by Kathy Jones, Vice President, Fixed Income Strategist, Schwab Center for Financial Research

Key Points

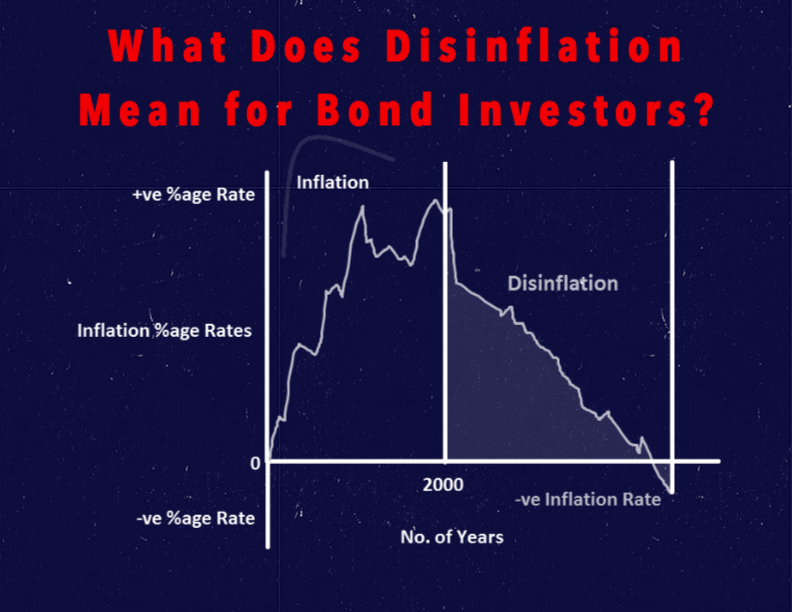

- With slow global economic growth, market sentiment has shifted from concerns about inflation to worries about disinflation or deflation.

- Until growth picks up, the bond market will likely continue to face low long-term yields and flattening yield curves.

- Bond investors may need to lower their expectations for long-term bond yields and consider new strategies for dealing with shifting markets.

With slow global economic growth, market sentiment has shifted from concerns about inflation to worries about disinflation or deflation, meaning either a falling inflation rate or a decline in prices. As a result, until growth picks up we'll likely continue to face low long-term yields and flattening yield curves in the bond market.

Let’s face it, for most people bond investing is not the most exciting topic. But lately, it has seemed even less exciting than usual. Ten-year Treasury yields have been locked in a narrow 2.6% to 2.8% range since the beginning of the year. Yield spreads between corporate bonds and Treasury bonds of comparable maturity are grinding lower at a pace of a few basis points a week. Similarly, the yield ratio of muni bonds over Treasuries has been holding in a range. And compared to the stock trading, bond trading is about as low frequency as you can get.

But there has been some action of note lately; it has just been hard to spot. In the major developed bond markets, the dominant trend has been the flattening of yield curves. Long-term bond yields have been trending lower, narrowing the spread between short-term rates and long-term rates. It's especially notable since most central banks are holding short-term rates near zero to try to boost economic growth. Yet, flattening yield curves are usually associated with expectations of slowing growth and low inflation. The implications are that bond investors may need to lower their expectations for long-term bond yields and consider new strategies for dealing with shifting markets.

Inflation has flattened out

How times have changed. At the spring International Monetary Fund (IMF) meeting in Washington D.C., finance officials from around the world expressed concern about falling inflation. Yet, as recently as a year ago, central bankers were being criticized for pursuing loose monetary policies that would trigger inflation. And over the course of the past forty years or so, central banks—with the exception of Japan—have focused almost entirely on fighting inflation, not promoting it. But now the major worry is disinflation or deflation—or the newly minted term "lowflation."

Deflation is a sustained fall in the general price level of goods and services, while disinflation occurs when the inflation rate is positive but declining. Lowflation refers to an inflation level that's consistently lower than the rate targeted by monetary policymakers.

Inflation in developed countries is edging lower

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Consumer Price Index: Harmonized Prices: Total All Items for the Euro Area, Total All Items Urban Consumers, Total All Items for Japan, Total All Items for China, Percent Change from Year Ago, monthly data as of February 2014.

Behind the concern is that low inflation in the world's largest economies is a sign of weak global demand. While the prospect of falling prices may seem like a good thing to most of us, deflation often means consumers postpone purchases because they expect prices to be lower in the future. Weak consumption and declining prices often lead businesses to reduce investment, further slowing economic growth. It can also make it more difficult for governments, businesses and individuals to pay down debt. Finally, as Japan has learned over the past decade, once deflation takes hold, reversing it is easier said than done.

Some members of the Federal Reserve, including Fed Chairwoman Janet Yellen, have recently expressed concerns that inflation is running at about half of its 2% target level. But the Fed's forecasts still call for inflation to rise to 2% in the longer-term and the Fed appears to be committed to exiting its expansive monetary policy and moving toward higher short-term interest rates sometime in 2015.

Yet, since the beginning of the year, 30-year Treasury yields have fallen by 49 basis points while two-year yields have only dropped by about three basis points. That's a big move toward a flatter yield curve in a short period of time. The market seems to be signaling concern about a premature hike in rates occurring at a time of slow growth and low inflation.

