by William Smead, Smead Capital Management

At Smead Capital Management we are conscious of the few, but significant pitfalls which we believe exist for the long-duration common stock investor. One of the main pitfalls we want to avoid is the over-capitalization curse. This is a situation where investor enthusiasm gets very high, prices get historically high and investors drown the company, industry or sector with capital. In our experience, it pays to avoid the over-capitalized areas for as long as five to ten years as they work their way back to being hated and contentious.

We were recently reminded of this pitfall by Wall Street Journal Writer, Andrew Blackman, who wrote a piece called, “Private Equity Has More Than It Can Spend.” Here is how he explains the over-capitalization of the private equity sector:

It [the private equity industry] has been so successful in raising money from investors recently that it can’t spend it fast enough. The amount of money raised by private-equity firms but not yet invested—known as dry powder—hit a record high of $1.073 trillion globally at the end of 2013, according to data provider Preqin, an increase of $130 billion from 2012. The total has continued to grow this year, reaching $1.141 trillion globally as of the start of June.

Some background for our new readers might be necessary. Thirty years ago there was a small segment of money managers called leveraged-buy-out or LBO firms. This was a group of people who looked to buy publicly-traded companies with borrowed money. In the 1980’s, much of that borrowed money came from junk-bond financing by my original firm, Drexel Burnham Lambert. A market for the trading and issuance of junk-bonds was created and run by the junk bond king, Michael Milken. Public companies that were targets of the buyouts had to be very depressed in price to justify the double-digit interest rates paid by LBO firms in the 1980s and 1990s. I remember in those days that large institutional investors and white-shoe investment firms did not want to be affiliated with what was considered unsavory borrowing and speculation.

When the largest investors in the world, US institutional investors, go from not being involved in an arena to having as much as 20% of their portfolios invested in a 25-year stretch, the possibility of over-capitalization exists. In explaining Harvard’s commitment to private equity investments equal to 16% of their endowment and 5% more than in US long-only equities, former CIO Jane Mendillo said the following in Barron’s on February 8th, 2014:

You’ve talked about some of the challenges now in the private-equity industry.

Private equity is a much more crowded place than it was 10 or 20 years ago. So you need to be choosy and pick the right managers and opportunities. It has been estimated there is a trillion dollars of dry powder in the private-equity industry today.So that’s money committed by investors, waiting to be deployed?

That’s right. That is going to create a competitive environment for private-equity managers who are putting money to work. It will drive up deal prices and drive down returns to more modest levels.

Let us say what we think nobody in the private equity arena wants said: we believe that over-capitalized market returns won’t just moderate, they will become miserable. Experience has taught us that those who believe their superior money management firm in a field is going to be the freak winner in an outgoing tide are dreaming. Remember those who bought Cisco and Microsoft in 1999 as the “pickaxe” companies? They weren’t direct dotcom companies and investors felt they could participate in the growth of the Internet through them without getting burned when the bubble burst.

Not only did these “pickaxe” stocks lose a great deal of money from 2000-2002, but they have never made it back to the price they were at their peak 14 years ago. They were a part of a massive over-capitalization, a curse, with unbelievable investors’ enthusiasm, high prices and too much capital. Secondly, most major tech companies of any kind became large-cap companies by 1999, and the large-cap growth and core categories drowned in capital as a result of the way large-cap indexes were overwhelmed. This spread the over-capitalization curse to most of the large-cap sector because managers either adapted in the late 1990s towards owning some, or saw their asset base shrink through redemptions.

The problem with private equity—from our perspective— is not just that it could do very poorly from this over-capitalization, but it might have caused a large misallocation in less esoteric common stock investing. We think massive money in the hands of LBO firms has had a huge impact on the outperformance we’ve seen the last 14 years in small and mid-cap stock indexes in the US relative to large-cap US long-only investments.

