by Robert P. Seawright, Above the Market

We all lie, especially to and about ourselves. Sometimes the lies are overt. Sometimes they are unintentional. Sometimes they are sales puffery. And sometimes they are devious. What follows are ten great lies in the financial services industry. The first three are propagated primarily by academic finance.

The fourth is within the province of the academics but is a bigger problem amongst the professionals – advisors and money managers alike. The next three are predominantly professional lies.

Number eight is asserted most often by the professional class and believed by consumers while the last two are universal but play out most unfortunately amongst consumer investors. I’m sure there are more. Do you have others to suggest?

Here goes….

1. We’re rational, utility-maximizing creatures. This is a really big lie propagated by academic finance. Anyone with even an ounce of self-awareness knows we’re anything but rational far too often. We are driven by emotions such as fear, greed and ego and beset by myriad cognitive flaws that make it monumentally hard for us to make good decisions, especially about money. Anyone who lived through the dotcom bubble (Pets.com!) can only laugh at this silly idea that we’re cool rationalists (while recalling Chuck Prince, the ousted Citibank CEO, and his infamous line: “As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance,” or this Jim Cramer speech). On our best days, when wearing the right sort of spectacles, squinting and tilting our heads just so, we can be observant, efficient, loyal, assertive truth-tellers. However, on most days, all too much of the time, we’re delusional, lazy, partisan, arrogant confabulators.

1. We’re rational, utility-maximizing creatures. This is a really big lie propagated by academic finance. Anyone with even an ounce of self-awareness knows we’re anything but rational far too often. We are driven by emotions such as fear, greed and ego and beset by myriad cognitive flaws that make it monumentally hard for us to make good decisions, especially about money. Anyone who lived through the dotcom bubble (Pets.com!) can only laugh at this silly idea that we’re cool rationalists (while recalling Chuck Prince, the ousted Citibank CEO, and his infamous line: “As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance,” or this Jim Cramer speech). On our best days, when wearing the right sort of spectacles, squinting and tilting our heads just so, we can be observant, efficient, loyal, assertive truth-tellers. However, on most days, all too much of the time, we’re delusional, lazy, partisan, arrogant confabulators.

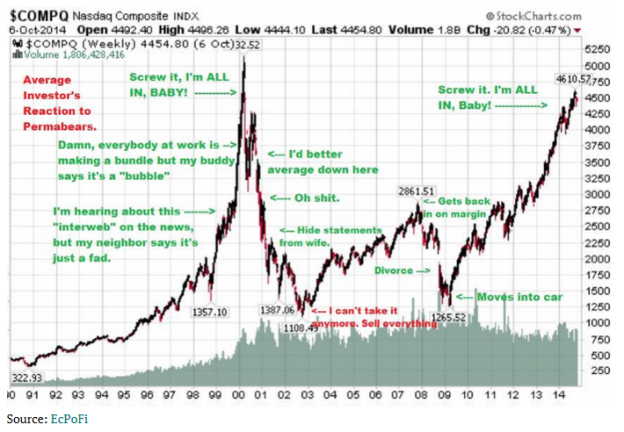

2. The markets are efficient. It’s preposterously easy to falsify this claim. Simply look at this chart (at right) and try to provide a substantive basis for the huge differences in value before and after the major price drops reflected thereby. Go ahead. Take your time. However, I also hasten to add that the ease with which one can falsify the efficient markets hypothesis is entirely matched by the difficulty faced by investors in trying to beat the market. It’s monumentally difficult to exploit even obvious market inefficiencies (most often because they seem obvious only in retrospect).

2. The markets are efficient. It’s preposterously easy to falsify this claim. Simply look at this chart (at right) and try to provide a substantive basis for the huge differences in value before and after the major price drops reflected thereby. Go ahead. Take your time. However, I also hasten to add that the ease with which one can falsify the efficient markets hypothesis is entirely matched by the difficulty faced by investors in trying to beat the market. It’s monumentally difficult to exploit even obvious market inefficiencies (most often because they seem obvious only in retrospect).

3. Risk and volatility are the same thing. Risk and volatility are hardly the same thing. Using volatility as a stand-in for risk makes the requisite academic finance equations work out neatly and all, but since nobody is bothered by upside volatility, it isn’t even a very rough approximation. Moreover, in the real world, buying a highly volatile market that is extremely cheap (think March of 2009) is among the safest plays imaginable. And, practically speaking, the only risk that really matters in the long-run is the permanent loss of capital. Volatility doesn’t help much in avoiding that.

3. Risk and volatility are the same thing. Risk and volatility are hardly the same thing. Using volatility as a stand-in for risk makes the requisite academic finance equations work out neatly and all, but since nobody is bothered by upside volatility, it isn’t even a very rough approximation. Moreover, in the real world, buying a highly volatile market that is extremely cheap (think March of 2009) is among the safest plays imaginable. And, practically speaking, the only risk that really matters in the long-run is the permanent loss of capital. Volatility doesn’t help much in avoiding that.