Since the end of the recession, real gross domestic product (GDP) growth in the U.S. has averaged only 2.3%, compared to 3.3% for the prior 10 years. Despite interest rates at near zero and several rounds of bond buying meant to stimulate growth, the economy's pace remains far from robust. With the prospect of tighter monetary policy on the horizon, the message from the market is one of subdued expectations.

Since the end of 2013, longer-term Treasury yields have fallen more than shorter-term yields.

Source: Bloomberg. U.S. Treasury Actives Curve. Bars represent the change in yield, in basis points, from December 31, 2013 to April 11, 2014.

Worries over lowflation are even more pronounced in Europe and Japan. Europe's inflation rate fell to 0.5% in March and has been trending lower for over a year. Moreover, some of the countries within the European Union have experienced deflation since the onset of the financial crisis. The European Central Bank (ECB) has been reluctant to embrace more aggressive monetary policy stimulus, believing that the decline in the economies of the highly indebted southern European countries is an outgrowth of structural reforms needed to make those economies more competitive.

As long as deflation was contained to the peripheral countries, it was not a concern. But recent low inflation in the core countries—like Germany and France—has raised the specter of deflation spreading from the periphery to the core. And while ECB President Draghi has talked a good game about expanding monetary policy with his pledge to do "whatever it takes," very little has actually been done.

Recent strength in the euro against other major currencies is compounding the declining inflation trend and has encouraged investors to pile into the riskier bond markets of the peripheral countries. Even Greece, which had to restructure its debt just two years ago, has been able to return to the market at very low yields. Concerns about low inflation may cause the ECB to take further action down the road, but for now Europe appears uncomfortably close to the tipping point of deflation.

European bonds yields continue to fall

Source: Bloomberg, as of April 11, 2014. Italy Generic Govt 10 Year Yield (GBTBGR10), Spain Generic Govt 10 Year Yield (GSPG10YR), France Generic Govt 10 Year Yield), Portugal Generic Govt 10 Year Yield (GSPT10YR), and Greece Generic Govt 10 Year Acting as Benchmark (GGGB10YR).

In Japan, inflation has picked up slightly over the past year as a result of Japan's adoption of aggressive monetary policy, known as "Abenomics." But the effects already seem to be waning, as economic growth has softened due to the recent tax hike. And the most recent comments from the Bank of Japan suggest it will take no new action to expand monetary policy. With more than a decade of deflation already, an aging and shrinking labor force and one of the highest debt/GDP ratios in the developed world, Japan doesn't have a lot of room to maneuver. Even China has seen a decline in inflation as a result of its slowing economy.

So while the markets signal concerns about soft growth and declining inflation globally, there doesn't appear to be much on the horizon to reverse the trend in the near term. Until economic growth shows signs of picking up globally, lowflation is likely to mean bond yields stay low and yield curves will continue to flatten.

What to do?

So what's a bond investor to do? Long-term rates appear to be range-bound at low levels and short-term rates are likely to move higher eventually, since throughout much of the world there is little room for short-term rates to move lower. And yields aren't attractive on either end of the yield curve.

In the U.S., short-to-intermediate term yields are starting to move higher in anticipation of Fed tightening next year. Any signs of life in the economy would probably mean price declines for bonds with maturities of three years and under—the very part of the market where many investors have fled for safety.

One alternative for investors who try to take a tactical approach to the duration of their portfolios is a barbell strategy. A barbell strategy involves weighting the maturities of bonds in a portfolio at the short and long ends of the spectrum, avoiding the intermediate maturities. It's far from a perfect solution, since yields are still low across the curve and a rise in rates could have a negative impact on the overall portfolio.

But it can help avoid some of the potential losses in the short-to-intermediate sector of the yield curve if rates rise faster for shorter maturity bonds than longer maturity bonds. You can still achieve an average duration in the intermediate term while not necessarily having as much exposure to the potential volatility in that part of the yield curve.

For long-term investors who don't take a tactical approach to duration, a laddered approach—spreading out maturities evenly—can still work, but you may want to consider moving the average duration out a bit longer on the expectation that future rate increases will not be as great for long-term yields as short-term yields. However, since longer term bonds are more sensitive to interest rate changes, the overall portfolio would still be susceptible to volatility if interest rates move up.

What not to do: Chase yield

One of the strategies to avoid is yield chasing by investing in riskier segments of the bond market. It's never a great idea in my view, but in a world where the yield curve is flattening it can be especially risky. Valuations for some of the riskier sectors of the market, such as high-yield bonds and peripheral European bonds, are stretched by historical standards, reflecting the demand for yield. As 2015 and the prospect of a U.S. rate hike get closer, some shakeout is likely.

Even though it seems unlikely that short-term rates will be moving up quickly, just the indication that they're going to be "unanchored" from zero down the road could cause the yield chasers to run for cover. It's probably best to avoid being caught in the crowd. That's the kind of excitement in the bond market that we like to avoid.

I hope this enhanced your understanding of disinflation. I welcome your feedback—clicking on the thumbs up or thumbs down icons at the bottom of the page will allow you to contribute your thoughts.

Copyright © Scwhab.com