Institutionalizing Courage

June 2012

by Rob Arnott, Research Affiliates (RAFI)

Imagine a boss who is generally supportive of your efforts, but has some odd tendencies around rewarding initiative. Let’s call him Mr. Market.1 Every time you go in for your annual review, Mr. Market gives you a raise which is usually 1% or 2% above inflation, and asks, “Whaddya think?” If you’re “passive” and take whatever Mr. Market offers, you wind up with a steady but modest increase in your income, year after year, assuming the company is still doing well. Mr. Market, however, does not view all projects equally. If you offer to take over some project that he hates, he boosts your raise by an average of 3–6%. With a little initiative, you can triple the average real raise—over and above inflation—that everyone else is getting.

Unfortunately, Mr. Market is also bipolar, with wide mood swings. If you’re willing to take on a project that he really hates, he may give you a 15% raise, just to get it off his desk. On the other hand, if you’re taking a project that he doesn’t much mind doing, he may actually take away some of the normal raise. Because you run this risk every time you propose to take on a new project, it takes a modicum of courage to make these offers to the boss.

With a boss like Mr. Market, what is the right strategy for success? The answer is obvious: You need the courage to stick with the profitable strategy through the good times and the tough times. We’ll come back to Mr. Market shortly. First, we need to understand the true nature of wealth, income, and spending. Sustainable Spending as a Strategy Although people tend to measure wealth in terms of the dollar value of a portfolio, we believe it is better to measure wealth in terms of the real spending that the portfolio can sustain over the entire life of the obligations served by the portfolio. In 2004, we coined the expression “sustainable spending,” to gauge this true value of a portfolio.2 Jim Garland used the term “portfolio fecundity,” to describe much the same concept.3

Consider a simple thought experiment. It’s a bull market. Prices double on everything we own, while the dividend yield drops in half. Are we better off? The long-term spending that the portfolio can sustain hasn’t changed a bit. In 1997, Peter Bernstein and I4 pointed out that bull markets are actually very bad news for those who are net savers, building a portfolio to fund future needs, because it costs more to buy the same real income stream (a very crude measure of sustainable real spending5) after the bull market than before. We’re better off only if we’re spending from the portfolio immediately, not saving more for the future!

Many people felt jubilation at the peak of the tech bubble, because they felt so wealthy. And they were—as long as they were inclined to liquidate their holdings and spend before the market lost its euphoria. If they were still investing (e.g., for some future retirement), those new purchases bought precious little yield! Reciprocally, people felt panic and dismay at the 2009 trough of the financial crisis, because they felt as if their assets had been wiped out. And they were—if they intended to liquidate and spend their assets immediately. But, for the buyand- hold investor, their real income was higher than at the 2007 peak!

None of this is unfamiliar to the serious student of capital markets. So, what lessons can the thoughtful observer learn from “sustainable spending”? In the following discussion, we find bear market drawdowns have little impact on sustainable spending. Indeed, these sell-offs provide opportunities to increase our sustainable spending through disciplined rebalancing between asset classes or within asset classes, especially volatile ones like equities.

This requires courage: “no guts, no glory.”6

What is Wealth?

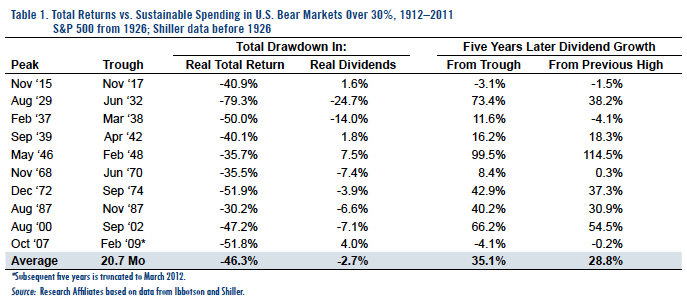

Ben Graham liked to distinguish between a temporary loss of value and a permanent loss of capital. The former is a rebalancing opportunity; the latter is a disaster. In a highly diversified portfolio where all the idiosyncratic risk has been diversified away, the latter is extremely rare. At some time during the 20th century, the stock markets of Argentina, Russia, Germany, Japan, China, and Egypt each went essentially to zero. Suffice it to say those investors had much bigger things to worry about than their stocks! Temporary losses of value are frequent; at times they can become so frightening that they become permanent—for those that sell. Through the lens of sustainable spending, these losses are far less severe. Table 1 illustrates the 10 bear markets larger than 30%, in real total return, in the past century. These aren’t as rare as most people think! The average loss is a horrific 46% real return loss (including dividends, but before taxes). Our nest egg is chopped in half, usually in less than two years. That’s awful… for anyone who wants to spend all of their money at the trough.

For those focused on the spending power of the portfolio, most of these monster bear markets were surprisingly boring. The peak to trough decline in real dividend distributions was a scant 3% drop, on average. Even in the Great Depression, real dividend distributions fell by “only” 25%. Of course, the drop was worse in simple nominal terms, because we had deflation. A 25% cut in real spending power on our portfolio, while very unpleasant, was small relative to the 80% real loss of portfolio value… and it was temporary. This 25% drop in our real spending power was the single worst outlier in a century.

On average, real sustainable spending sagged slightly during these 10 worst bear markets, then recovered massively, on average by 35%, off of their lows just five years after the market trough. In almost every case, our real distributions also achieved new highs, relative to our pre-crisis spending, besting the dividends of the previous market peak by an average of 29%! Keep in mind that this is the increase in real dividends, not just nominal payouts.

For those focused on the level of real spending, rather than the level of prices, the worst market downturns in U.S. history were mostly brief bouts of minor disappointment. The results in the recent Global Financial Crisis bear a special mention. While U.S. stocks tumbled by 51%, the real dividends distributed by the S&P 500 Index grew by 4%. To be sure, the real dividends have given up that 4% gain in the subsequent three years. But, from the perspective of spending power, these past 4½ years have been utterly boring and benign! For the buy-and-hold investor, bear markets aren’t nearly as bad as they seem. Massive market corrections disproportionately impact market prices versus spending power. But our proposed shift in our focus—drawing attention away from the value of our portfolio toward the spending power it can sustain— requires real courage: courage to ignore headlines, our brokerage statements, and our natural human instincts to sell.

Return on Courage

Now suppose we have the nerve, not only to focus on our real sustainable spending, but also to seek to increase our real sustainable spending in market downturns! If we rebalance into higher yielding assets after they’ve cratered, presumably funded from assets that have performed much better, we can systematically ratchet our sustainable spending ever higher. This ground is amply explored in asset allocation literature. Indeed, the essence of Tactical Asset Allocation (TAA) is an effort to rebalance into investments when they become most uncomfortable, and are therefore priced with a superior risk premium, to reward those who are courageous enough to invest at such times.

Even a mechanistic rebalancing policy would have compelled a trade from stocks into bonds at the peak in 2000. The trend-chasers who bought stocks at the peak, let alone buyers of high-flying growth or tech stocks, may not live long enough to be wealthier than their contrarian friends who bought ordinary Treasury bonds at that same time. They funded the success of TAA managers and strategies. Conversely, in 2009, a disciplined rebalancing strategy compelled us to buy “Anything but Treasuries.” Treasuries had dipped to the lowest yields seen in three generations. At the same time, almost anything else offered generous future spending, with many markets priced at near-record yields. Still, this was a very frightening trade.