Where Are We in the Boom/Bust Liquidity Cycle?

By Thomas Fahey, Associate Director of Macro Strategies, Loomis Sayles

March 2012

In an often cynical world, standard fi nancial and macroeconomic quantitative models give people the benefi t of the doubt. Fundamental economic theory assumes the best of us, supposing that human beings are perfectly rational, know all the facts of a given situation, understand the risks, and optimize our behavior and portfolios accordingly. Reality, of course, is quite different. While a signifi cant portion of individual and market behavior can be modeled reasonably well, the human emotions that drive cycles of fear and greed are not predictable and can often defy historical precedent. As a result, quantitative models sometimes fail to anticipate major macroeconomic turning points. The ongoing debt crisis in Europe is the most recent example of an extreme event shattering historical norms.

Once an extreme event occurs, standard models offer limited insight as to how the ensuing crisis could play out and how it should be managed, which is why policy responses can seem disjointed. The latest policy responses to the European crisis have been no exception. To understand and respond to a crisis like the one in Europe, perhaps we need to consider some new models that include the “human factor.” Economic historian Charles Kindleberger can offer some insight. In his book Manias, Panics, and Crashes, Kindleberger explores the anatomy of a typical fi nancial crisis and provides a framework that considers the impact of the powerful human dynamics of fear and greed. Kindleberger’s descriptive process of the boom and bust liquidity cycle can help shed light on the current European sovereign debt saga, and perhaps illuminate whether we have in fact turned the corner on this fi nancial crisis.

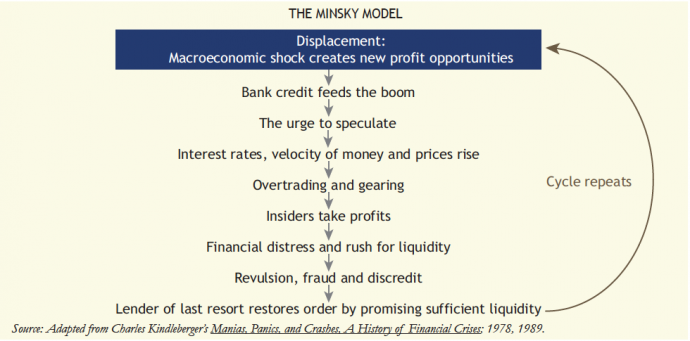

KINDLEBERGER AND THE MINSKY MODEL

Kindleberger analyzed hundreds of fi nancial crises dating back centuries and found them to share a common sequence of events, one that followed monetary theorist Hyman Minsky’s model of the instability of a credit system. Fundamentally, the more stable and prosperous an economic structure appears, the more leverage and speculative fi nancing will build within the system, eventually making it highly vulnerable to a surprising, extreme collapse. Kindleberger provided the qualitative (as opposed to quantitative!) description of the Minsky Model, shown below, which is a useful snapshot of the liquidity cycle. It can be applied to Europe and any potential boom/bust candidate, including Chinese real estate, commodity prices, or investors’ recent love affair with emerging markets. Kindleberger famously dubbed this sequence a “hardy perennial,” probably because the galvanizing human conditions of fear and greed are more often than not prone to overshoot fundamental values compared to the behavior of a rational individual, which exists only in macroeconomic theory.

