by Gershon Distenfeld, AllianceBernstein

It’s easy to spot a bubble after it bursts. Just follow the carnage—significant, and sometimes complete, losses for investors. It’s not so easy to pinpoint a bubble beforehand, but many are convinced that there’s too much air rushing into high-yield bonds today.

High yield may be a bit pricy these days, but we don’t see a bubble building. In fact, we think the structural characteristics of bonds and the behavior of bond investors make a bubble nearly impossible.

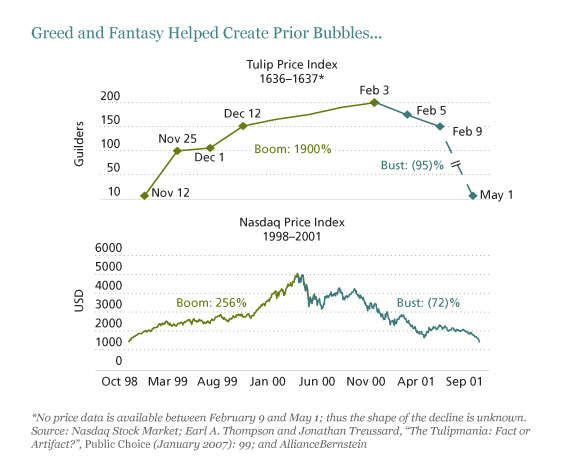

What makes a bubble? Greed is a big factor in creating financial bubbles. Dutch tulip buyers who bought at the height were wiped out when tulip mania collapsed in 1637. Owners of high-flying tech stocks lost a lot of money in 2000 (displays, below). And US housing prices show that purchasers lost tremendous value when that bubble popped. The damage is made worse because many buyers borrow money in the hopes of profiting even more in tulips or tech stock or property.

Bubbles also have an element of fantasy. In hindsight, it seems that investors have misunderstood or simply ignored the fundamental characteristics of what they’re investing in. The cash flow these assets generate can’t justify their inflated prices. The only hope is to sell the investment to someone else at an even higher price to earn a profit. (In investing, this is known as the “greater fool” theory.)

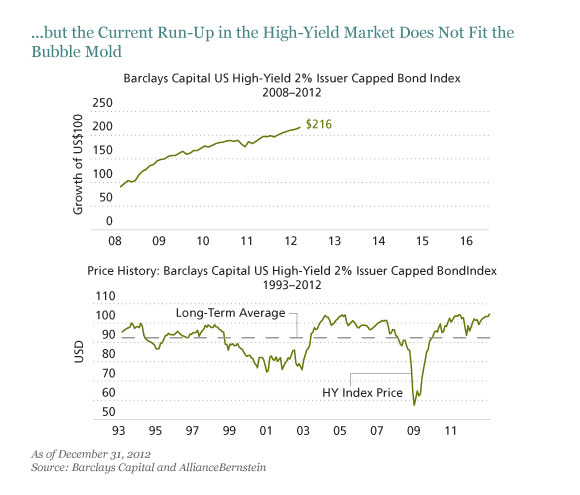

How much air is really in high yield?According to our analysis, not much. Sure, high-yield returns have been extraordinary the last few years and yields are at all-time lows. But high-yield bonds, like most other bonds, have a known ending value. As long as the issuer doesn’t go bankrupt, investors get back the entire face value when the bond matures.

With average high-yield bond prices reaching all-time highs near $105, investors should watch the valuations. But investors know they’ll get $100 back at maturity (barring default), so forecasting high-yield bond returns is a lot easier than forecasting stock returns. Getting full value at maturity—or maybe a bit more if the issuer “calls” the bond at a slightly higher price, which happens quite often—makes it less likely that investors will suffer the extreme losses seen in bursting bubbles. Plus, investors who hold overvalued bonds know that they might lose money, so there’s a built-in incentive to keep prices in a reasonable range. Strong returns don’t portend a bubble when prices are still within spitting distance of their long-term average (displays, below).

Now of course, if the companies issuing these bonds were all being managed with aggressive leverage and defaults were likely, we’d worry more. But that’s not the case: credit fundamentals in high-yield companies today are actually quite strong, with reasonable leverage ratios and balance sheets. So forecasts for future defaults are actually well below historical averages.

Why are high-yield bond prices so high? It’s because they pay attractive income to investors, and income is in high demand. It’s not surprising that income-producing assets are trading at a premium. But based on where the market stands, we think investors would be naïve to expect anything higher than single-digit returns in 2013.

That’s hardly the type of return that inspires greed-induced bubbles.

Could investors lose money? Of course—that’s always the case. As a matter of fact, in nearly two-thirds of the calendar years since 1990, the high-yield market has experienced peak-to-trough drops of at least 5%. In more than one-third of all years, the market has seen drops of more than 10%. High-yield investors should be ready for it—that type of volatility is normal.

But we don’t think there’s risk of the high-yield market being in a bubble, even if these bonds are a bit expensive. And the fact that people are asking questions about bubbles is healthy, in our view.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AllianceBernstein portfolio-management teams. Past performance of the asset classes discussed in this article does not guarantee future results.

Gershon Distenfeld is Director of High-Yield Debt at AllianceBernstein.