Quite what German intentions are remain lost in the murky underworld of European politics. They have repeatedly discarded the idea of increasing the financial muscle of the European Stability Mechanism. They continue to oppose the monetisation of Europe’s large budget deficits. They have flatly rejected any talk of a banking union. Apparently, the only policy they can’t get enough of is austerity but, as we can all testify to at this stage of the crisis, an overdose of austerity will do to European economic growth what fertiliser does to my lawn if not accompanied by ample supplies of water.

Maybe the Germans are seeking a break-up solution through blatant inactivity as some commentators have suggested – most notably Martin Wolf in the FT (see here) – but, then again, is it really in the best interests of Germany to see a break-up of the euro? I would have thought not. Germany’s largest export market is not China as some seem to think; it is the eurozone itself. A re-introduction of the deutschmark would make German exports to countries such as Italy and Spain at least 30% more expensive if not more so.

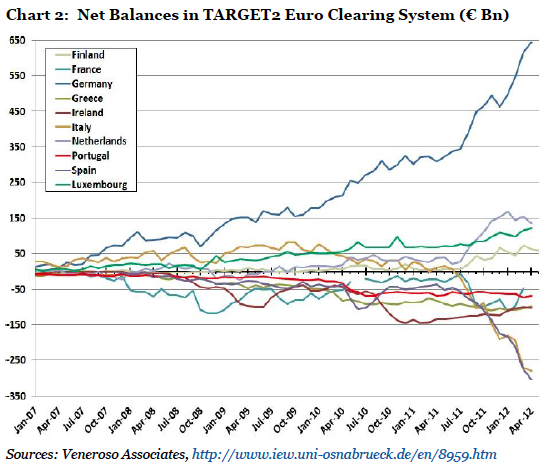

A break-up would also expose Germany to massive losses due to the large accumulated imbalances in TARGET2 - the settlement system that clears payments between central banks within the eurozone. As you can see from chart 2 below, the German central bank is easily the largest creditor in TARGET2. As at 30 April 2011, German TARGET2 claims amounted to €309 billion. One year later, those claims have ballooned to €644 billion.

This is the result of a dysfunctional banking system. European banks no longer trust each other so instead of, say, Deutsche Bank having a claim on Banco Santander in order to facilitate trade between the various eurozone members, the central banks have had to step in and provide the necessary credits. As long as the euro remains intact, these imbalances are largely academic; however, if the euro were to break up, the German central bank would find it next to impossible to recover the monies owed through TARGET2.

For those reasons I very much doubt that Germany would aim to provoke a break-up of the eurozone. It has simply got too much to lose. It is more likely that Merkel’s tough words are designed to please the domestic electorate in preparation for next year’s parliamentary elections. However, that is a high risk strategy. Southern Europe is rapidly losing its appetite for Germany’s austerity demands. Admittedly, not many Germans will be going to Greece this summer but the few who have already been are telling stories about the atrocious treatment they have received – tomatoes thrown after them in restaurants, etc. The revolt against Germany is growing and it is growing rapidly.

The first mover advantage

From a game theory perspective, the moment one of the 17 eurozone member countries realises it would be better off outside the eurozone, it has everything to gain from being the first mover. We have all been led to believe that a break-up will be devastating for everyone. That is not entirely the case. It could certainly prove disastrous for those left inside a dysfunctional currency union but for the first mover the advantages are numerous and it is only a question of time before someone in Greece, Spain, Portugal or Italy reaches that conclusion.

An exit from the eurozone would create another set of challenges but it wouldn’t necessarily spell the financial Armageddon widely predicted. The media – in particular the British – clearly enjoy the prospects of a bit of drama and do not even attempt to restrain themselves. Neither do politicians when spelling out the consequences of a break-up. Only the other day did Joschka Fisher, Foreign Minister and Vice Chancellor of Germany in Gerhard Schröder’s government between 1998 and 2005, utter the following warning:

“Let’s not delude ourselves. If the euro falls apart, so will the European Union, triggering a global economic crisis on a scale that most people alive today have never experienced.”1

The armies of financial analysts and economists employed by banks worldwide (who really should know better) do not exactly paint a rosy picture either. Cascade after cascade of dire predictions about the “end of Europe as we know it” do little for overall confidence. The problem with all these doomsday prophecies is that the history books of currency union break-ups offer little support for all that negativity. In fact, most currency union break-ups have confounded the so-called experts and led not to a collapse of society but to renewed prosperity. The hard facts suggest that this is a hurdle that can indeed be overcome and that those countries that break with the euro would most likely benefit in the long term.