DISPLACEMENT

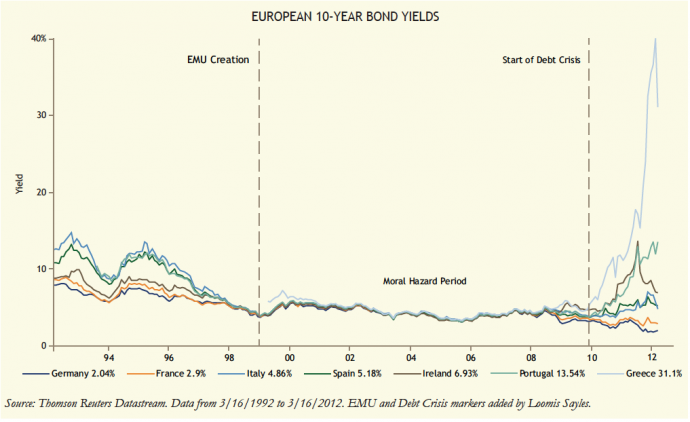

The boom typically starts with a “displacement,” a macroeconomic shock (for example a new technology, deregulation of an industry), that creates new profi t opportunities. For Europe, displacement came in the form of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) in 1999, which united participating countries under a single monetary policy and currency, the euro. By establishing one interest rate for EU member states, EMU enabled all participating sovereigns to trade as if they possessed Germany’s superior creditworthiness, regardless of their fi scal condition. The obliging market responded by lending to EU countries indiscriminately.

BANK CREDIT FEEDS THE BOOM

Armed with “AAA credit” borrowed from Germany, Europe entered the next phase of the cycle: bank credit feeds the boom. As European bond yields converged to Germany under the united currency, it appeared that Europe had entered a new era of exchange rate and interest rate stability. However, this convergence weakened market discipline and spurred mounting leverage in Europe’s public and private sectors. Money was unprecedentedly cheap for many sovereign nations and, consequently, the private sector also saw huge declines in interest rates. For example, negative real interest rates in Spain and Ireland fueled real estate booms. Europe ended up with a one-size-fi ts-none monetary policy.

Importantly, when bank credit feeds the boom, Kindleberger explains that the fi nancial system often spawns “new” forms of money. This is known as the elasticity of credit, and it facilitates borrowing and speculation. In Europe, Basel capital rules facilitated the elasticity of credit. Using the assumption that developed market sovereigns would not default, Basel capital rules had loopholes that allowed banks to hold sovereign bonds without some offsetting charge to risk-based capital. As a result, bank appetite for sovereign bonds was enduring despite deteriorating credit profi les in countries like Greece and Portugal. Without any capital charge for sovereign bonds, this created unchecked leverage on bank balance sheets.

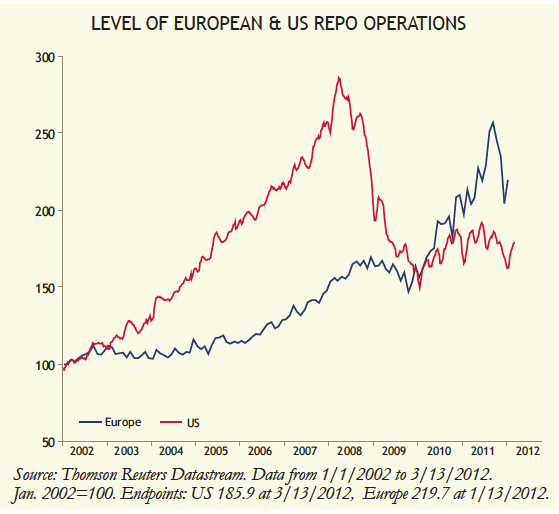

The wave of securitization and the rise of repurchase and sale (or “repo”) agreements also spawned new forms of money that fed the credit boom. The securitization and repo markets were the dark corners in which the global fi nancial crisis manifested itself, because the run on Lehman Brothers’ assets occurred in the repo market, not outside the broker-dealer’s front door. Similarly, the European banking crisis and rush for liquidity is occurring through the interbank repo markets.

The repo market, like banking, is a vehicle of liquidity transformation. Banks secure funding in short-term liquid markets, lend in longer-dated less liquid markets and collect the interest rate spread between the two. Liquidity transformation is susceptible to panics and runs if short-term lenders lose faith and demand immediate repayment. Banks have deposit insurance to limit runs, but only up to certain cash limits, say €250,0001. In the repo market, where the sums of money are in the billions, borrowers post collateral, which serves as insurance to let lenders know their money should be safe. This collateral, usually a pool of loans or bonds, allows banks to secure crucial funding liquidity through short-term loans.

