by R.P. Seawright, Above the Market

I occasionally write for outside publications. When those publications are digital iterations of traditional media outlets, their editors tend to be especially vigilant about keeping posts to 400-600 words (as compared with my 4,000 word monstrosity at The Big Picture today). That’s because their research says that few readers will go beyond that length, no matter how good the content (which is a real problem for me since I tend to favor and write long and fairly involved pieces). Accordingly, information can readily be provided. But meaning, which takes careful sifting and evaluation of evidence, must remain rare indeed.

For example, various governmental agencies regularly release trade balance data, information that routinely makes the news and engenders both comment and controversy. The data seems straightforward enough. However, Zachary Karabell‘s new book, The Leading Indicators: A Short History of the Numbers That Rule Our World, uses the example of the iPhone to explain why the data itself is not as useful and probative on its face as we’d like to think. With an iPhone’s component parts coming from at least 12 different countries and final assembly taking place in China, assigning value to various countries for trade balance analysis requires a careful parsing of the data. Yet the official trade balance figures follow specific international “rules of origin” protocols that assign fully $275 in value per phone to China even though only about $10 of true value per phone is provided there.

Thus the stardard issue trade balance numbers may mean a lot less than we’re prone to think. Accordingly, if such data is going to be substantively useful and meaningful (at least for more than an extremely rough outline), more than 600 words of analysis are going to be needed.

That said, the 600 word barrier itself may well be wildly optimistic. A survey by the American Press Institute found that roughly six in 10 Americans acknowledge that they do nothing more than read news headlines to get “news.” They can’t even be bothered with a measly 600 words (which most readers can complete in less than 3 minutes; this article comes in at 750 words by the way).

Even worse, our failure to read beyond the headlines doesn’t stop us from sharing and commenting on the information we didn’t read. NPR’s April Fools’ Day joke/story entitled Why Doesn’t America Read Anymore?, the link to which isn’t a story at all, but rather a commentary about some people’s propensity to share and opine on NPR stories that they haven’t actually read. The story went viral when pranksters in on the joke linked to the piece and others then argued that they do too read and indignantly shared the link with exhortations to “Read the story!” without actually having clicked on it (if they had they obviously would have realized that the whole thing was a prank).

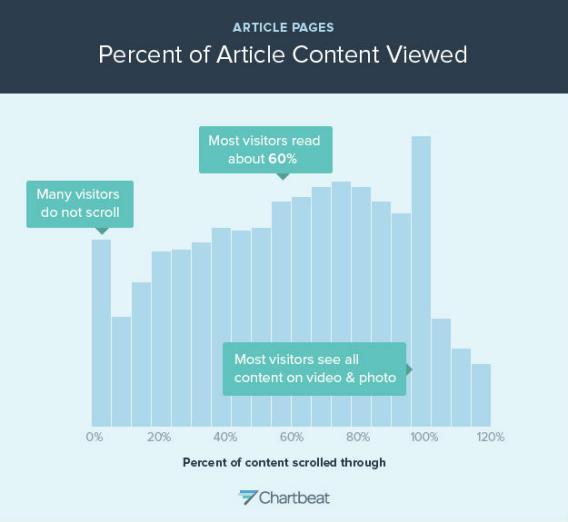

Some commenters are at least honest enough (if still irony-challenged) to start their social media shares with “TL;DR” — short for Too Long; Didn’t Read. But they then proceed often to offer an opinion on the shared article anyway. As Tony Haile, the chief executive of the web traffic analytics company Chartbeat, recently put it (on Twitter, naturally): “We’ve found effectively no correlation between social shares and people actually reading.” According to Chartbeat’s Josh Schwartz, “When people land on a story, they very rarely make it all the way down the page. A lot of people don’t even make it halfway” (see below).

Few people are reading all the way to the end of this or any other internet article and a surprisingly big number aren’t reading at all. Moreover, articles that get a lot of social media shares don’t necessarily get read very deeply and articles that get read deeply aren’t necessarily generating lots of shares. If the most meagre bits of information aren’t fully or adequately digested, true meaning becomes even rarer and more valuable.

I repeat it often and in a variety of forms and contexts. Information is cheap but meaning is expensive. The concept is on my masthead above. In this data-soaked age, it’s easy to claim that “[d]ata has become our currency.” But if we’re to avoid huge personal and professional understanding deficits, we need to recognize that our most valuable stock-in-trade isn’t the data itself, easy though it is both to obtain and to misunderstand. Our currency should be and our edge should reside in being able to ascertain what these enormous piles of data actually mean. Such meaning is expensive and getting more so by the minute.

Copyright © Above the Market