Five Stinkin’ Feet

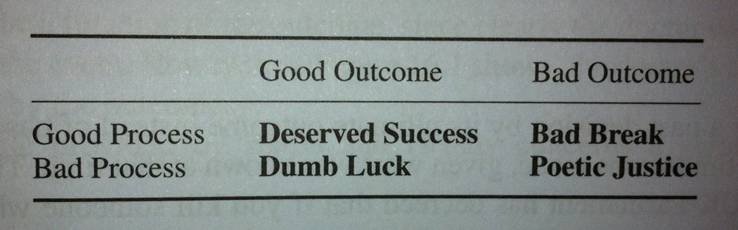

Investment Belief #5: Process Should Be Prioritized Over Outcomes

by Robert P. Seawright, Above the Market

My first baseball memory is from October 16, 1962, the day after my sixth birthday, by which time I was already hooked on what was then the National Pastime. In those days, all World Series games were played during the day. So I hurried home from school on that Tuesday afternoon to turn on the (black-and-white) television and catch what I could of the seventh and deciding game of a great Series at the then-new Candlestick Park in San Francisco between the Giants and the New York Yankees.

Game seven matched New York’s 23-game winner, Ralph Terry (who in 1960 had given up perhaps the most famous home run in World Series history to lose the climatic seventh game), against San Francisco’s 24-game-winner, Jack Sanford. Sanford had pitched a three-hit shutout against Terry in game two, winning 2-0, while Terry had returned the favor in game five, defeating Sanford in a 5-3, complete game win. Game seven was brilliantly pitched on both sides. While Terry carried a perfect game into the sixth inning (broken up by Sanford) and a two-hit shutout into the ninth, Sanford was almost as good. The Yankees pushed their only run across in the fifth on singles by Bill “Moose” Skowron and Clete Boyer, a walk to Terry and a double-play grounder by Tony Kubek.

When Terry took the mound for the bottom of the ninth, clutching to that 1-0 lead (the idea of a “closer” had not been concocted yet), he faced pinch-hitter Matty Alou, who drag-bunted his way aboard. His brother Felipe Alou and Chuck Hiller struck out, bringing the great future Hall-of-Famer Willie Mays to the plate, who had led the National League in batting, runs and homers that year, as the Giants’ sought desperately to stay alive. Mays doubled to right, but Roger Maris (who had famously hit 61 homers the year before and who was a better fielder than is commonly assumed) cut the ball off at the line. His quick throw to Bobby Richardson and Richardson’s relay home forced Alou to hold at third base.

When Terry took the mound for the bottom of the ninth, clutching to that 1-0 lead (the idea of a “closer” had not been concocted yet), he faced pinch-hitter Matty Alou, who drag-bunted his way aboard. His brother Felipe Alou and Chuck Hiller struck out, bringing the great future Hall-of-Famer Willie Mays to the plate, who had led the National League in batting, runs and homers that year, as the Giants’ sought desperately to stay alive. Mays doubled to right, but Roger Maris (who had famously hit 61 homers the year before and who was a better fielder than is commonly assumed) cut the ball off at the line. His quick throw to Bobby Richardson and Richardson’s relay home forced Alou to hold at third base.

With first base open, Giants cleanup hitter and future Hall-of-Famer Willie McCovey stepped into the batter’s box while another future Hall-of-Famer, Orlando Cepeda, waited on deck. Yankees Manager Ralph Houk decided to let the right-handed Terry pitch to the left-handed-hitting McCovey, who had tripled in his previous at-bat and homered off Terry in game two, even though Cepeda was a right-handed hitter. With the count at one-and-one, McCovey got an inside fastball and rifled a blistering shot toward right field but low and just a step to Richardson’s left. The second baseman, who Terry had thought was out of position, snagged it and the Series was over. McCovey would later say that it was among the hardest balls he ever hit.

“It was an instant thing, a bam-bam type of play,” recalled Tom Haller, who caught the game for the Giants. “A bunch of us jumped up like, ‘There it is,’ then sat down because it was over.

