by Cullen Roche, Pragmatic Capitalism

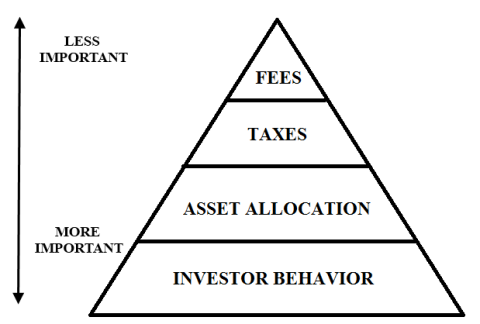

I really liked this post by Morgan Housel on the Hierarchy of Investor Needs. Morgan provides a very simple way of prioritizing the investment process. I’ve changed his hierarchy just a little bit and I wanted to quantify and expand on the process of prioritizing each:

Let’s just take the Global Financial Asset Portfolio (the one true benchmark for the world’s financial markets) and make some simple assumptions going forward. We know this portfolio is roughly 45/55 stocks/bonds at present. Let’s be aggressive and assume that stocks generate 10% returns (John Bogle says 7%, and there are more than a few macro indicators that are consistent with low future returns, but who knows). And then let’s just assume that bonds will generate about 2.5% which is pretty close to what an aggregate index is generating these days. That gets us to about 7% in the aggregate.

Behavior is, arguably by a wide margin, the most important component of the hierarchy because it is multiplied through many of the other components. An investor who gets scared in and out of the markets or doesn’t have a sound process will likely end up underperforming a correlated index and will also incur taxes and fees along the way. Vanguard has estimated that behavioral coaching alone can add 150 bps to a portfolio. So, let’s just assume bad behavior is worth about -1.5% per year or about 21% of that top line 7% return.

Asset allocation will steer the performance of your portfolio. It’s well known in modern finance that asset allocation is the primary driving factor behind portfolio performance. I’ve removed “security selection” from Morgan’s hierarchy because I don’t think anyone should be picking stocks inside of a savings portfolio. There’s just no reason to add individual company risk to a portfolio when we know we can diversify into assets that will very likely perform with a high correlation to a set of chosen individual securities. Vanguard estimates that proper asset allocation is worth about 0.75% per year.

Most investors don’t consider how important taxes are in their investment approach, but they’re often times more important than fees. In fact, I’ve placed them lower on the hierarchy here because I think taxes are becoming more important than fees. That is, if we generate 7% returns in short-term capital gains and pay the highest tax rate of 38% then we’re paying the equivalent of a 2.77% fee to the tax man. Of course, you have to pay taxes anyhow, but the long-term rate of 20% in the highest tax bracket will reduce the tax man’s fee by almost HALF at 1.4%. So, taxes actually end up being a bigger fee than even the average financial advisor who charges 1% (plus underlying fund expenses).

Fees are still super important though. As I’ve shown in the past, the difference between paying a 0.9% fee and a 0.1% fee will add up to $150,000 in fees over a 30 year period. That’s a staggering figure. But in today’s world of low fee ETFs and index funds there’s really no reason to pay high fees. My general rule of thumb is to never pay more than 0.5% in fees per year (including an advisory fee if you work with an advisor).

Follow these simple guidelines and you’re likely to vastly improve your odds of financial success.

Copyright © Pragmatic Capitalism