August 20, 2012

by Liz Ann Sonders, Senior Vice President, Chief Investment Strategist, Charles Schwab & Co., Inc.

Key Points

- PIMCO founder Bill Gross believes the "cult of equity is dying" … let me take the other side.

- Mutual-fund flows suggest that we may have lost a generation of investors.

- However, demographics suggest there may be another generation that could be the stock market's savior.

Rumors of the death of equities may be greatly exaggerated. Bill Gross, founder of PIMCO, recently wrote that the "cult of equity is dying," and of course it generated a furor of interest. In a separate Tweet, Mr. Gross noted that disillusion with stocks "might be a generational thing." I have great respect for Bill and was very fortunate to share the stage with him at the opening of last year's Schwab IMPACT conference. He was no more optimistic then than he is now and several media outlets that covered the conference called me the "optimistic ying to his pessimistic yang."

Bill's recent comments didn't do much more than repeat the view he's held for some time. I remember reading back in February 2009 an interview he did with Forbes Magazine in which he opined, "…things will never be the same. Risk taking has been destroyed and any animal spirits must come from Washington. Global growth rates—low, low, low—asset classes will be readjusted for that outlook. That is—stocks will be more of a subordinated income vehicle as opposed to a 'stocks for the long run' growth vehicle."

Not just a lost decade … a lost "baker's dozen"

Needless to say, the timing of those comments was not ideal as the stock market bottomed the following month and has since doubled. This missive is by no means an attempt to discredit Bill or his views, as there's a lot of truth to what troubles him. Frankly, they're the same truths that continue to plague the psyche of the majority of individual investors that are indeed shunning stocks as if the recent lost decade (or, more precisely, lost "baker's dozen" given that the S&P 500 index is presently at levels equivalent to where it traded back in 1999) will be repeated.

I know that this opinion may elicit many of the same comments I've heard following other contrarian views I’ve expressed over the past three years—that I'm yet another "perma-bull" with blinders masking long-term structural problems that will forever plague stocks. First, I'm not a market timer, but I'm also not a perma-bull. Long-time clients may recall we were decidedly pessimistic about the outlook for both the economy and stock market leading into the 2007 top and didn't turn optimistic until the spring of 2009.

I remain optimistic longer-term, albeit it with near-term concerns due to the obvious pressures still with us thanks to the ongoing eurozone crisis, the looming US fiscal cliff and related election uncertainty, and slowing global growth. But it's the longer term that's the focus of today's report.

Being a contrarian

I'm never a contrarian just to be contrarian, but sometimes tacking against the winds of the market and investor psychology can be amply rewarded. Stock market sentiment has always been driven by what the market has done in the past, not by a fundamentally based consideration of what might lie ahead.

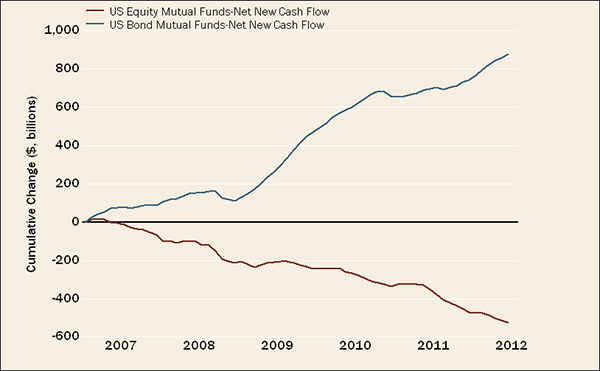

Short-term sentiment measures will always ebb and flow with market action, but most longer-term sentiment measures show a level of despair about stocks unmatched in the post-World War II era. One need look no further than mutual-fund flows: the chart below shows a $1.4 trillion spread between bond-fund inflows and stock-fund outflows—a spread unmatched in history.

An Unprecedented Show of Risk Aversion

Source: FactSet, Investment Company Institute, as of June 30, 2012.

A wave of shocks

The inflows to bond funds are easy to explain given strong returns (until recently). But they're also characteristic of aging Baby Boomers' risk aversion and reactions to a veritable wave of shocks to both the system and investors' psyche, including, but not limited to:

- The lost decade (or as previously mentioned, the lost "baker's dozen")

- The dramatic decline in the stock market from 2007 to 2009

- Periods of unprecedented market volatility

- The 2010 "flash crash"

- The growing dominance of high-frequency trading and its effect on market behavior

- The 270-point average daily Dow swing in 2011's August-November span related to Standard & Poor's downgrade of US debt and the debt-ceiling debacle

- Facebook's disastrous initial public offering and subsequent price performance

- JP Morgan's huge trading loss earlier this year

- Another Ponzi scheme in the form of Peregrine Financial Group (and related attempted suicide by its founder), coming on the heels of the Bernie Madoff and Allen Stanford scandals

- The "LIBORgate" rate-setting scandal

The bottom line is that the demise of interest in stock investing by many individual investors is in very large part due to a total lack of trust in the transparency and fairness of the market. This is understandable.