“It was one of those split-second things. ‘Yeah! No!’ “

Hall-of-Famer Yogi Berra, who has pretty much seen it all, said, “When McCovey hit the ball, it lifted me right out of my shoes. I never saw a last game of a World Series more exciting.”

Had McCovey’s frozen rope been hit just a bit higher or just a bit to either side, the Giants would have been crowned champions. As recounted by Henry Schulman in the San Francisco Chronicle, it was a matter of “[f]ive stinkin’ feet.”

Tremendous skill was exhibited by the players on that October afternoon over half a century ago. But the game – and ultimately the World Series championship – was decided by a bit of luck: that “five stinkin’ feet.”

It’s Best to Be Lucky *and* Good

We all know that the outcomes in many activities in life combine both skill and luck. Baseball, like investing, is one of these. Understanding the relative contributions of luck and skill can help us assess past results and, more importantly, anticipate future results.

In Major League Baseball, over a 162-game season the best teams win roughly 60 percent of the time. The Giants won 101 games during the 1962 season (62 percent of the time) to win the National League pennant (plus two out of three additional play-off games against the Los Angeles Dodgers, with whom they had tied); the Yankees won 96 games (59 percent of the time) to top the American League. But over shorter stretches, it’s not unusual to see significant deviations from those percentages and noteworthy streaks.

Since mean reversion establishes that the expected value of the whole season is roughly 50:50 (or slightly above or below that level), 60 percent being great means that there is a lot of randomness in baseball. The very best teams still lose about four out of every ten games overall, to inferior teams. That idea makes intuitive sense – the difference between ball four and strike three can be tantalizingly small (even if and when the umpire gets the call right). So can the difference between a hit and an out, as the final play of the 1962 World Series bears witness.

Luck (randomness) is also a huge factor in investment returns, irrespective of manager. “Most of the annual variation in [one’s investment] performance is due to luck, not skill,” argues California Institute of Technology professor Bradford Cornell, in a view shared by all the experts (Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman talks about it in this video, for example). Not very many people made money in 2008, no matter how good they were, and nearly everybody made good money in 2013, no matter how lousy they were. Perhaps more troublesome is our perfectly human tendency (“self-serving bias“) to attribute poor results to bad luck but good results to skill.

The efficient markets hypothesis claims that all market outperformance is attributable to luck. However, it has been demonstrated, by statistical measures and common sense, that investment skill exists and matters. There is a wide gulf between saying investing is all luck and saying it has a lot of luck. But it is important to remember that, on the overall continuum, investing is closer to the luck side (which is why it is so difficult to profit all the time and to succeed when the market is tanking).

So what constitutes skill in a field where probabilities dominate? And how can we recognize it so we can make investment allocations wisely? We tend to focus on outcomes. But luck can overcome skill over long periods and be the deciding factor at key moments. Despite remarkably long odds, Richard Lustig has actually won the lottery seven different times, and it’s not because of skill. The key to improving our odds, then, is to focus on good investment process. A good process won’t always lead to a good outcome (Willie McCovey’s process and his implementation of that process were superb in our lead-off example – he crushed the ball yet he still made out), but it provides the best and most consistent opportunity to do so.

In all probabilistic fields, the best performers dwell on good process. This is true for great investors and great baseball players. A great hitter focuses upon a good approach, his mechanics, being selective and hitting the ball hard. If he does that – maintains a good process – he will make outs sometimes (even when he hits the ball hard, like Willie McCovey as the painful last out of the 1962 World Series), but overall the hits will take care of themselves. Maintaining good process is really hard to do psychologically, emotionally, and organizationally. But it is absolutely imperative for ongoing investment success.

As suggested above, a portfolio’s results are largely dictated by overall market performance during the applicable time period. Thus the more risk-averse strategies will generate better returns in a difficult market by protecting the downside and the reverse will also tend to be true, managers with higher risk tolerances will be more likely to succeed during periods of strong market returns. The conventional method of dealing with this dilemma is to “risk adjust” the results, comparing nominal returns with volatility, but this approach is uncertain at best in that volatility and risk are hardly the same thing.

