September 21, 2012

by Rob Williams, Director of Income Planning, Schwab Center for Financial Research

and Kathy A. Jones, Vice President, Fixed Income Strategist, Schwab Center for Financial Research

The Schwab Center for Financial Research presents Bond Insights, a bi-weekly analysis of the top stories in today's bond markets. This issue includes our observations on the Federal Reserve's announcement of its latest version of quantitative easing (QE3), we discuss bank bonds and if we believe they could present an opportunity for fixed income investors in the current environment, we take a look at the many differences and similarities in the way municipal governments are managing credit challenges and we discuss the impact of low interest rates on bond investments.

"To Infinity and Beyond"

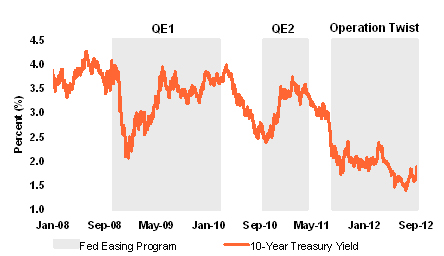

The Federal Reserve's announcement of its latest version of quantitative easing (QE3) managed to exceed the market's expectations even though it was widely anticipated. The Fed announced an open-ended bond purchase program of $40 billion per month concentrated entirely in mortgage-backed securities and extended the time period it plans to keep interest rates on hold until mid-2015. Fed Chairman Bernanke made it clear that the committee's goal is to reduce the unemployment rate, which he called, "a grave concern." Long-term Treasury bond yields surged to a four-month high on the news. Is this the start of the long-awaited bear market in bonds?

- It is too soon to tell. Rising bond yields are consistent with the market's response to previous rounds of QE. In the initial phases of QE1 and QE2, bond yields rose as well because investors shifted into riskier assets and out of Treasuries. As the Fed's bond buying ended however, interest rates drifted lower again as the pace of economic growth and inflation ebbed. With QE3 the Fed is leaving the time frame for bond buying open ended.

- One view on the impact of a third round of asset purchases is… that the Fed's actions will ignite inflation pressures through the weaker dollar and rising asset prices, sending bond yields higher. Another view is that the bond buying will prove ineffective because the economy's problem is not a lack of liquidity but a lack of demand. Therefore, interest rates will decline again once it is clear that the economy is not responding to monetary policy.

Market Reaction to Fed Easing

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve and Bloomberg, monthly data as of September 18, 2012.

- We believe both views have some validity. The previous rounds of quantitative easing were larger on a per-month basis at over $70 billion per month, but the commitment to an indefinite time period may signal that the Fed is willing to tolerate more inflation in exchange for stronger growth. If QE3 results in a weaker dollar, then rising import prices can put upward pressure on the consumer price index (CPI). But rising prices of imported goods, such as oil, may lead consumers to lower consumption in other areas. With weak income growth, demand could remain lackluster and inflation pressures contained.

- It may come down to a matter of timing. Inflation expectations are already rising, but higher inflation may not surface until later when the economy has less excess capacity. That means watching for improvement in labor markets and a pick up in demand while watching inflation expectations.

- In our view, the major risk in current monetary policy is… that the Fed overstays its welcome by pumping too much liquidity into the economy for too long, allowing inflation to become embedded. That is a risk they appear willing to take in exchange for the potential to prevent a renewed recession and/or deflation.

- Bottom line: Whichever view you adhere to, long-term Treasury bond yields at or below the rate of inflation offer very little value beyond diversification, in our view. There is clearly more room for rates to rise than to fall. However, we don't advise trying to time the interest rate cycle. We continue to favor laddered portfolios where the average duration is in the short-to-intermediate term region. We also believe investors should consider holding high quality bonds for the bulk of their portfolios, limiting the higher-yielding, more aggressive sectors of the market to no more than 20% of the fixed income allocation.

Bank Bonds—Post Downgrades

It's been almost three months since Moody's downgraded fifteen global banks on June 21. Although the downgrades had been well-publicized in advance, the degree of downgrades was uncertain. As it turned out, the downgrades were not as severe as markets may have expected. Meanwhile, the stock market has risen, domestic bond yields are higher, and central banks across the globe have taken measures to boost their slowing economies. Given this, how has the financial sector of the bond market fared since the downgrade, and do financial bonds present an opportunity now for fixed income investors in the current environment?

