by William Smead, Smead Capital Management

In this five-part series leading up to the Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting, we discuss the keys to Warren Buffett’s investment success. We believe these keys are available to all of us and are a part of the discipline of stock-picking at Smead Capital Management.

How many times have you stood in line at one of your favorite establishments and said to yourself, “I wish I owned this business?” Rather than just wish you owned it, why don’t you add it to the list of companies you would buy into if it ever went on sale? This is part of the genius of Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger. Here is the list of what they look for when buying all or part of a business:

- Understandable

- Businesses with favorable long-term economics

- Run by Trustworthy Management

- Selling at Sensible Prices

Before we discuss these four seemingly simple tenets that Buffett and Munger look for in the businesses they want to own, we must discuss why Buffett and Munger want to own businesses for a long time. First, owning a business for a long time eliminates luck as a success factor in the operation of the business. Berkshire has owned Washington Post, See’s Candy and GEICO since the early to mid-1970s. They have been through positive and negative cycles in nearly 40 years and have multiplied Buffett’s investment many times over.

Second, Berkshire eliminates frictional costs associated with owning all or part of a company via common stock ownership with long duration holding periods. The most recent study of the affect of trading costs on mutual fund performance shows that investors lose an average of 1.44% of their absolute return each year to these expenses. We reason that the same is true of engaging investment bankers often with a privately-owned company. It is our opinion that the fewer mouths to feed between you and the company you own, the better.

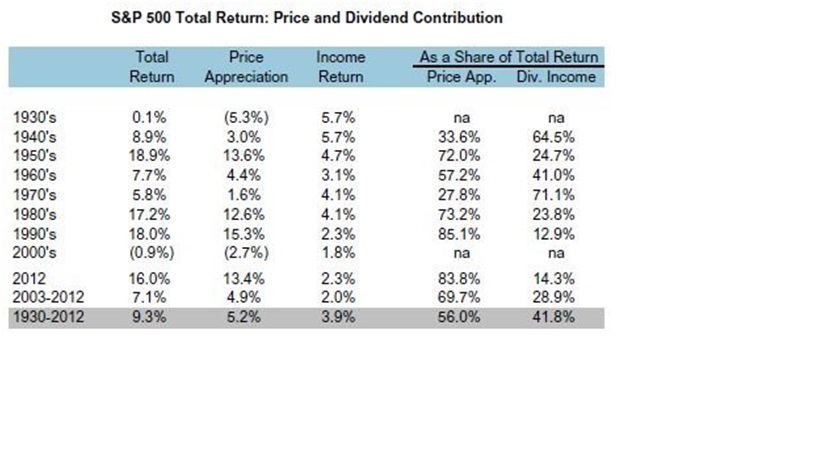

Third, Berkshire gains the maximum benefit of the free-cash flow created by the companies it owns by keeping ownership for a long time. You’ve heard Warren Buffett explain recently that he wanted IBM’s common stock price to fall the first years that he owned it because their massive free cash flow was triggering massive stock buybacks. In Buffett’s view, he will own a much larger part of the entire company if that happens. Besides shrinking the float, the company can raise dividends and make smart acquisitions with the cash. Many studies show that over long time periods (50 years) dividends make up over 40% of the total return from owning common stocks.

Back to Buffett and Munger’s checklist for acquisition. We like to say that if we can’t explain a business in forty-five seconds, we don’t want to own it. Buffett’s “circle of competency” is a big factor in what is understandable to him. When you go to Wells Fargo (WFC), Starbucks (SBUX) or Home Depot (HD) do you have any problem understanding what they do and/or why they succeed? Buffett needs to understand it today and understand why it will be a great business in twenty years. Is there any chance that someone will supplant Disney (DIS) as the world’s greatest baby sitter or producer of wholesome family entertainment?

Buffett and Munger want very favorable long-term economics attached to their partially or wholly-owned businesses. They like addicted customer bases, high and sustainable profit margins, and wide moats for defending those high margins. We like to say that if you put 100 people in a room and name a generic product, you’ve won the game ahead of time if the majority of people name your company. Examples for Berkshire: the generic product is the dip cone and the company is Dairy Queen; a soda pop is a Coca Cola (KO); a hamburger is a “Big Mac” (MCD). For us: gourmet coffee is a Starbucks; tax preparation is HR Block (HRB); and women’s shoes are Nordstrom (JWN).

Buffett and Munger want very favorable long-term economics attached to their partially or wholly-owned businesses. They like addicted customer bases, high and sustainable profit margins, and wide moats for defending those high margins. We like to say that if you put 100 people in a room and name a generic product, you’ve won the game ahead of time if the majority of people name your company. Examples for Berkshire: the generic product is the dip cone and the company is Dairy Queen; a soda pop is a Coca Cola (KO); a hamburger is a “Big Mac” (MCD). For us: gourmet coffee is a Starbucks; tax preparation is HR Block (HRB); and women’s shoes are Nordstrom (JWN).

Buffett used to say that he wanted to own a business that was so good it could be run by a “ham sandwich”. Since then he has been through enough episodes where a great business was being run by a less than stellar manager. At entry, he and Munger demand trustworthy management. Carol Loomis points out in her new book on Buffett, Tap Dancing to Work, that Warren had to help another board member replace the CEO of Coke in the early 2000s.

Lastly, Buffett likes to buy at a bargain price. He wants a great business at a reasonable price, or loves to come after a great business when tribulation has intimidated other market participants. In last week’s missive we covered the fact that valuation matters dearly to Buffett and Munger. They like to “jump over low hurdles”.

In summary, we covered a few of the benefits of long-duration ownership of wonderful companies as practiced by Berkshire Hathaway and the basic checklist that Buffett and Munger require for acquisition of part or all of a company.

Next week: Buffett’s Definition of High Quality

Best Wishes,

William Smead

The information contained in this missive represents SCM’s opinions, and should not be construed as personalized or individualized investment advice. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It should not be assumed that investing in any securities mentioned above will or will not be profitable. A list of all recommendations made by Smead Capital Management within the past twelve month period is available upon request.

This Missive and others are available at smeadcap.com

Copyright © Smead Capital Management