Accordingly, the decision as to which managers and which funds deserve assets, as a practical matter, is often determined — surprise! — by performance data and how one does the analysis. With current five-year performance numbers now free of 2008, investors simply looking at performance over the past one, three and five-year periods for what’s hot will go with those managers who put pedal-to-the-metal. Before that, those same managers generally looked lousy on account of their 2008 numbers, providing support for the more risk-averse managers.

Whether one, three, five or longer-term performance numbers are ultimately deemed more instructive will largely be determined by what happens during the next couple of years or so. If markets are going to remain strong over the next two years, advisors that made performance-based decisions based upon the five-year numbers will look like geniuses. A major market downturn will make them look like morons. That’s why looking at outcomes can be so dangerous, especially since nobody has demonstrated that market timing can work consistently.

Everybody – advisors and clients alike – wants the same thing in the end: high relative returns with a minimum number of sleepless nights. Human psychology being what it is, however, investors are often their own worst enemies. Risk-averse investors, for instance, should want to underperform the benchmark in a bull market. It implies a strategy of risk management that will protect them when, inevitably, the market turns over. Of course the benchmark is going to outperform that strategy in a sustained bull market, as 2013 so aptly demonstrated. What tends to happen then is that investors, frustrated by trailing the index for a while, switch their money into more aggressive choices shortly before a downturn. That goes a long way toward explaining why most people and most managers generally underperform.

This “time slice” issue and behavioral economics makes the selection of investments and investment managers a tricky thing. You may choose not to care about any particular benchmark. You may develop and analyze future financial requirements and then tailor investment decisions to achieving those. What happens to the S&P 500 or other benchmark over some random period of time is then of merely passing interest. But that’s easier to do in theory than in practice. It remains a serious challenge for advisors to maintain trust and business during periods of extremes. We all want to win – all the time.

But as I have noted repeatedly, investing is a loser’s game (using the famous expression of Charley Ellis) much of the time – with outcomes dominated by luck rather than skill and high transaction costs. If we “play the odds” and if we avoid mistakes we will generally win. Those are the keys to good investment process.

Get a Good Pitch to Hit

In baseball, hitters looking to improve their odds are careful to get a good pitch to hit. Ted Williams was almost surely the greatest hitter of all-time. He was a two-time MVP, led the league in hitting six times and in home runs four times, and won the Triple Crown twice. A 19-time All-Star, he had a career batting average of .344 with 521 home runs, and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1966.

Williams was also the last player in Major League Baseball to hit over .400 in a single season (.406 in 1941). Ted’s career was twice interrupted by service as a U.S. Marine Corps fighter-bomber pilot. Had his career not been limited by his military service – especially since it was in his prime – Williams would likely have hit over 700 career home runs and challenged Babe Ruth’s famous record.

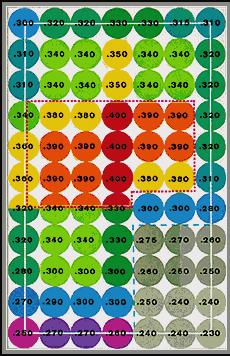

During spring training of his first professional season, Williams met Rogers Hornsby, who had hit over .400 three times and who was a coach for his AA team for the spring. Hornsby emphasized that Ted should always “get a good pitch to hit.” That concept became Williams’ “first rule of hitting” and the key to his famous and innovative hitting chart (shown right).

During spring training of his first professional season, Williams met Rogers Hornsby, who had hit over .400 three times and who was a coach for his AA team for the spring. Hornsby emphasized that Ted should always “get a good pitch to hit.” That concept became Williams’ “first rule of hitting” and the key to his famous and innovative hitting chart (shown right).

The concept is a straightforward one — it’s easier to hit a pitch that’s belt high and right down the middle than one at the knees and “on the black.” Investors should be mindful of this concept too and always seek a “good pitch to hit.”