- Financial institution bonds have outperformed other sectors of the bond market. From the date of the downgrades through September 18, the Barclays U.S. Corporate Bond—Financial Institutions Index generated a total return (price change plus interest income) of 4.33%. For the same time period, the industrial and utility sub-sectors of the Barclays U.S. Corporate Bond Index saw total returns of just 1.93% and 1.05%, respectively.

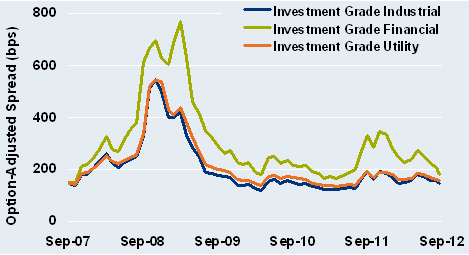

Barclays U.S. Corporate Bond Yields by Sector

Note: Option-adjusted spread (OAS) is the basis point spread relative to Treasuries, net of the cost of any embedded options

Source: Barclays, monthly data as of September 17, 2012.

- Tighter yield spreads are one of the main drivers behind the strong performance. When bonds are perceived to have greater risks they will trade at higher yields relative to bonds with lower credit risk, such as Treasuries, in order to compensate. Yield spreads on financial institution bonds have narrowed since the downgrades. This may seem counterintuitive, but the market may have been expecting deeper downgrades. Only one of the institutions was downgraded by three notches. The rest were smaller. The yield spread of the financial index above the Treasury index dropped from 2.6% the day before the downgrade to 1.8% on September 18. This is the lowest spread since July 2011.

- What has happened to banks since the downgrades? Not much, in our view. From a purely bank-specific point of view, it's been quiet. Second quarter earnings appeared neither to excite nor disappoint the markets, and aside from the large trading loss at a major bank earlier in the year, domestic banks have done their best to stay out of the headlines. But many macro factors have supported the financial sector. The S&P 500® Index is up over 8% since the downgrades, the Federal Reserve announced another round of quantitative easing, U.S. government bond yields are higher, and the European Central Bank took steps to address its debt crisis. Banks are often considered leveraged plays on an economy and when the central banks provide more liquidity to the economy, riskier segments of the market generally tend to do well. When riskier segments of a market begin to perform well, financials often tend to follow suit.

- But there are still a few unknowns in the financial sector. Although risk premia may have fallen, financial companies still face a number of headwinds, in our view. Financial regulation has yet to be finalized. Without some rules set in stone, many firms will hold off making investment decisions. And the economy can still be described as "sluggish," which may continue to weigh on corporate earnings. Many banks have been cautious lately about their future earnings, citing earnings growth as one of their main concerns. Although financial firms' balance sheets may be strengthening, lower earnings growth may affect investor confidence, in our opinion.

- Bottom line: Financial bonds may make sense for investment grade corporate bond investors, but we would caution not to overweight the sector. This can be difficult, as financial institutions make up over 32% of the corporate bond index.

Although financials have generated a positive total return over the past few months, it may be difficult to continue the strong pace. Financial bonds currently offer a higher yield, on average, than their industrial and utility counterparts, but we believe investors should take a diversified approach when buying individual corporate bonds.

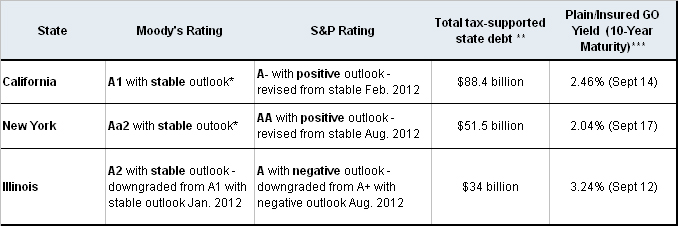

California, New York and Illinois Rating and Outlook Changes

We've seen several notable rating and outlook changes recently for a handful of large states, including California, New York and Illinois. These rating changes remind us that there are as many differences as similarities in the way municipal governments are managing credit challenges. Even at the state level, it's not a homogenous market. A key factor to watch is "structural budgetary balance"—whether you're looking at states or local municipalities. Structurally balanced means that the revenues and expenditures essentially match without the need for one-time cuts that go away later and don't address long-term challenges.