Securitization and the repo market expanded the elasticity of credit that fed the boom. In a circular fashion, they also increased the demand for eligible collateral to post as insurance in the repo market. This is where the fi nancial engineers went to work and helped create AAA collateral out of worthless loans to subprime borrowers. By not requiring capital charges on sovereign bonds, the laissez-faire regulatory environment also made sovereign bonds highly valued collateral in repo transactions.

SPECULATION, OVERTRADING & GEARING

As the cycle churned on, the urge to speculate in sovereign bonds, real estate and structured products drove prices higher, and the velocity of money (rate at which money changes hands) expanded. This is typical of booms—easy credit and the increased wealth that accompanies soaring asset valuations feed a sense of euphoria and the perception that asset values will increase indefi nitely. Greed enters. In Europe, private and public investors were riding high. They willingly suspended their disbelief, seduced into thinking the music would never stop. Liquidity transformation, especially in the repo market, tends to be very pro-cyclical. As long as prices rise and collateral values remain stable, there is ample market-based liquidity to fuel the overtrading and gearing (leverage) of assets. It was circumstances like these that led Irish banks to lend against questionable assets six times the size of the nation’s economy without being questioned. According to Minsky’s fi nancial instability hypothesis, this is the time when the fi nancial system starts becoming highly speculative and shaky despite the appearance of stability. Just look at how stable European bond yields were before the crisis, hiding deeprooted credit problems in the peripheral markets.

INSIDERS TAKE PROFIT AND THE RUSH FOR LIQUIDITY

Finally, the cycle grinds to the point at which insiders start to take profi ts, precipitating a rush for liquidity. Insiders are investors who possess an information advantage—and they represent a powerful reality that fl ies in the face of economic theory and modeling. If insiders or lenders begin to worry that the collateral pool (of sovereign bonds, bank loans, structured products) is weakening, they can demand better collateral or a bigger haircut (the difference in value between the actual money lent versus the posted collateral). These increased requirements compromise borrowers’ ability to fund their liquidity transformation, fear unseats greed, and the panicked rush for liquidity is on. Borrowers are forced to sell assets and reduce leverage, causing prices to abruptly reverse.

The fact that transactional money (or market-based liquidity) and credit (like the repo market) are not factored into traditional economic models is a critical reason why these models failed to identify the severity of the global fi nancial crisis or its reverberations throughout the interconnected fi nancial system. It was in the repo market that the insiders fi rst began to take profi ts during the European sovereign and banking panic of 2011, just as they had done three years earlier when Lehman Brothers imploded. As shown in the chart to the right, during the summer and fall of 2011, the level of repo reported by the Federal Reserve and European Central Bank (ECB) was declining, signaling insiders’ stress and the rush for liquidity. Though most traditional models may have missed the signs of speculative fi nance and growing instability, the Minsky Model helps highlight these risks, at least fi guratively.

REVULSION, FRAUD, DISCREDIT AND THE LENDER OF LAST RESORT

Once the liquidity reverses, causing a fi nancial crash and crisis, the fi nger pointing begins. Heroes turn to villains as revulsion, fraud and discredit creep in. Banker revulsion has become an enduring issue, the Greek fraud as to the true size of its national debt has been disclosed, and the notion that a developed market sovereign could not default was discredited. The saga has followed the typical sequencing of a fi nancial crisis, but a critical question remains: have we moved past revulsion, fraud, discredit and turned the corner toward recovery?

According to Kindleberger’s fi gurative description of Minsky’s liquidity cycle, we should be turning the corner on the bust phase of the global liquidity cycle because lenders of last resort have fi nally promised suffi cient liquidity to restore order—or have they?