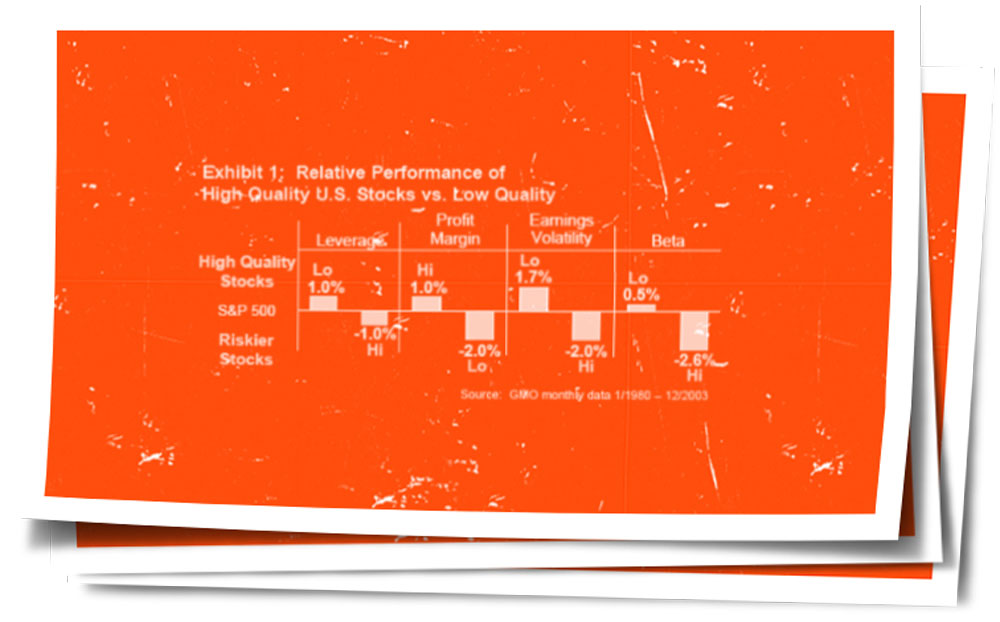

In part, getting a good pitch to hit means focusing on approaches and sectors that have the best opportunities for success. These include momentum investing (see here and here, for example), including highly quantitative (algorithmic) investing based upon momentum. Another area for potential outperformance is low beta/low volatility stocks. This surprising finding (since greater return is generally connected with greater risk) has been deemed to be the “greatest anomaly in finance.” Significantly, this approach works well in the large cap space, where closet indexers predominate. Moreover, despite rational “copycat risk” fears, there is good research providing reasons to think that this anomaly may well persist. Looking at this opportunity on a risk-adjusted basis only makes it more attractive.

The mid and small cap sectors provide more opportunities despite some liquidity constraints. International equities tend to provide the best opportunities due to the wide dispersion of returns across sectors, currencies and countries. Indeed, the SPIVA Scorecard demonstrates that a large percentage of international small-cap funds continue to outperform benchmarks, “suggesting that active management opportunities are still present in this space.” Moreover, managers running value strategies outperform and do so persistently, in multiple sectors, especially over longer time periods, although lengthy periods of underperformance must be expected and survived. In the current secular bear market I also encourage the use of portfolio hedging.

I wish to re-emphasize, however, that success in this arena is extremely hard to achieve and success achieved through good asset allocation can be given back quickly via poor active management. That is why I prefer an approach that mixes active and passive strategies and sets up a variety of quantitative and structural safeguards designed to protect against ongoing mistakes and our inherent irrationality. I want to be most active in and focus upon those areas where I am most likely to succeed. I also want to be careful to seek non-correlated asset classes (to the extent possible) in order to try to smooth returns over time and to mitigate drawdown risk.

For advisors, surviving in this business can be a major challenge. Succeeding by actually providing clients with real value is that much more difficult. It demands the bravery to incur much greater risk – but career and reputation risk rather than investment risk. For individuals, it requires the bravery to go against the crowd. Ultimately, investing is a zero sum game. In other words, all positive alpha is financed by negative alpha. It’s a mathematical certainty.

Value surely exists, but it can be very hard to find. In the equities markets I recommend starting by being very selective – getting a good pitch to hit. I suggest considering the use of active investment vehicles within portfolios for momentum strategies, focused (concentrated) investments, in the value and small cap sectors (domestic and international), for low volatility/low beta stocks, and for certain alternative investments. Passive strategies can be used to fill out the portfolio to provide further diversification. When you don’t have a good pitch to hit, don’t swing. When you do, hack away.

