‘My’ list of new technologies is the result of a several weeks of research but is by no means complete (I would welcome any emails with opportunities that I have failed to mention). Please also bear in mind that I am an economist, not an engineer, so don’t harass me if I occasionally use technically incorrect terminology. Stay focused on the big picture!

Extreme fuel efficiency

Earlier this year, at the Qatar Motor Show, Volkswagen unveiled a remarkable new car called the XL1 (see pictures here and more details about the car here), which is expected to go into limited production as early as 2013. The car runs on a 0.8 litre hybrid engine (combined TDI engine and lithium battery) capable of carrying two people at a top speed of 160 km/h (100 mph).

The XL1 can drive an astonishing 110 km/l (313 mpg) and emits only 24 g/km of CO2 in the process. As an added bonus, the car can do up to 35 km (22 miles) in battery mode, i.e. with zero carbon emissions. A lightweight body of only 795 kg partly explains the impressive performance. The car has been 13 years in the making and is by far the most fuel efficient car the world has seen to date.

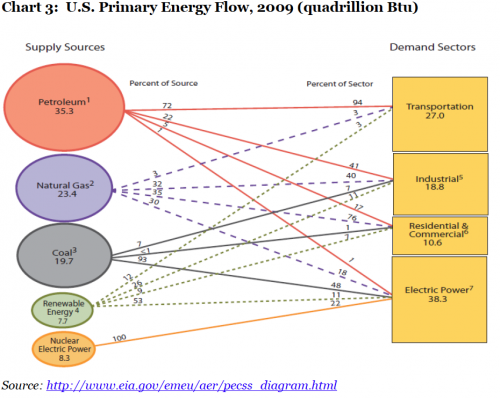

Now, let’s imagine for a moment that every private car in America could run 110 km/l (260 miles per U.S. gallon). The almost 300 million people in the United States go through approximately 20 million barrels of crude oil every day. 72% of that, or approximately 14 million barrels, go towards transportation (see chart 3).

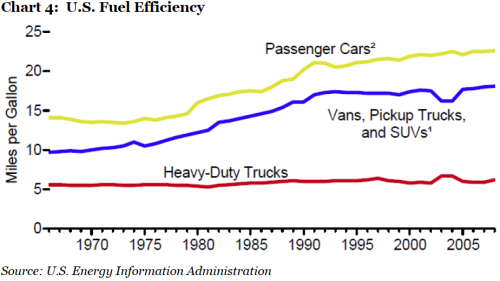

Of those 14 million barrels, 8.5 million are turned into petrol each and every day. Most of the rest is used for diesel and aviation fuel. Now let’s assume that all private cars on American roads use petrol - not an unreasonable assumption, as few private drivers in America have taken a liking to diesel. Let’s also assume that the average private car in America does about 20 mpg (seems reasonable given chart 4 below).

If every private car, SUV and pick-up truck in America could do 260 mpg (which of course is completely unrealistic in the short to medium term), the 8.5 million barrels per day of crude oil used by private drivers could be reduced to less than 1 million bpd, equivalent to over $300 billion of annual savings, or 2% of GDP.

The point I want to make is not that this is necessarily going to happen anytime soon, but that it is in fact extremely easy to dramatically reduce the consumption of crude oil in the United States today, so long as there is a political will to do so.

If you then carry on the same thought process, assuming that the rest of the world is twice as fuel efficient as the U.S. economy, a quick back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that daily oil consumption in the rest of the world could be reduced by 18-20 million bpd in addition to the 7-8 million saved in the U.S.

Now, a two-seater is not an appropriate car for every Tom, Dick or Harry. Mums on school runs, taxi drivers and bigamists are amongst those with different needs but, based on the number of cars I see every morning with one person in them going at 30 mph (at best) through London’s congested rush hour traffic, there should be a significant market for a car such as this one. Let’s say for argument’s sake that a two-seater would suffice for one-third of all drivers in the world. Oil consumption could then be reduced by 8-9 million barrels per day in one swoop, not to mention the dramatic reduction in CO2 which would follow.

It is probably also fair to say that to many, a two-seater hybrid which can ‘only’ do 0-100 km/h (0-60 mph) in 11.9 seconds would be a step down relative to the gas-guzzler they currently drive (I include myself in this category), but this is where political leadership and, if necessary, legislation comes in. The EU has recently decided to ban all conventionally fuelled cars from city centres across the EU beginning in 20503. The decision raised the predictable storm of protests, but the key is in the wording. Cars will not be banned altogether, only those using conventional fuels.

Hydrogen

Improved fuel efficiency is by no means the only way forward. Hydrogen has been on the radar screen for years as a possible future source of transportation fuel, but the dangers involved in the handling process have meant that highly sophisticated equipment (high pressure tanks) were required to make it safe. Now that problem appears to have been overcome – a new technology developed by a UK company called Cella Energy allows users to pour hydrogen into the car’s fuel tank in very much the same way as we pour petrol into our cars today4.