- California's A- rating outlook positive from Standard & Poor's. California is S&P's lowest-rated U.S. state, at A-. But the agency revised their outlook on the rating to positive from stable in February of this year and affirmed their rating and outlook on September 13. The state's outlook was revised to positive in part because the legislature successfully passed a timely state budget in June 2012, according to S&P—a feat they've had trouble achieving recurrently in prior years. Credit quality also hinges on the sustainability of recent cuts, they say. Will those budget cuts carry over into future years to limit the need for additional cuts if revenues don't rise? A tax-raising measure (Prop 30) on the fall ballot would also boost revenue and limit the need for $2.5 billion in education cuts. The state legislature also passed reforms in late August to reduce pension contributions for new employees, a factor cited as a positive factor by both S&P and Moody's. The state plans to sell $1.6 billion in General Obligation (GO) bonds on September 25.

- New York's AA outlook from S&P is also positive, revised from stable at the end of August. Like California, S&P based their change in outlook on "movement toward structurally balanced budgets in the past two years." This "structural" alignment of revenues and expenditures is one of the key factors agencies look at when assessing credit quality. The size of the state's budget deficits have also been shrinking with lower projected "out-year gaps"—a positive for any state, especially if state revenues continue to gradually improve, led (for most states) by income and sales tax.

- Illinois rating downgraded to A from A+ with negative outlook… also by S&P in August. Pension reform, and lack of any "meaningful action" on that front, was the primary reason for S&P's rating downgrade in late August, according to the agency report. Analysts have often pointed to Illinois—along with California, one of the lowest rated by both S&P and Moody's—for their relative lack of progress in addressing a sizable unfunded future pension liability (amounting to $82.9 billion at the end of fiscal 2011, with a 43.4% "funded ratio"—meaning the ratio of assets/investments set aside to match the total estimated future pension costs) and lack of progress in containing costs or raising revenues to improve "structural budget performance." Moody's affirmed their A2 rating with stable outlook in August, but also cited the failure to enact pension reform as a "credit negative." We see the same theme: the need to balance revenues and expenditures on an ongoing basis, balancing funding for current and long-term obligations.

*No change in rating or outlook in 2012

**Source: Standard & Poor's

***Source: Bond Buyer

- Do ratings matter? If you're skeptical of bond ratings as an indication of credit quality, you're not alone. Ratings are opinions, not a guarantee of credit quality. But we still see them as a useful tool in monitoring which issuers are making changes to manage long-term budgetary balance. Rating changes may not lead to an immediate change in performance. But right now, investors are already being compensated in the form of higher yields (as shown in the table above.) Over the long-term, however, investors focused on ability to pay—we believe—should focus on issuers with a pattern of managing credit quality. You can find rating reports when searching for individual bonds on schwab.com. Or speak with your Schwab Financial Consultant or a Schwab fixed income specialist.

- Bottom line: For U.S. states, we see ratings as a reminder of the differences in credit quality in the muni market. This includes U.S. states, where credit quality hinges on structural balance between revenues and service obligations.

Interest Rates Are Low—Should You Sell Your Bonds?

If you've been holding bonds and bond funds for more than a few years, it's likely that you have gains in your portfolio. Just in the last two years, ten-year Treasury yields have fallen from nearly 4% in early 2010 to under 2%. And as yields fall, prices rise. With interest rates at low levels, we concede that there isn't much room for rates to fall further. And if they start to rise, bond prices will fall, erasing paper gains from bonds with higher coupons pricing at premiums now. But selling bonds that have appreciated means losing the income that they generate and replacing that income will be difficult in most cases— without taking more risk. How do you know when its time to sell?

- What's your goal? If you are looking for total return in your portfolio, then it might be time to take some profits in portions of the fixed income portfolio that appreciated most in price, since it doesn't appear that bond prices have a lot of upside from here. Certain sectors, in particular long-term bonds, will also experience losses if rates rise. For investors in bond funds, the downside in price can be a particular concern since the net asset value (NAV) of the fund will decline if interest rates rise, all else being equal. Unlike individual bonds, you may not get back the full amount of the principal you've invested, depending on when you need the money or need to sell.