Not Screwing Up Trumps Good Choices

As noted, a good investment process is really difficult to achieve and even harder to sustain. The variables are many and the problems challenging. Charlie Munger borrowed a highly useful idea from the great 19th Century German mathematician Carl Jacobi that provides a helpful way to deal with the myriad problems investors face in trying to establish a good investment process.

Invert, always invert (“man muss immer umkehren”).

Jacobi believed that the solution for many difficult problems could be found if the problems were expressed in the inverse – by working backward. As in most investment matters, we would do well to emulate Charlie here.

During World War II, the Allied forces sent regular bombing missions into Germany. The lumbering aircraft sent on these raids – most often B-17 “Flying Fortresses” – were strategically crucial to the war effort and were often lost to enemy anti-aircraft fire. That was a huge problem, obviously.

During World War II, the Allied forces sent regular bombing missions into Germany. The lumbering aircraft sent on these raids – most often B-17 “Flying Fortresses” – were strategically crucial to the war effort and were often lost to enemy anti-aircraft fire. That was a huge problem, obviously.

One possible solution was to provide more reinforcement for the Fortresses, but armor is heavy and restricts aircraft performance even more. So extra plating could only go where the planes were most vulnerable. The problem of where to add armor was a difficult one because the data set was incomplete. There was no access to the planes that had been shot down, obviously. In 1943, the English Air Ministry examined the locations of the bullet holes on the returned aircraft and proposed adding armor to those areas that showed the most damage, all at the planes’ extremities.

The great mathematician Abraham Wald, who had fled Austria for the United States in 1938 to escape the Nazis, was put to work on the problem of estimating the survival probabilities of planes sustaining hits in various locations so that the added armor would be located most expeditiously. Wald came to a conclusion that was surprising and very different from that proposed by the Air Ministry. Since much of Wald’s analysis at the time was new – he didn’t have sufficient computing power to model results and didn’t have access to more recent statistical approaches – his work was ad hoc and his success was due to “the sheer power of his intuition.”

Wald began by drawing an outline of a plane and marking it where returning planes had been hit. There were lots of shots everywhere except in a few crucial areas, with more shots to the planes’ extremities than anywhere else. By inverting the problem – considering where the planes that didn’t return had been hit and what it would take to disable an aircraft rather than examining the data he had from the returning bombers – Wald came to his unique insight, later confirmed by remarkable (for the time, and long classified) mathematical analysis (more here). Much like Sherlock Holmes and the dog that didn’t bark, Wald’s remarkable intuitive leap came about due to what he didn’t see.

Wald realized that the holes from flak and bullets most often seen on the bombers that returned represented the areas where planes were best able to absorb damage and survive. Since the data showed that there were similar areas on each returning B-17 showing little or no damage from enemy fire, Wald concluded that those areas (around the main cockpit and the fuel tanks) were the truly vulnerable spots and that these were the areas that should be reinforced.

The more useful data was in the planes that were shot down and unavailable, not the ones that survived, and had to be “gathered” by induction in that instance. This insight lies behind what we now call survivorship bias – our tendency to include only successes in statistical analysis, skewing or even invalidating the results. Inverting the problem allowed Wald to come to the correct conclusion, saving many planes (and lives).

The key investment application (beyond the benefits of inverting the problems we face generally) is that in most cases we’d be better served by looking closely at the examples of people and portfolios that failed and why instead of the success stories, even though such examples are unlikely to give rise to book contracts with six-figure advances. Similarly, we’d be better served examining our personal investment failures than our successes. Instead of focusing on “why we made it,” we’d be better served by careful failure analysis and fault diagnosis. That’s where the best data is and where the best insight may be inferred. Besides, avoiding stupidity is usually easier than aspiring to brilliance.

