by Ben Carlson, A Wealth of Common Sense

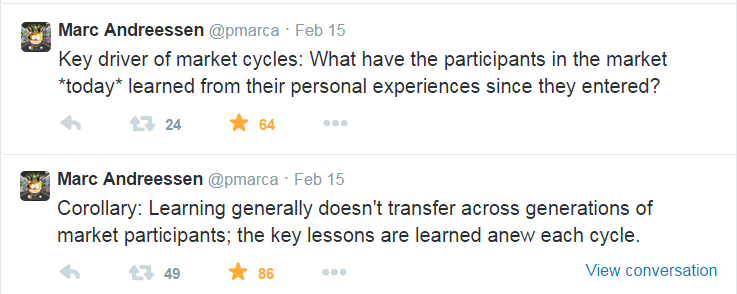

Mark Andreessen laid out some interesting theories on Twitter earlier this week about market cycles:

Traders like to say that the market has no memory from day to day. But when stocks are only up roughly 53% of all trading days, any single market session is going to be very noisy. What really matters are longer-term trends and the perception of risk by market participants. Benoit Mandelbrot described in his book The (mis)Behavior of Markets what Andreessen was talking about when he looked the emotional scars left on those who lived through the Great Depression:

Traders like to say that the market has no memory from day to day. But when stocks are only up roughly 53% of all trading days, any single market session is going to be very noisy. What really matters are longer-term trends and the perception of risk by market participants. Benoit Mandelbrot described in his book The (mis)Behavior of Markets what Andreessen was talking about when he looked the emotional scars left on those who lived through the Great Depression:

In the 1960s, some old-timers on Wall Street – the men who remembered the trauma of the 1929 Crash and the Great Depression – gave me a warning: “When we fade from this business, something will be lost. That is the memory of 1929.” Because of that personal recollection, they said, they acted with more caution than they otherwise might. Collectively, their generation provided an in-built brake on the wildest forms of speculation, an insurance policy against financial excess and consequent catastrophe. Their memories provided a practical form of long-term dependence in the financial markets. Is it any wonder that in 1987, when most of those men were gone and their wisdom forgotten, the market encountered its first crash in nearly sixty years? Or that, two decades later, we would see the biggest bull market, and the worst bear market, in generations? Yet standard financial theory holds that, in modeling markets, all that matters is today’s news and the expectations of tomorrow’s news.

As investors we’re all shaped by our experiences, whether we choose to believe it or not. And it’s not only the Depression babies. Investors in the 1970s were scarred from runaway inflation and poor stock and bond market returns. Investors in the 1980s and 1990s were led to believe that stocks offered high double-digit annual returns year in and year out. The 2000s left investors feeling that the markets were nothing more than a casino with the odds heavily stacked against them.

But you get the feeling that the market crashes leave the most indelible memories on investor psyches. Andre Agassi discussed the pain of losing in his book Open: An Autobiography:

But I don’t feel that Wimbledon changed me. I feel, in fact, as if I’ve been let in on a dirty little secret: winning changes nothing. Now that I’ve won a slam, I know something that very few people on earth are permitted to know. A win doesn’t feel as good as a loss feels bad, and the good feeling doesn’t last as long as the bad. Not even close.

In market parlance, what Agassi is describing here is that there aren’t many lessons learned during a bull market because everyone thinks they’re a genius. He also illustrates the power of loss aversion which is why the old saying goes that markets climb a wall of worry. The wall of worry doesn’t exist because people misinterpret data. It’s because they remember what a market crash feels like and it’s always in the back of their mind.

Which begs the question: What memories or lack thereof could affect the markets in the future?

The first one that comes to mind is the fact that there are very few investors that have lived through a rising interest rate environment and a bond bear market. Fixed income investors have been living in a falling interest rate regime since the early 1980s. If and when the bond bull market ends there are bound to be over- and under-reactions by investors. It will also be very telling to see which bond managers were a product of a bull market and which ones can navigate a difficult environment.

The way I see it there were three basic lessons that most investors took away from the 2008 crash and its aftermath: (1) Some people learned that they can’t handle investing in stocks after seeing two crashes during the same decade and have more or less given up investing in the stock market. (2) Others learned that the markets seem to always come back and have conditioned themselves for that response. (3) Still others learned nothing because it’s very easy to sweep your mistakes under the rug.

These memories and experiences will likely lead to some fascinating behavior depending on future market outcomes. What if stocks and bonds are both negative during the same year? It’s something that hasn’t happened in the U.S. since 1969, but it’s possible after the huge run-up in both stocks and bonds. How would investors react under that scenario? Or what if we do have another market crash? Would an entire generation of investors (my fellow Millennials) give up on stocks for good because they’ve witnessed so much carnage in the markets in their lifetime?

I started out my career in the investment business during the aftermath of the tech bubble. Next I saw the rise of the real estate and global credit bubble only to watch it all come crashing down during the Great Financial Crisis. Since then the recovery in the financial markets has been massive. These experiences, for better or for worse, will shape my future views on the markets in some way. Investors would be wise to consider how their own memories and experiences will shape their future outlooks of market cycles.

Sources:

The (mis)Behavior of Markets

Open: An Autobiography

Further Reading:

Pattern Recognition

Is Technology Speeding Up Market Cycles

Subscribe to receive email updates and my monthly newsletter by clicking here.

Follow me on Twitter: @awealthofcs

Copyright © Ben Carlson, A Wealth of Common Sense