The U.S. equity market is expensive.The median stock is about as pricey as it’s been in 50 years, and valuations are all clustered:there are far fewer bargains than in years past. I am not an index investor, so I generally pay less attention to market-level valuation measures like the Shiller P/E or Tobin’s Q—but both show the U.S. market as expensive. These valuation tools are more strategic than timing tools, but both signals advise caution.

What’s strange, then, is how little attention global equities get. The debate is all about the U.S. market, which represents less than half of the global stock market. But today, non-U.S. equities are cheaper than U.S. equities, with more bargains to be had. One simple example: among companies with a market cap greater than $200MM, there are about 100 companies in the U.S. that still have a price-to-earnings multiple below 10; there are more than 550 Non-U.S. stocks with a P/E below 10.

American investors need to diversify globally, because having all one’s risk tied up in one market doesn’t make sense—especially when that market is the most expensive developed market in the world. It’s not just because valuations are better abroad, but because history teaches us again and again that individual country markets can have long, tumultuous periods of negative returns. Luckily, the global market portfolio usually holds up well.

Portfolio Patriotism

The preference to own companies in one’s home country is one of the most pervasive and persistent biases in investing. We prefer familiar companies that offer products or services that we use and know. Lots of U.S. investors own Coke, but very few own Suntory (a Japanese drinks company). The overweight to home countries is often extreme. In 2010, the U.S. market was roughly 43% of the global stock market, but U.S. investors had 72% of their portfolios allocated to U.S. stocks. It’s much worse in smaller countries like Canada and the U.K. In 2010, Canadian stocks were roughly 5% of the global market, but Canadian investors had a 65% allocation to their domestic market (the U.K. was very similar: 8% of the global market, but U.K. investors had a 50% allocation)[i].

If you believe in index investing, then a “neutral” or “passive” portfolio would be the MSCI All-Country World Index or some similar benchmark, but few portfolios look like the ACWI. Even though the U.S. has been the dominant stock market for more than 100 years, there are compelling reasons to own a more global portfolio.

Using the incredible long-term global equity market data built by Dimson, Marsh, and Staunton, we can review the history of individual country equity markets to make the case that you should not bundle all your risk into one country. There have been many examples of disaster within one market, so to think that similar disasters won’t happen in the future is naïve. Throughout it all, the global equity portfolio has held up remarkably well.

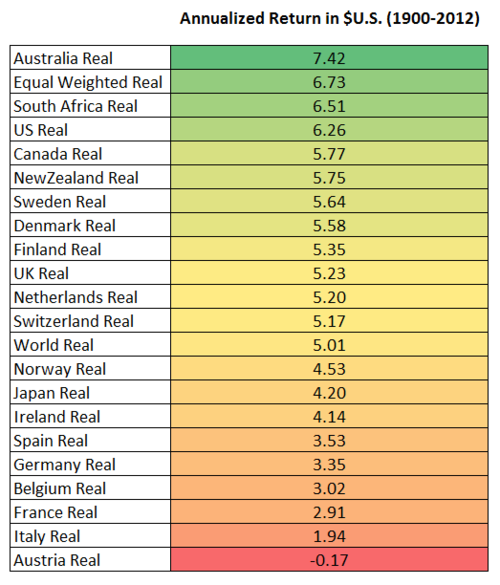

Triumph of the Optimists

Dimson, Marsh and Staunton’s book Triumph of the Optimists is a must-read for many reasons, but the core message (hinted at in the title) is that equity markets across the 20 major countries that the authors studied have performed well since 1900 —19 have delivered positive returns after inflation. At the right is a table of the annualized returns for these 20 countries between 1900 and 2012 (note: 2013 data not yet available, so these numbers would all get better, sometimes much better). The U.S. market has been one of the top performing markets over the past 113 years. It lagged Australia and South Africa, but because it was many times the size of those smaller markets, its performance has been amazing. It is interesting to note that the top markets are very rich in natural resources.

Worst Case Scenarios

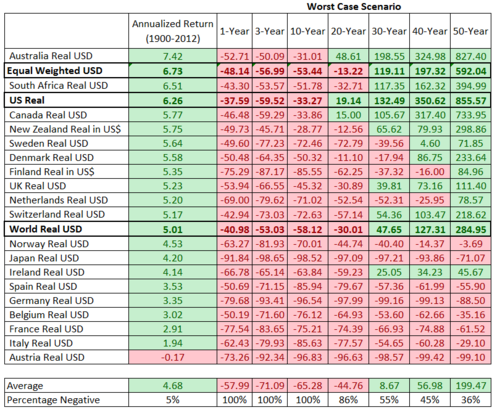

While the long term record has been strong for equities, nobody has a 113 year time horizon (well, unless you are Ray Kurzweil). Investors are still jittery today and worried about the risk in stocks, so I ran the worst-case scenarios for all 20 equity markets over a variety of different holding periods, which are listed in the table below (these returns are in US dollars, so they represent the returns that a U.S. investor would earn rather than a local investor in each respective market—the local returns are quite similar).