In our previous updates on the European crisis, we were very critical of the ECB because it was, in our view, not acting like a credible lender of last resort. There was a rush for liquidity when the European repo market plummeted in the fall of 2011. Widening credit spreads, falling equity prices and tighter bank credit indicated the markets were screaming for liquidity. At that time, we believed that the ECB needed to expand its balance sheet much more aggressively and meet the rising demand for liquidity. The ECB has since responded, and its balance sheet is expanding rapidly. Most recently, the ECB broke the fever of risk aversion with its three-year Long-Term Refi nancing Operation (LTRO), which delivered liquidity to the banking system and should help avert the development of a severe credit crunch.

While central bank liquidity buys time, it does not fi x the fundamental solvency question of whether there is enough future income to service outstanding debts. The saying “a rolling loan gathers no loss” is a nice thought, but eventually bad debt has to be recognized, and someone has to take a loss. The gearing, or leverage, from the past decade’s credit boom was massive and is taking a long time to resolve. It takes time to reveal which assumptions on future income, prices and profi tability levels were faulty when leverage was rising rapidly. Recent information on some European balance sheets, including the Greek sovereign balance sheet, has revealed such extreme gearing that it is unrealistic to think future incomes and tax revenues will be suffi cient to service the debt. For now, policy makers are trying to fortify balance sheets before recognizing any potential losses to minimize systemic risks. In our view, we are not through the process of unwinding leveraged balance sheets; that is why we have had such a hard time reaching escape velocity from the fi nancial crisis despite repeated attempts by central banks to provide suffi cient liquidity. The halting economic recovery suggests central banks will have to fi ght any urge to prematurely reduce their unconventional liquidity provisions.

Nevertheless, the fact that the ECB has laid its cards on the table and is acting like a lender of last resort, despite its tough rhetoric, is good news. Other central banks have also moved to provide more liquidity: the Federal Reserve, for example, recently gave guidance that interest rates will stay very accommodative until late 2014; the Bank of Japan has implemented an infl ation goal of 1.0% and will use quantitative easing to pursue its objective; the People’s Bank of China cut its capital reserve requirements and has been rolling loans to local governments; the Brazilians, Australians, Swedes and Norwegians all cut interest rates. Coordinated central bank actions are helping to boost risk appetites globally. These are positive signs for reducing major systemic tail risks going forward.

So, if central banks are trying to restore order by promising suffi cient liquidity, should we now focus on identifying where bank credit could feed the next boom? Our answer is a resounding yes. The next boom always seems to rise from the ashes of the previous bust, just as the global housing bubble rose from the easy money policies that followed the 1990s technology bust. For now, investors should look around the world and determine which banking systems appear healthy enough to provide that elasticity of credit. In many developed markets, there are still major headwinds to a traditional borrowing- and spending-driven recovery. The consumer and public sectors appear less willing or able to leverage their balance sheets to provide that extra boost to growth. Emerging markets, on the other hand, should still have ample room to grow. However, we suggest investors remain vigilant, watching for any sign that booming credit has sown the seeds of Kindleberger’s “hardy perennial.”

Charles P. Kindleberger (1910-2003) was an American economist and economics professor. His noted works include Manias, Panics, and Crashes, A History of Financial Crises, first published in 1978 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.).

Hyman P. Minsky (1919-1996) was an American economist and economics professor. His noted works include Stabilizing an Unstable Economy, first published in 1986 (Yale University Press).

Past market experience is no guarantee of future results.

This article is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice. Any opinions or forecasts contained herein reflect the subjective judgments and assumptions of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect the views of Loomis, Sayles & Company, L.P., or any portfolio manager. Investment recommendations may be inconsistent with these opinions. There can be no assurance that developments will transpire as forecasted and actual results will be different. Data and analysis does not represent the actual or expected future performance of any investment product.

We believe the information, including that obtained from outside sources, to be correct, but we cannot guarantee its accuracy. The information is subject to change at any time without notice.

MALR008968 LEGREV122812

Copyright © Loomis Sayles