If we avoid mistakes we will generally win. By examining failure more closely, we’ll have a better chance of doing precisely that. Basically, negative logic works better than positive logic. What we know not to be true is much more robust that what we know to be true. It’s like Michelangelo noted with respect to his master creation, the David. He always believed that David was within the marble he started with. He merely (which is not to say that it was anything like easy) had to chip away that which wasn’t David. “In every block of marble I see a statue as plain as though it stood before me, shaped and perfect in attitude and action. I have only to hew away the rough walls that imprison the lovely apparition to reveal it to the other eyes as mine see it.” By chipping away at what “didn’t work,” Michelangelo uncovered a masterpiece. There aren’t a lot of investment masterpieces, but by avoiding failure, we give ourselves the best chance of overall success.

“Bet” Whenever the Odds are Sufficiently in Your Favor

When I was a kid I had a paper route. One of my customers was a barber who made book on the side. Shocking, I know. The giveaway was the group of guys always hanging around but not getting their hair cut and the three telephones on the wall that rang a lot. Even as a kid I could tell that something was up.

Anyway, each week the barber and I had a wager. During the NFL season, I picked a winner of the Buffalo Bills game (the Bills were our local team) straight-up. When I was right, I got double the subscription price, before tip. When I was wrong, the barber got his paper free.

As it happened, I won a lot of the time – obviously aided by being able to decide which side of the bet I wanted, not having to worry about the spread and (in no small measure) by the Bills being pretty lousy during that period. One Monday after (yet another) win for me and loss for the Bills, I was feeling pretty haughty (imagine that) and started talking smack to the barber (imagine that). Finally, my exasperated barber told me something that made a big impression at the time and which resonates still, “Do it against the spread and then we’ll talk.”

Predicting which team will prevail in a football game and by what margin is a task of enormous complexity. The variables include numerical manifestations of individual athletic performances, coaching, weather, injuries and the random bounces of a fumbled oblong ball. As it turns out, almost nobody does that very well.

We are forward-looking creatures. We love to make forecasts, predictions and even wagers about the future. We just aren’t very good at it. But we sure do try.

Sports betting is obviously very big business. Nearly $120 million was bet legally on this year’s Super Bowl in Nevada alone (vastly more illegally, estimated to be in the hundreds of billions of dollars) and CBS reports that over $2.5 billion (with a “b”) is bet at Las Vegas sports books in a year. The sports books make money – a lot of money. But almost nobody else does, because winning in the aggregate is extremely difficult. In fact, about 97 percent of sports bettors lose money long-term.

One major exception to the general rule is the legendary gambler Billy Walters, a crucial member of the famous “computer group,” which used a careful and computerized process to make a fortune and, as a result, to revolutionize sports betting in the 1980s. Today, Walters uses multiple consultants – mostly mathematicians – just like a hedge fund manager uses analysts, and still makes a ton of money. Walters’s process is to create his own line largely using statistical measures of the teams and then to bet when his view of a game is significantly different from available commercial betting lines. He’s not opposed to trying to influence betting lines either. Walters has the power, the money and the reputation to bet on teams that he doesn’t actually favor in order to move the odds. Once that happens, he lays much larger bets on the other side, the side he wanted all along.

One major exception to the general rule is the legendary gambler Billy Walters, a crucial member of the famous “computer group,” which used a careful and computerized process to make a fortune and, as a result, to revolutionize sports betting in the 1980s. Today, Walters uses multiple consultants – mostly mathematicians – just like a hedge fund manager uses analysts, and still makes a ton of money. Walters’s process is to create his own line largely using statistical measures of the teams and then to bet when his view of a game is significantly different from available commercial betting lines. He’s not opposed to trying to influence betting lines either. Walters has the power, the money and the reputation to bet on teams that he doesn’t actually favor in order to move the odds. Once that happens, he lays much larger bets on the other side, the side he wanted all along.

Walters is staggeringly rich (according to 60 Minutes, he is “worth hundreds of millions of dollars”), but he claims a lifetime winning percentage of just 57 percent (a record that, over a single season, would put a bettor near the top of the toughest sports gambling contest in the world – for Walters to do that year after year is astonishing), as compared to a break-even of 52.38 percent (the winning percentage sports gamblers need to hit to offset paying out a 10 percent “vig” on their losing bets). Even so, while he has had losing months (as noted above, randomness can overcome a good process for substantial periods of time), he has never had a losing year during this 30-year streak.