4. Simplicity doesn’t matter. Academics fail here: “Page after page of professional economic journals are filled with mathematical formulas leading the reader from sets of more or less plausible but entirely arbitrary assumptions to precisely stated but irrelevant theoretical conclusions” (Nobel laureate Wassily Leontief, writing in Science, Volume 217, 9 July 1982, p. 106). But the key users of this lie are those in the professional class who offer complexity to try to justify their ongoing existence and their (high) fees. Meanwhile, the behavioral research is clear that too many choices and too much complexity lead to poor choices. I can’t say it any better than Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.: “For the simplicity on this side of complexity, I wouldn’t give you a fig. But for the simplicity on the other side of complexity, for that I would give you anything I have.” But perhaps Einstein did: “Everything should be as simple as possible, but no simpler.” Our world is complex and getting more so. The investment world is now exceedingly complex and going faster every nanosecond. If we’re going to succeed, we need to make things as simple as possible (if no simpler).

4. Simplicity doesn’t matter. Academics fail here: “Page after page of professional economic journals are filled with mathematical formulas leading the reader from sets of more or less plausible but entirely arbitrary assumptions to precisely stated but irrelevant theoretical conclusions” (Nobel laureate Wassily Leontief, writing in Science, Volume 217, 9 July 1982, p. 106). But the key users of this lie are those in the professional class who offer complexity to try to justify their ongoing existence and their (high) fees. Meanwhile, the behavioral research is clear that too many choices and too much complexity lead to poor choices. I can’t say it any better than Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.: “For the simplicity on this side of complexity, I wouldn’t give you a fig. But for the simplicity on the other side of complexity, for that I would give you anything I have.” But perhaps Einstein did: “Everything should be as simple as possible, but no simpler.” Our world is complex and getting more so. The investment world is now exceedingly complex and going faster every nanosecond. If we’re going to succeed, we need to make things as simple as possible (if no simpler).

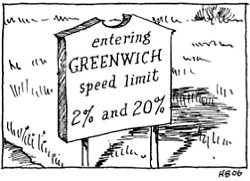

5. Fees don’t matter. That this lie is almost always implicit doesn’t make it any less of a lie (“because I’m worth it”). Neither does the sad reality that many consumers will be less likely to choose a lower fee product or service because they tend to equate price with value. The bottom line is that costs are the best indicator we have of investment success or failure (do I need to add that lower is better?). Fees do matter. A lot.

5. Fees don’t matter. That this lie is almost always implicit doesn’t make it any less of a lie (“because I’m worth it”). Neither does the sad reality that many consumers will be less likely to choose a lower fee product or service because they tend to equate price with value. The bottom line is that costs are the best indicator we have of investment success or failure (do I need to add that lower is better?). Fees do matter. A lot.

6. Market timing works. The whole concept of market-timing not been so utterly discredited (the latest data is here), that it shouldn’t really have to be argued anymore. There are simply too many variables at work and in play to make meaningful predictions about near-to-intermediate term market performance. The investment management business recognizes this problem, but for them it’s a marketing difficulty. Thus there remain many market-timing schemes pushed at customers every day. It’s just not called market-timing anymore. The great William Bernstein states the case really well. “There are two kinds of investors, be they large or small: those who don’t know where the market is headed, and those who don’t know that they don’t know. Then again, there is a third type of investor – [an] investment professional, who indeed knows that he or she doesn’t know, but whose livelihood depends upon appearing to know.”

6. Market timing works. The whole concept of market-timing not been so utterly discredited (the latest data is here), that it shouldn’t really have to be argued anymore. There are simply too many variables at work and in play to make meaningful predictions about near-to-intermediate term market performance. The investment management business recognizes this problem, but for them it’s a marketing difficulty. Thus there remain many market-timing schemes pushed at customers every day. It’s just not called market-timing anymore. The great William Bernstein states the case really well. “There are two kinds of investors, be they large or small: those who don’t know where the market is headed, and those who don’t know that they don’t know. Then again, there is a third type of investor – [an] investment professional, who indeed knows that he or she doesn’t know, but whose livelihood depends upon appearing to know.”

7. Stock-picking works. Like market-timing, stock-picking has also been flatly, utterly and thoroughly debunked. Still, stock-picking funds are sold in large quantities all day every day. I hasten to add that this doesn’t mean that active management (however defined) is also thoroughly debunked. That’s especially so in that, in my view, holding anything other than the “global market portfolio” (which I think would be a lousy asset allocation for most people) is active management. Despite constant claims to the contrary (usually implicit), stock-picking doesn’t work.

7. Stock-picking works. Like market-timing, stock-picking has also been flatly, utterly and thoroughly debunked. Still, stock-picking funds are sold in large quantities all day every day. I hasten to add that this doesn’t mean that active management (however defined) is also thoroughly debunked. That’s especially so in that, in my view, holding anything other than the “global market portfolio” (which I think would be a lousy asset allocation for most people) is active management. Despite constant claims to the contrary (usually implicit), stock-picking doesn’t work.

