Submitted by John Aziz of Azizonomics

The Deleveraging Trap

Hayekians and Minskians agree on one key thing: an increase in debt beyond the underlying productive economy is unsustainable.

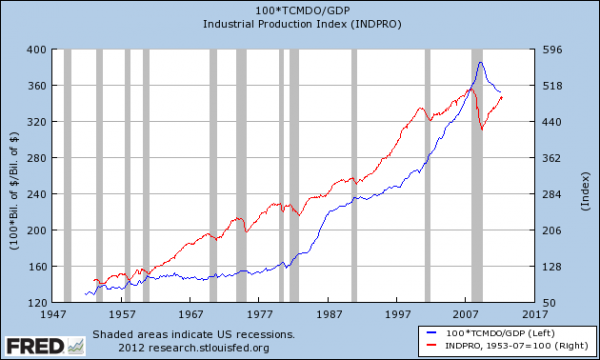

In my view, the key figures in defining this are total debt as a percentage of GDP, and its relationship with industrial production. Debt as a percentage of GDP tracks how much debt there is relative to one measure of economic activity, GDP. Yet GDP is a very limited tool of measurement; all GDP really tracks is the circulation of money. To get a clearer sense of the true relationship with underlying productivity, it is useful to compare the ratio of debt-to-GDP with the level of industrial production.

Up ’til the ’70s, debt-to-GDP grew more slowly than industrial production. That is healthy and sustainable. While the total market debt may grow in tandem with GDP, and with industrial production — indeed, this can be the case even under a gold exchange standard (as the gold supply increases) — there is no sensible reason for the ratio of debt-to-GDP to grow faster than industrial production. Indeed, this is symptomatic of just one thing — consumption without income, enjoyment without effort, living beyond the means of productivity. This is just an unsustainable bubble.

As the ’90s turned to the ’00s and the United States gains in industrial production ceased to accumulate, while GDP and most concerningly (and hilariously) while the debt-to-GDP ratio continued to increase. This was classical bubble behaviour, and the end came very poetically; the recession and the industrial production collapse hit just as growth in the debt to GDP ratio (as indexed against 1953 levels) finally surpassed growth in industrial production. Indeed, I hypothesise that a very strong indicator of a Minsky moment — when excessive indebtedness forces systemic deleveraging, leading to price falls, leading to widespread economic contraction — is the point when long-term growth in the debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds long-term growth in industrial output.

The debt-to-GDP ratio is gradually falling, yet it is still at a far higher level than the historical average, and it is still proportionately higher than industrial output. And at the same time, consumers are re-leveraging, and government debt is soaring. And industrial production is barely above where it it was a decade ago, and far below its pre-2000 trend line. We have barely started, and already this has been a slow and grinding deleveraging; rather than the quick and brutal liquidation like that seen in 1907 where the banking system was effectively forced into bailing itself out, the stimulationist policies of low rates, quantitative easing and fiscal stimulus have kept in business zombie companies and institutions carrying absurd debt loads. Like Japan who experienced a similar debt-driven bubble in the late ’80s and early ’90s, we in the West appear to have embarked on a low-growth, high-unemployment period of deleveraging; and like Japan, we appear to be simply transferring the bulk of the debt load from the private sector to the public, without making any real impact in the total debt level, or any serious reduction in the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Cutting spending — for both the private sector and public sector — is problematic. My spending is your income; as spending falls, income falls, which leads to more consumers, producers and governments attempting to deleverage. This leads to more monetary easing, simply to keep the zombie system stable, and keep the zombie debt serviceable. More consumers and producers can take on debt, at least for a time, but the high residual debt level makes any great expansion of productivity or growth challenging, as consumers and producers remain focussed on paying down the pre-existing debt load. It is a vicious cycle.

Quantitative easing does not even tackle the main challenge: reducing the debt load. In fact, it is targeted at precisely the opposite — increasing the debt load, by encouraging lending. But lending into a society that is already heavily indebted leads to no great uptick in productivity, because consumers and producers are already over-indebted to begin with, so few can afford new debt. And banks — flush with cash — have no real incentive to lend; the less they lend, the more deflationary conditions are prone to become, increasing the purchasing power of their excess reserves (on which the central bank already pays interest). The outcome is greater economic stagnation, ’til the next round of monetary easing which leads to a brief uptick, and then further stagnation.

To break out of the deleveraging trap, the debt load needs to be drastically reduced. In my mind there are three potential pathways there, each with various drawbacks and advantages:

- Liquidation; when a debt-driven crash happens, the central bank stands back and lets it happen, as happened in 1907. Prices will drastically fall, many companies and banks and debt will be liquidated, until the point at which prices have fallen to a sustainable level. But we may have missed the boat — the crash already happened, the system has already been bailed out, and the financial system today has already become zombified. And under a system where the central bank determines the availability of money and the level of interest rates this approach has in the past led to excessive central-bank-enforced liquidation, from which the economy may struggle to recover, as happened after 1929.

- (Hyper)inflation; the central bank prints money and injects it into the economy via the banking system. Prices rise, wages rise, and the nominal debt remains the same, thus reducing the debt burden. While most economists who advocate such an approach advocate a slightly elevated level of inflation, the higher the rate of inflation, the more the residual debt load will be devalued; under a Weimar-style regime, mortgages could be repaid in a week. Unfortunately inflation is nonuniform; whoever gets the money first (i.e. banks) can buy up assets on the cheap, and pass the cost of the inflation down the chain of transactions. As Keynes himself noted: “By a continuing process of inflation, governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens.” Inflation discourages savings and capital formation, which are necessary for new growth. And most significantly — as the Fed’s experiment with QE shows — inflation unless it is very severe will not even necessarily have much bearing on reducing the debt-to-GDP load. The results of a severe (hyper)inflation could be very chaotic and dangerous.

- Debt Jubilee; the central bank prints money, and injects it into the economy via the citizens, with the explicit condition that they use it to clear their debts. This will have the desirable effect of directly reducing debt levels, and lifting over-indebted consumers and producers out of the deleveraging trap. Additionally, the inflation would be uniform and so not to the advantage of the banks or the financial elite. However introducing a large quantity of money to the system — even directly as a medium for debt-cancellation — does itself carry a high inflationary potential.

Certainly, the current status quo of high unemployment, low growth, sustained over-indebtedness and zombie banks and corporations surviving on government handouts is not sustainable in the long run. We shall see which route out of the deleveraging trap we take. Liquidationism seems unlikely, as central banks are afraid of the concept. Inflation (or its unintentional corollary, currency collapse) seems risky and dangerous. A debt jubilee would at least address the real problem of excessive debt, although it is in modern times uncharted territory, and would surely face much political opposition.

Copyright © Azizonomics