But that winning streak only started after he made a major change in his approach. By his own account, Walters lost his shirt many times over before becoming focused, data-driven and careful to play the long game (making a profit while losing 43 percent of the time requires it, especially because the losing streaks can be very long indeed). One key is lots of bets – whenever the data suggests a significant edge – with bet size being determined by the extent of the edge. In Vegas parlance, Walters is a “grinder.”

Sports betting and trading the markets have a lot in common. The teams are commodities. The line is the price. Just like a trader, the gambler must judge whether a given price is correct based on future expectations. “Some traders can make money by figuring out [that] soybeans are undervalued or overvalued,” trader, sports gambler, and winner of this year’s ultimate sports betting competition, David Frohardt-Lane says. “The bettor’s skills are figuring out how good the teams are.” To win the SuperContest(and over half a million dollars), you needed to be more lucky than good, Frohardt-Lane insists. His take is that a 55 percent accuracy record over the long-term is about the best he can imagine being, so he had been extremely fortunate to nail 68 percent of his selections during the contest to win it. Thus Walters’ long-term 57 percent record is even more amazing. Oh, and after winning the big contest, Frohardt-Lane took the Broncos in the Super Bowl. Fed by rumor, speculation and greed, teams, like investments, can grow hot or cold for no good reason. Moving lines is remarkably similar to market bubbles. Walters insists that “[b]etting on a ball game is identical to betting on Wall Street.” Walters even claims that he has lost a lot of money in the markets and thinks the Wall Street “hustle” is far more dangerous than that in Las Vegas.

It should be no surprise then that many Wall Streeters have gambling histories, most prominently Ed Thorp. For more information, read Scott Patterson’s excellent book, The Quants. I even know a few (and maybe more).

I grew up in this business in the early 90s at what was then Merrill Lynch. My decade of legal work in and around the industry didn’t prepare me for big-time Wall Street trading. I’d ride the train to Hoboken early in the morning, hop on a ferry across the Hudson, walk straight into the World Financial Center, enter an elevator, and press 7. Once there, I’d walk into the fixed income trading floor, a ginormous open room, two stories high, with well over 500 seats and more than twice that number of computer terminals and telephones. When it was hopping, as it often was, especially after a big number release, it was a cacophonous center of (relatively) controlled hysteria.

It was a culture of trading, which makes sense since it was, after all, a trading floor. And it wasn’t all that different from a sports book. Most discussions, even trivial ones, had a trading context. One guy (and we were almost all guys) is a seller of a lunch suggestion. Another likes the fundamentals of the girl running the coffee cart. Bets were placed (of varying sorts) and fortunes were made and lost, even though customers did most of the losing because we were careful to take a spread (think “vig”) on every trade. The focus was always on what was rich and what was cheap and the what if possibilities of and from every significant event (e.g., earthquake in Russia – buy potato futures). The objective was always to make the most money possible, the sooner the better.

One of my colleagues there was an excellent mortgage trader who traced his success to his “training” as a gambler. While in college, in the days before the internet and relatively uniform betting lines, he created a remarkable betting process. He would find a group of games he wanted to play (via a system not nearly as sophisticated as the one Walters uses) and would then place bets with bookies in the cities of the teams playing. In each case he’d bet against the team located in the city of the applicable bookie. Because the locals disproportionately bet on the local team, the point spread would be skewed, sometimes by a lot. Thus he had an excellent true arbitrage situation with a chance to win both sides of the bet, which happened a lot. He traded mortgages in much the same way.

The take-away is thus straightforward (if not simple). “Play” whenever the odds are sufficiently in your favor. So many bets increase your odds of winning and diversifies your risk substantially.

Why We Screw Up

But why are successful investors, successful prognosticators and successful betters so rare? I have three reasons to suggest in addition to their implementing lousy processes. Indeed, these reasons are why their processes tend to be so lousy.