8. Rich people are different. In a “famous” exchange that apparently never really happened, F. Scott Fitzgerald supposedly stated that rich people are different, to which Ernest Hemingway is said to have replied, “Yes, they have money.” The idea that rich people are different in more ways than the size of their investment accounts is an especially sneaky lie in that it offers an added layer of analytical subtlety. Most of us want to be rich, so we eagerly lap up what we perceive to be the accoutrements of the rich, like expensive cars and hedge funds, thinking they will make us like rich people somehow. Big mistake.

8. Rich people are different. In a “famous” exchange that apparently never really happened, F. Scott Fitzgerald supposedly stated that rich people are different, to which Ernest Hemingway is said to have replied, “Yes, they have money.” The idea that rich people are different in more ways than the size of their investment accounts is an especially sneaky lie in that it offers an added layer of analytical subtlety. Most of us want to be rich, so we eagerly lap up what we perceive to be the accoutrements of the rich, like expensive cars and hedge funds, thinking they will make us like rich people somehow. Big mistake.

9. I’m different (special even!). We all like to think that we live in Lake Wobegon, where all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking and all the children are above average. We like to think that the usual rules of investing and behavior simply don’t apply to us. The typical person can’t control his or her emotions, but I can. It’s really, really hard to beat the market, but I can. Almost nobody can pick good managers ahead of time, but I can. Like Yogi, we’re “smarter than the average bear.” Academics believe it. Finance professionals believe it. And consumers believe it. But there’s not a shred of evidence to support it.

9. I’m different (special even!). We all like to think that we live in Lake Wobegon, where all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking and all the children are above average. We like to think that the usual rules of investing and behavior simply don’t apply to us. The typical person can’t control his or her emotions, but I can. It’s really, really hard to beat the market, but I can. Almost nobody can pick good managers ahead of time, but I can. Like Yogi, we’re “smarter than the average bear.” Academics believe it. Finance professionals believe it. And consumers believe it. But there’s not a shred of evidence to support it.

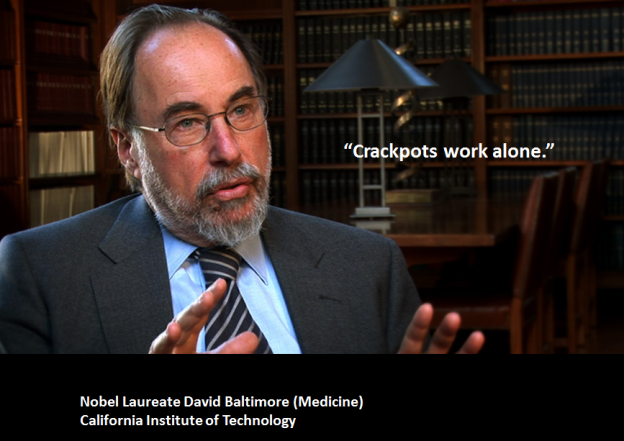

10. I don’t need help. American virologist David Baltimore, who won the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1975 for his work on the genetic mechanisms of viruses, once told me that over the years (and especially while he was president of CalTech) he received many manuscripts claiming to have solved some great scientific problem. Most prominent scientists have drawers full of similar submissions, almost always from people who work alone and outside of the scientific community. Unfortunately, none of these offerings has done anything remotely close to what was claimed, and Dr. Baltimore offered some fascinating insight into why he thinks that’s so. At its best, he noted, good science (like good investing and good thinking) is a collaborative, community effort. On the other hand, “crackpots work alone.” Good collaboration among professionals and with good professionals by consumers improves investment outcomes, usually by a lot. A good professional can offer help with goals and plans, an Investment Policy Statement, asset allocation, risk management, behavioral management, protection from fraud (especially for seniors), and tax, estate and financial planning. We all need more help than we think.

10. I don’t need help. American virologist David Baltimore, who won the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1975 for his work on the genetic mechanisms of viruses, once told me that over the years (and especially while he was president of CalTech) he received many manuscripts claiming to have solved some great scientific problem. Most prominent scientists have drawers full of similar submissions, almost always from people who work alone and outside of the scientific community. Unfortunately, none of these offerings has done anything remotely close to what was claimed, and Dr. Baltimore offered some fascinating insight into why he thinks that’s so. At its best, he noted, good science (like good investing and good thinking) is a collaborative, community effort. On the other hand, “crackpots work alone.” Good collaboration among professionals and with good professionals by consumers improves investment outcomes, usually by a lot. A good professional can offer help with goals and plans, an Investment Policy Statement, asset allocation, risk management, behavioral management, protection from fraud (especially for seniors), and tax, estate and financial planning. We all need more help than we think.

Copyright © Above the Market