I often get asked whether there's any hope for the market longer-term if individual investors remain on the sidelines. History may be a guide. As noted by The Leuthold Group this spring, there were two stock market climbs the public missed. The first was the advance from 1974 to 1980, which lasted more than six years and amounted to a 120% gain for the S&P 500, and a multiple of that gain in small-cap stocks. However, US-focused mutual funds enjoyed net inflows in only 15 months during this run. The shallow bear market of 1976-1977 likely shook out many would-be buyers … and contrarians might note the high of that entire move coincided with the first sizable month of net inflows.

More recently, during the current cyclical bull market (since March 2009) there have been two sharp declines in both mid-2010 and mid-2011. They probably served the same purpose as the 1976-1977 decline—scaring off many retail investors just as they were finally preparing to tiptoe back in. It's hard to fathom that a majority of individual investors could remain sidelined in the face of a continued strong rally in stocks, but the late 1970s showed that it can happen.

Back to demographics and the "Millennials"

In history, few forces have been as strong behind stock returns as demographic trends: movements in population, age, gender and employment status, among others. Much focus has been on Baby Boomers, especially as they begin to retire, and their effect on markets in the future. Yes, they're now more risk-averse than ever, and this is not likely to change. But what about a key generation behind them?

Those born after 1980 are generally considered "Millennials," but I prefer the description "Echo Boomers," as they represent many of the children of Baby Boomers. Millennials are often characterized as having less financial savvy and weaker job prospects than their Boomer parents. The result is an impression of a generation equally as disenfranchised from the stock market as the Baby Boomers.

However, I think many may be underestimating the positive impact this generation may have on investing trends. I recently read an interesting report on the subject by Turner Investments in which it noted that the Millennials are "digital natives"—the first generation raised with technologies such as personal computers, the Internet and smartphones that prior generations had to adapt to later in life.

My two children (ages 12 and 16) can't fathom that I had to rely on libraries, books, encyclopedias and a typewriter when I was a college student. But they're part of a generation that's become completely reliant on "new" technologies. Eight of 10 of Millennials sleep with their cell phones in reach (count my kids in the 20% that don’t, though they would if we let them).

The Millennials are highly educated: About 40% of college-age Millennials are enrolled in higher education—the greatest percentage in US history. Yes, some of that's a result of the rough economic ride they've been on over the past decade or so. They've had to suffer two economic/market crises since 2000, starting with the bursting of the technology bubble and followed by the bursting of the housing bubble and the attendant financial crisis. The dearth of jobs has hit the generation particularly hard. About a third of 18-29 year olds are unemployed, under-employed or simply out of the work force.

Don't underestimate the Millennials

Turner offers seven reasons why the financial prospects of Millennials may be much better than is popularly supposed and why Millennials may "bring about a Great Bull Market of the 21st Century":

- The Millennial generation is huge at more than 85 million—even larger than the Baby Boomers' 81 million. It wasn't until Boomers were in their 30s that they began to truly make their presence felt in the stock market. The great bull market of the last century was the result. My additional perspective: vehicles like 401(k)s make it easier and more "automatic" for this cohort to invest.

- Millennials' financial struggles thus far are actually fairly typical of early adult life: paying for education, finding a first job, relocating, buying a first house and learning the vocational ropes.

- Macroeconomic headwinds facing Millennials—notably high unemployment and depressed housing—are likely to be temporary. My additional perspective: housing has likely already found its bottom and household formation has jumped significantly since its lows.

- Baby Boomers once faced similar macroeconomic headwinds (during the late 1970s and early 1980s), but were still able to subsequently invest in stocks and drive the market to new highs during their peak earning years.

- Despite all of their financial troubles, Millennials are savers and are already investing in stocks. Twenty-something investors have more stocks in their 401(k) accounts today than their counterparts did a decade ago, according to the Investment Company Institute. About 80% of 20-somethings had devoted at least 60% of their 401(k)s to stocks in 2010 (the latest year of data) versus 70% in 2000.

- Millennials tend to be optimists and are more willing to take risks relative to their parents' generation. About 29% of all entrepreneurs are Millennials, according to the Kaufman Foundation, suggesting an appetite for risk.

- Millennials are putting emerging nations in a demographic sweet spot. The ratio of workers to the total populace in East Asia rose from 47% in 1975 to 64% in 2010. In Latin America the ratio rose from 44% to 56%, and in South Asia it rose from 45% to 55%. A sizable new class of investors is surfacing around the globe.

Food for thought.

Important Disclosures

The information provided here is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered an individualized recommendation or personalized investment advice. The investment strategies mentioned here may not be suitable for everyone. Each investor needs to review an investment strategy for his or her own particular situation before making any investment decision.

All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice in reaction to shifting market conditions. Data contained herein from third party providers is obtained from what are considered reliable sources. However, its accuracy, completeness or reliability cannot be guaranteed.

Examples provided are for illustrative purposes only and not intended to be reflective of results you can expect to achieve.

Copyright © Charles Schwab and Company