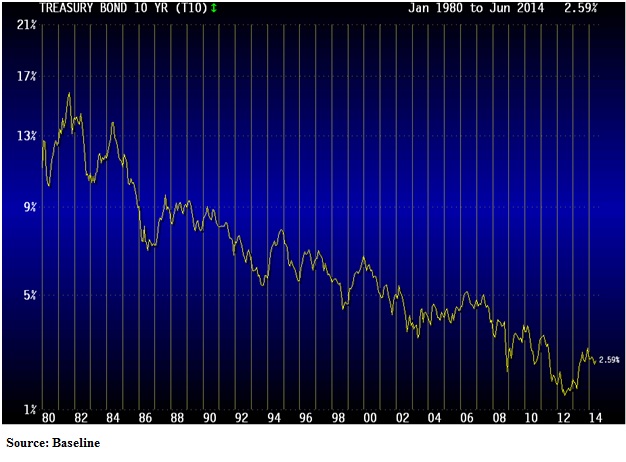

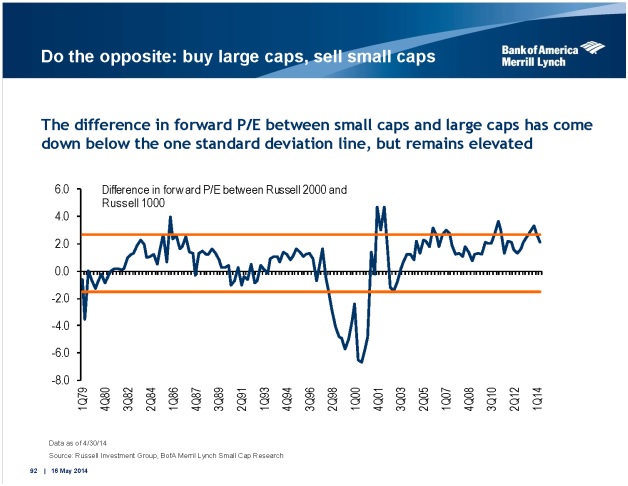

Professor Eugene Fama won the Nobel Prize for Economics last year. Some of his more notable work showed that small capitalization could be a factor generating alpha for investors over long time periods. Is it possible Fama and his theory have gained adulation as an accidental byproduct of a once in a lifetime movement into an esoteric asset class? Has his theory been massively dependent on cheap money propagated by the tech bubble recession and the effort by the Federal Reserve to counter the 2007-09 financial meltdown? Below is a chart showing the 30-year decline in US interest rates and how expensive small-cap US long only-equity is in relation to its somewhat larger brethren as represented by the Russell 2000 Index (small-cap) and the larger Russell 1000 Index.

If you compare the Russell 2000 to the S&P 500 Index, as we do below, from the beginning of 2000 to today, it is easy to see how much the move into private equity might have affected asset class returns and the attitudes of those practicing asset allocation.

Writing on June 23, 2014 for the Wall Street Journal, Gregory Zuckerman noted that institutions such as endowments and pension funds missed out on the stock rally entirely at the expense of adding alternative investments such as hedge funds and private-equity funds to their portfolio. Here’s what Zuckerman learned from one of the institutional participants:

Those shifting to alternative investments more recently could be “too late to the game,” said Scott Malpass, chief investment officer at the University of Notre Dame, which has had more than 50% of its $9.2 billion endowment in alternative investments for more than a decade.

Betting on hedge funds and private equity “can be a knee-jerk reaction to the crisis,” he said.

As with prior over-capitalization curses, we don’t know how this one will get rectified. We do have great confidence in avoiding both the asset class involved and any other asset class that has been involuntarily distorted.

Warm Regards,

William Smead

The information contained in this missive represents SCM’s opinions, and should not be construed as personalized or individualized investment advice. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It should not be assumed that investing in any securities mentioned above will or will not be profitable. A list of all recommendations made by Smead Capital Management within the past twelve month period is available upon request.

This Missive and others are available at smeadcap.com

Copyright © Smead Capital Management