by Robert Seawright, Above the Market

The financial crisis (circa 2008-2009) brought out discussions about “lost decades” in the investment markets, 10-year periods that suffered negative equity returns. It even prodded PIMCO to argue that the investment universe had fundamentally changed, that an “old normal” had been overtaken by a “new normal” characterized by persistently slow economic growth, high unemployment, significant geopolitical tension with social inequality and strife, high government debt and, of course, lower expected returns in the equity markets.

A Journal of Financial Perspectives paper from last summer considers how unusual it really is for equity markets actually to “lose a decade.” As it turns out, lost decades of this sort are not the exceptional episodes that only very rarely interrupt normal steady economic growth and progress that so many seem to think.

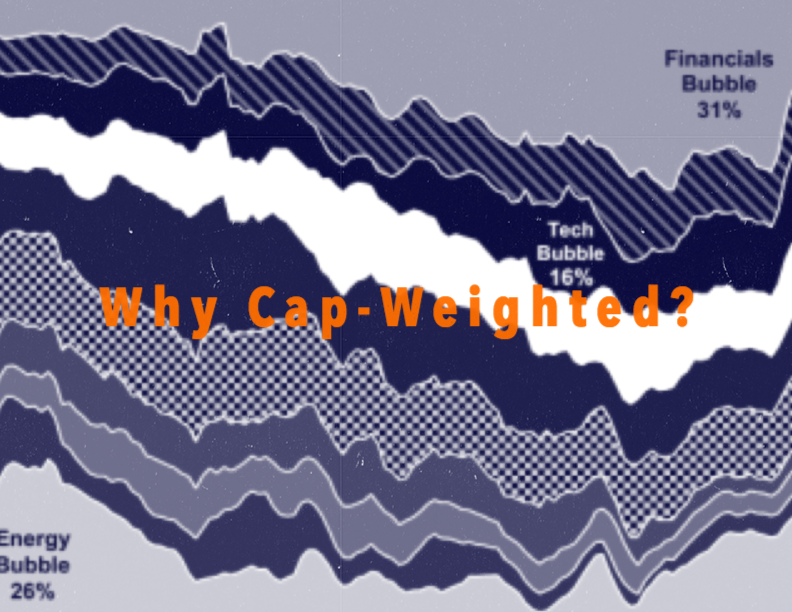

In the paper, Brandeis economist Blake LeBaron finds that the likelihood of a lost decade — as assessed by the historical data for U.S. markets via a diversified portfolio — is actually around 7 percent (in other words, about 1 in 14). Adjusting for inflation (using real rather than nominal return data) makes the probability significantly higher (more like 12 percent, nearly 1 in 8). The chart below (from the paper) shows the calculated return (nominal in yellow, real in dashed) for ten-year periods over the past 200+ years, and shows six periods in which the real return dips into negative numbers.

So a “lost decade” actually happens fairly frequently. As LeBaron summarizes:

The simple message here is that stock markets are volatile. Even in the long-run volatility is still important. These results emphasize that 10-year periods where an equity portfolio loses value in either real or nominal terms should be an event on which investors put some weight when making their investment decisions.

The key practical take-away is that those within 5-10 years of retirement (in either direction) who are taking or planning to take retirement income from an investment portfolio should consider hedging their portfolios so as to avoid sequence risk. Losses close to retirement have a dramatically disproportionate impact on retirement income portfolios. As so often happens, the risks are greater than we tend to appreciate.

Copyright © Above the Market