- If you sell bonds or bond funds that have appreciated in value, however, you will lose the income that they generate. And replacing that income may mean taking more risk. For income-oriented investors, this is a challenge. For example, if you purchased an investment grade corporate bond with a 5% coupon several years ago, it might be trading 10% or more above its par value. If you sell now and realize that 10% capital gain, then you've added to the cash balance in your portfolio. But you've taken away the regular 5% coupon as well. The average yield on investment grade bonds is now under 3%, as measured by the Barclays US Corporate Bond Index, so the additional principal you have available to invest may not make up for the reduced income you will receive.

- To get the equivalent yield, you would probably have to invest in lower quality bonds. This may include high yield bonds and other sectors that may not be appropriate for your risk profile. Extending maturities is another way to increase yield, but that adds risk. Long-term bonds with less credit risk, starting with Treasuries, are also the sectors that have appreciated in value the most. Moreover, you will have a capital gain from the sale of your bond, which is taxable. If you are an income-oriented investor, the trade off may not make sense.

- For total return investors, it's always a good idea to revisit your asset allocation and determine if it's in line with your long-term goals. If the fixed income portion of your portfolio has risen in value and out of balance with the targeted allocation, it may be a good time to re-balance by selling some bonds or bond funds and re-allocating to other sectors where you may be underinvested. But other investors may hold fixed income investments primarily for the income that they generate, or they are under-allocated to bonds based on their time horizon and tolerance for equity risk. In this case, selling bonds to realize gains will reduce income and may actually increase the risk in the portfolio by pushing into lower credit quality investments or investments with equity risk. When looking at the strategic asset allocation, buy-and-hold investors might also choose to measure the allocation to bonds in terms of the par value rather than the market value.

- Bottom line: If you buy and hold bonds, the gain on your bond portfolio is a temporary reflection of the shift in interest rates—the market's reflection of the benefit in holding bonds with higher coupons than available at par in the market today. The gain on its own is not necessarily a reason to reallocate away from fixed income or sell individual bonds, in our view. Those gains will gradually decline as the bonds approach maturity. In the meantime, you would realize those gains over time in the form of a higher coupon. The choice to sell, or hold, should depend on your objective—do you prefer income that you might not be able to easily replace, or do you prefer to take gains and then reallocate to other investments that are more in line with a long-term strategic allocation? For help, talk with your Schwab Financial Consultant or a Schwab fixed income specialist.

For other articles, please visit schwab.com/onbonds.

Important Disclosures

Fixed income securities are subject to increased loss of principal during periods of rising interest rates. Fixed income investments are subject to various other risks including changes in credit quality, market valuations, liquidity, prepayments, early redemption, corporate events, tax ramifications and other factors.

Lower-rated securities are subject to greater credit risk, default risk and liquidity risk.

Income from tax-free bonds may be subject to the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), and capital appreciation from discounted bonds may be subject to state or local taxes. Capital gains are not exempt from federal income tax.

This report is for informational purposes only and is not an offer, solicitation or recommendation that any particular investor should purchase or sell any particular security or pursue a particular investment strategy. The types of securities mentioned herein may not be suitable for everyone. Each investor needs to review a security transaction for his or her own particular situation.

All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice in reaction to shifting market conditions. We believe the information obtained from third-party sources to be reliable, but neither Schwab nor its affiliates guarantee its accuracy, timeliness, or completeness.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Diversification strategies do not assure a profit and do not protect against losses in declining markets.

Examples provided are for illustrative purposes only and not intended to show actual investments or to be reflective of results you should expect to attain.

Barclays U.S. Corporate Bond Index covers the USD-denominated investment grade, fixed-rate, taxable corporate bond market. Securities are included if rated investment-grade (Baa3/BBB-/BBB-) or higher using the middle rating of Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch. This index is part of the U.S. Aggregate.

S&P 500® Index is a market-capitalization weighted index that consists of 500 widely traded stocks chosen for market size, liquidity, and industry group representation.

Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses and cannot be invested in directly.

The Schwab Center for Financial Research is a division of Charles Schwab & Co., Inc.