by Ben Carlson, A Wealth of Common Sense

“What goes up comes down, and what goes down comes back up.” – Mark Mobius

Emerging market stocks were one of the big relative underperformers in 2013. They were down around 3% for the year, but on a relative basis that number looks even worse against the 30%+ rise in U.S. markets and 20%+ increase in developed foreign stocks.

From the beginning of November 2013 to the end of January 2014, emerging markets fell over 9%. Unfortunately for many investors this led to the untimely capitulation selling that you tend to see after losses have occurred. Here are the details from Bloomberg:

Investors withdrew $4.5 billion from [emerging market] funds in the week through Feb. 12, extending the total outflow this year to $29.7 billion, according to Barclays Plc, which cited data provider EPFR Global. In 2013, a total of $29.2 billion left funds investing in emerging-market assets.

And right on cue after that large outflow of capital the inevitable rally ensued to the tune of a gain of over 13% from February to the end of June. It’s a shame that it has to be this way, but for every investor that wins there has to be someone on the other side that loses.

Emerging market economies go through more boom-bust cycles than the developed world so the stocks can be extremely volatile, fluctuating roughly twice as much as the S&P 500. So it makes sense to view the periodic losses from a historical perspective.

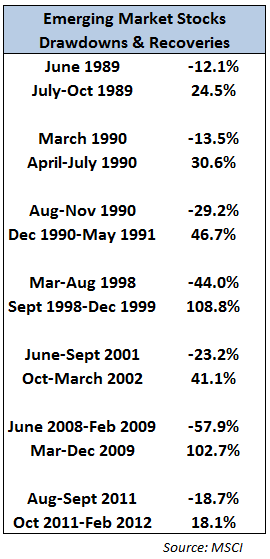

When investors think about volatility they usually focus on losses, but it works in both directions. Here are some of the sharpest declines in emerging market stocks over the years along with the corresponding recoveries:

It’s not necessarily the magnitude of the rallies that matters here because it takes a gain of 100% to break even on a 50% loss. It’s that selling after you have experienced large losses, which is exactly what many investors did in February of this year, is a terrible strategy for long-term investors.

Losses are a constant in the markets and they can be painful from a psychological standpoint because of our aversion to losing money. But poor returns become magnified when you sell after the fact and miss out on the subsequent recovery. It’s basically a double whammy of losses and opportunity costs.

Some investors can’t handle the volatility in EM stocks and that’s fine. But for those investors that have a long enough time horizon, with a willingness to withstand occasional losses and are investing on a consistent basis these more volatile markets actually work in your favor because you have more opportunities to buy in at lower prices.

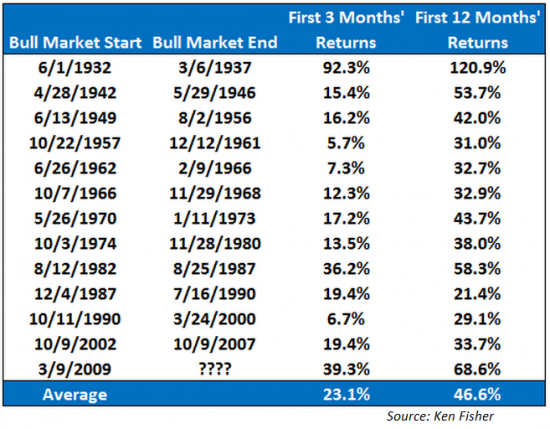

Also, emerging markets aren’t the only stocks that have shown quick snapback rallies in the past. Here are the initial rallies over the first 3 and 12 months of the biggest bull markets in the S&P 500 going back to the 1930s:

It may not seem like it with stocks at all-time highs but stocks will fall again in the future. I have no idea when that will happen but it will.

Try to remember that stocks can fall very quickly but rise just as fast so you don’t get whipsawed by magnifying the downturns through bad behavior.

Source:

Emerging market funds outflow surpass total 2013 sales (Bloomberg)

Further Reading:

Putting emerging market stock losses into perspective

Subscribe to receive email updates and my monthly newsletter by clicking here.

Follow me on Twitter: @awealthofcs

Copyright © A Wealth of Common Sense