The first is our human foibles – the behavioral and cognitive biases that plague us so readily. These issues make us susceptible to craving the next shiny object that comes into view and our emotions make it hard for us to trade successfully and extremely difficult to invest successfully over the longer-term. Recency bias and confirmation bias – to name just two – conspire to inhibit our analysis and subdue investment performance. Roughly half of each year’s NFL play-off teams fail to make the play-offs the next season. Yet our predictions (and bets) disproportionately expect last year’s (or even last week’s) results to repeat. Another problem is herding. On average, bettors like to take favorites. Sports fans (and even analysts) also like “jumping on the bandwagon” and riding the coattails of perennial winners. Sports books can use these biases to shade their lines and increase their profit margins. So can the Street.

Experts are prone to the same weaknesses all of us are, of course. Philip Tetlock’s excellent Expert Political Judgment examines why experts are so often wrong in sometimes excruciating detail. Even worse, when wrong, experts are rarely held accountable and they rarely admit it. They insist that they were just off on timing (“I was right but early!”), or blindsided by an impossible-to-predict event, or almost right, or wrong for the right reasons. Tetlock even goes so far as to claim that the better known and more frequently quoted experts are, the less reliable their guesses about the future are likely to be (think Jim Cramer), largely due to overconfidence, another of our consistent problems.

We should never underestimate information asymmetry either. Information asymmetry is the edge that high frequency traders have and why Billy Walters focuses on player injuries and their impact in addition to his models. At a broader level, it’s why it’s so difficult to “beat the market.” Obviously, someone is on the other side of every trade. When you make a trade, what’s your edge vis-à-vis your counterparty?

The third reason is just plain luck. The world is wildly random. With so many variables, even the best process can be undermined at many points. Pundit Tracker describes the “fundamental attribution error,” the error we make when we overweight the role of the individual and underweight the roles of chance and context when trying to explain successes and failures.

Football fans will recall the controversial (to say the least) touchdown call that gave the Seattle Seahawks a 14-12 victory over the Green Bay Packers back in 2012. This play forced the NFL to settle the lock-out of its regular officials and thus get rid of the replacement officials. It was the play that looked like an interception to everyone but one of the (replacement) officials.

I am particularly struck by the huge impact this last-second turnaround had on gamblers. If Seattle’s desperation pass had correctly been ruled an interception, Green Bay – as 3½ point favorites — would have won by five, covering the spread. Instead, the replacement official’s call shifted the win from those who bet on the Packers to those who took the underdog Seahawks. Remarkably, that result meant that as much as $1 billion (that’s with a “b”) moved in one direction as opposed to the other.

Thus a clear win was eliminated due solely to the almost unbelievable incompetence of a single replacement official. That’s just dumb luck for bettors, and why it can be so frustratingly difficult to wager successfully on both our favorite teams and our favorite stocks. It may seem like the system is gamed, but investing successfully is just really hard (like gambling), as Tadas Viskanta so eloquently points out and I regularly reiterate.

In all probabilistic fields, like investing and gambling, the best performers dwell on process. A great hitter focuses upon a good approach, his mechanics, being selective and hitting the ball hard. If he does that – maintains a good process – he will make outs sometimes (even when he hits the ball hard, like Willie McCovey) but the hits will take care of themselves. That’s the Billy Walters process analogized to baseball. Maintaining good process is really hard to do psychologically, emotionally, and organizationally, especially when success is just “five stinkin’ feet” away. But it is absolutely imperative for investment success (as well as for gambling success and baseball success too). “We have no control over outcomes, but we can control the process,” Michael Mauboussin emphasizes. “Of course, outcomes matter, but by focusing our attention on process, we maximize our chances of good outcomes.” The bottom line should be clear – process is paramount.

______________

This post is the sixth in a series on Investment Beliefs. Such stated beliefs can suggest a framework for decision-making amidst uncertainty. More specifically, one’s beliefs can provide a basis for strategic investment management, inform priorities, and be used to ensure an alignment of interests among all relevant stakeholders.

Copyright © Robert P. Seawright, Above the Market