer rank in the Marines is General. Not one of the fine officers with whom I was commissioned made it that far. (I retired as a reserve Major in early 2001.) General isn’t an easy rank to reach. According to the Marine Corps Almanac, there were only 83 active duty Generals out of nearly 30,000 total officers as of March 11, 2015. That’s less than one-half of one percent.

Becoming a General requires decades of service and commitment, impeccable personal stature and integrity, years spent away from home and family, and more than a little luck. The officers in my commissioning class didn’t make it for various reasons. Most left the Corps for a civilian career when their commitment was over. Others retired when they were able. A few were stopped short because they made the ultimate sacrifice for their country. I decided to focus on an investment career after eight years in the Corps, and that ended my General pursuit.

What does this have to do with investing and your portfolio? I’m always struck by the similarities between a military career and a career as a mutual fund manager. Thousands of people are recruited into the fund industry each year. A few will get a chance to manage large fund portfolios. These new managers step into their role with pride, ambition, and the intent to become top in their field. Yet, only a handful of those few reach stardom in their lifetime – the equivalent of a General’s rank in the mutual fund world, if you will. The rest never make it.

Persistence of performance is probably the biggest culprit that interferes with a manager’s ability to ascend to and, harder still, retain their stardom. It’s extremely difficult for managers to remain in the top quartile or even the top half of their peers year after year. Top fund managers routinely fall off their perches. Those who end up at the bottom often see their funds merged or closed by the fund companies they work for. Their names are soon lost to history, but the rise and fall of their fund performances are captured semi-annually by the S&P Dow Jones Indices Persistence Scorecard.

According to S&P Dow Jones Indices research, relatively few funds are able to maintain consistently good performance. Out of the 682 US equity funds that were in the top quartile in March 2013, only 5.28% of them remained in that top quartile at the end of March 2015. Looking for persistent performance by asset class didn’t help either. During the same timeframe, only 3.95% of large-cap funds, 5.26% of the mid-cap funds, and 4.67% of small-cap funds that started in the top quartile remained there. All the other past “winners” had fallen behind in the competition; some were merged or closed by the fund companies entirely.

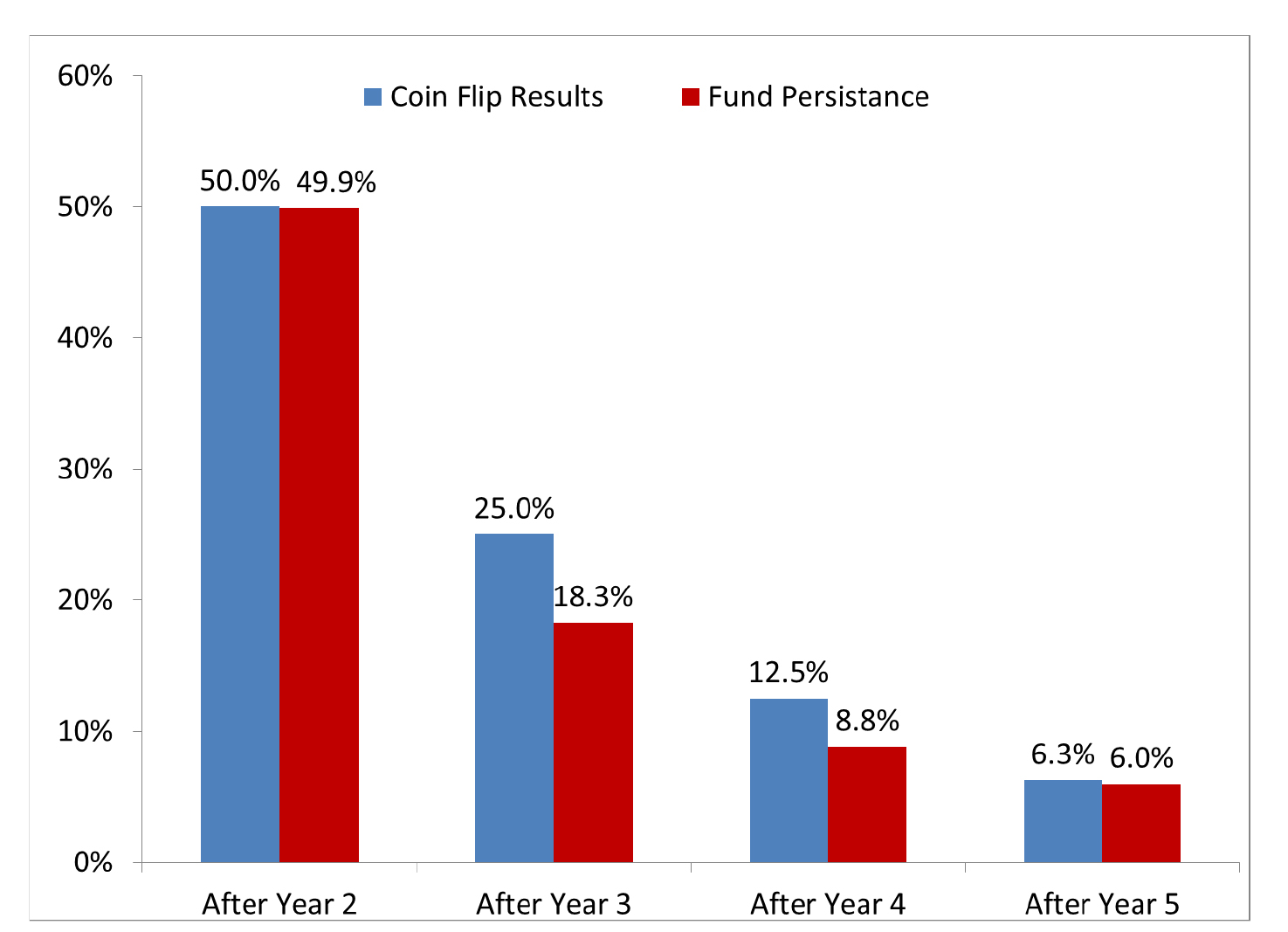

It’s even difficult for a fund to stay in the top half of fund performance for more than a couple of years. Figure 1 illustrates this difficulty. The red bar represents the percentage of winning US equity funds that remained in the top half of all US stock funds for consecutive years and the blue bar is a random coin-flip probability of a repeating occurrence. Each coin flip entails a random, 50/50 shot at an occurrence of heads or tails. This means the odds of flipping the same occurrence twice in a row is 50%, three times in a row is 25%, and so on. As you can see, fund managers face even tougher odds than random chance would suggest.

Figure 1: US equity fund persistence of top-half performance

Source: Data from S&P Dow Jones Indices, “Does Past Performance Matter? The Persistence Scorecard,” June 2015, chart by Richard Ferri.

Marine Corps Second Lieutenants and new fund managers have a lot in common. Their ambition is high and their desire to prove themselves is strong, but only a select few will beat the steep odds against them and reach the top in their profession. The work, skill and luck required to get to the star level is daunting. Few have what it takes to begin with, and equally hard-working, skillful and/or lucky competitive peers are ever ready to step in when one in their rank falters.

Trying to select a Second Lieutenant who will become a General or a fund manager who will persistently outperform the markets is a futile endeavor. Nobody knows beforehand who the stars will be. Nobody has designed a career indicator that can predict this with any degree of accuracy.

For investors, there is a better way. Index funds match the indexes they track, less a small fee. A portfolio of low-cost index funds ensures you get your fair share of the market’s return. It’s a way to tilt the odds in your favor and win the investment war without having to try your luck at beating the incredibly steep odds involved in predicting persistently winning managers.

Copyright © Rick Ferri