While the U.S. has never had a negative 20-year period of returns, most markets have. Other than the U.S., only the Canadian and Australian markets have provided positive returns in all 20-year periods. Because the U.S. has such a dominant weight in the World portfolio, I’ve also included an equal weight portfolio here, which does very well (equal weight to each of the 20 countries, rebalanced annually).

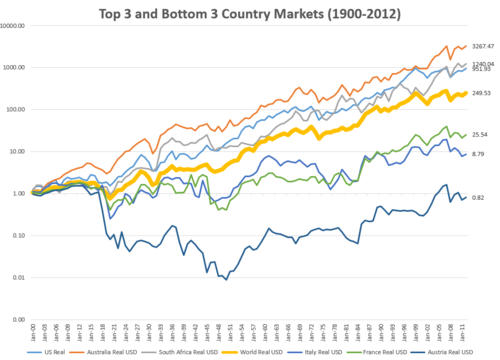

Here is the cumulative growth of the three best markets alongside the three worst and the world portfolio since 1900.

World War II

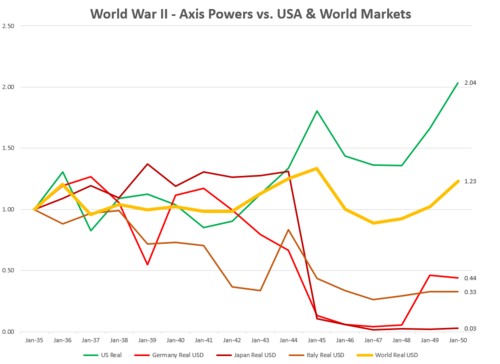

You’ll notice in the table above that many of the countries that have had very bad 40+ year worst-case scenarios were in the thick of things during World War II. Along with the Great Depression, World War II was the most disruptive influence on stock market returns. Below are the results for the U.S. and Axis powers in and around the war. As always, to the victor go the spoils. Germany’s stock market was essentially “reset” after the wind down of its three major banks (that had sympathized with the Nazis) in 1948, so German investors were wiped out.

The worst case scenario for us in the future would be some similar dislocation that crushed the U.S. equity market. It is interesting to note how the world portfolio performed (because it included both the winners and the losers—again this is in US Dollars but local version is similar). Of course, it would have been very hard (or impossible) to own a global portfolio in the 1940’s, but today it’s easy.

Go Global

Overcoming portfolio patriotism is important if you want to reduce long-term risk in your portfolio. The U.S. market has indeed had a remarkable multi-century run, and some of that success may be because America is “exceptional” in some key ways (then again, the insane American demographic explosion didn’t hurt, but that effect has stabilized—with a fertility rate of 1.9 we aren’t quite replacing our population). Still, other great countries have faltered in the past.

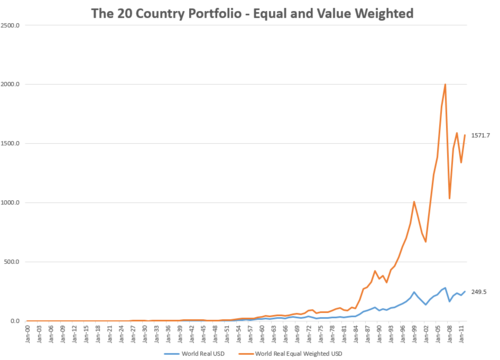

It just so happens that today, international country stock markets offer many of the best opportunities. As has been exhaustively demonstrated by many valuation experts (Grantham, Shiller, Meb Faber, and so on), the U.S. market is more expensive on an absolute and relative basis that most other major countries throughout the world. This isn’t a death sentence for the U.S. market, as there have been many examples where the market did quite well even from an expensive starting point. But it would be foolish, given how easy and cheap it is to buy global stocks, to keep your equity risk concentrated in your home country. This final chart is the Triumph of the Optimists writ large: it tracks the long term growth of $1 in the world equity portfolio (weighted by market cap) and an equal weighted version of the world portfolio. These returns include two World Wars, the Great Depression, countless recessions, crises, and market collapses. If you are an investor with a long time horizon, the global stock market should be the central part of your portfolio.

[i] https://advisors.vanguard.com/iwe/pdf/ICRRHB.pdf?cbdForceDomain=true