by Luis AV Catão, and Roberto Chang, via VoxEU.org

Rising food prices once again pose central banks a tricky question. How far should they ignore food price inflation? This column suggests that food tends to have stronger predictive power on global inflation cycles than oil. The problem is more severe in emerging markets where consumption basket weights for food are two or three times larger than in rich nations. Central banks should pay close attention.

The uneven recovery in advanced countries is hiding an issue that, while off the agenda in the last G20 meeting back in November, is arguably no less urgent for the global economy – namely, the rise in food prices.

- Following a steep acceleration initiated last summer, global food prices (as measured by the IMF global food price index) rose by 21% in the year leading up to November 2010 (latest available figure).

- Global average food prices are now back to their pre-crisis peak, despite a collapse in the wake of the 2008/09 financial crisis,

Coupled with the most recent round of weather setbacks and slashes in key crop forecasts worldwide, there is little hope that such inflationary pressures will abate. If anything, the US and EU economic recovery will exacerbate them.

In advanced countries, these developments have not yet percolated through the inflation outlook, which remains broadly dormant due to offsetting effects of falling manufacturing prices and continuing slack in labour markets. But this isn’t so elsewhere.

- In emerging markets, non-trivial deviations from targeted inflation have begun to emerge.

- Food price sub-indices are well ahead of headline inflation, often two to three times as fast.

This is particularly alarming insofar as much of the acceleration in food inflation in emerging markets comes from basic staples such rice and corn, with seemingly limited scope for substitutability in consumption baskets.

In Indonesia, for instance – where per capita rice consumption is higher than the Asian average – rice prices were up by as much as 30% in the year to December. Subsidies and tariffs, meanwhile, have mitigated the external price pass-through only to a limited extent elsewhere in the continent. From Jakarta to Mexico City, stories of rising imports making up for significant shortfalls in the domestic supply of such staples continue to abound.

With food typically weighing 20% to 50% in national consumption baskets in developing countries, as opposed to 12% to 15% in core advanced countries (see Table 1), this “decoupling” in the inflation outlook is hardly surprising. But it does not make the issue of global food inflation any less critical looking forward.

While longer-term price projections for some these staples portray a bright picture for many emerging markets in terms sustainable terms-of-trade gains over the current decade (OECD-FAO 2010), the ongoing acceleration in food prices creates important dilemmas for monetary policy in net food exporters and importers alike over the near term.

Food inflation more important than oil price rises

History is adamant on the risks. While much has been made of oil prices as drivers of global inflationary spurts since the 1970s, recent work of ours (Catão and Chang 2010) provides evidence that food price pressures have been no less important. The data in fact suggests that food tends to have stronger predictive power on global inflation cycles than oil.

As Figure 1 illustrates, every single inflation upturn over the past four decades has been preceded (with a one to two-year lag) by an uptick in world food prices; this causality relation is confirmed by formal econometric tests. To be sure, one could arguably blame such past slippages on the looser monetary regimes of the 1970s and 1980s. Yet, later experience indicates that this transmission mechanism remains quite alive in the more recent era of inflation targeting too.

This is portrayed in Figure 2, which plots the IMF global indices of food and oil prices (measured along the left vertical axis) against the cross-country median of percentage deviations from the central inflation targets (measured along the right vertical axis) for all countries that have formally adopted inflation targeting. Clearly, the large swings since 2006 in deviations of actual from targeted inflation have coincided with attendant swings in world food prices. Further, Figure 2 also confirms that food prices are better predictors of global inflation than oil prices. While oil prices began to climb up in earnest from 2003, significant deviations from targeted inflation only materialised after food prices took off from late 2006. In short, there is substantial evidence – both recent and well-past – that food prices lurk behind large international swings in inflation rates.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Against this background, a key question to national central banks is the extent to which such imported inflation should be accommodated. In the case of large central banks like the ECB and the US Federal Reserve, two considerations stand out.

- The first is that their actions have a direct bearing on global food price given their weight in world income and capacity to set world interest rates, influencing food prices via both demand and supply channels.

- The second is that their actions have strong externalities elsewhere. In the emerging/developing world, this can be far-reaching because food accounts for a very high share in consumer spending and, since much of it consists of non high-end items, it cannot be substituted away.

Well-known structural weaknesses of developing countries add to the problem. Soaring food inflation can trigger far-reaching unrest wherever political institutions are fragile, financial systems are less mature to smooth out shocks, and social safety nets inadequate, as witnessed by the many food-related riots during 2007-08.

What should monetary policy do?

A situation that deserves special consideration is that of the worst sufferer – the price-taking small-open economy that is a net food importer with a share of food in the national consumption basket far larger than that of the advanced world. In that case, our work (Catão and Chang 2010) indicates that monetary authorities should not accommodate the attendant rise in CPI inflation even if they do not practice price level targeting. In fact, among the policy rules usually adopted by central banks, the strict targeting of broad CPI inflation is often the best for domestic welfare.

In other words, setting monetary policy on the basis of CPI inflation stripped from its commodity price sub-indices, or targeting domestic producer inflation, is less advisable. This is so because CPI targeting strikes a better balance between stabilising the real exchange rate, which in turn helps stabilise domestic consumption, and keeping domestic producer inflation under control without over compressing it.

The reason it is desirable to stabilise domestic producer costs (and hence prices) is that not all producers in this small open economy are free to set prices at any moment, which distorts relative prices across producers, which is sub-optimal. This is more critical the more persistent the food price shocks; and the empirical evidence suggests that such shocks are typically very persistent.

Completely stabilising domestic prices, however, is not desirable because it robs some latitude from domestic producers, given imperfect international arbitrage in goods markets, to raise prices, which will be partly paid for by the foreign consumer. Allowing domestic prices to be set a bit higher on average as a reaction to volatile food prices (and hence to volatile wages and costs), the small-economy policymaker makes more effective use of the so-called “terms of trade externality”.

Finally, as greater real-exchange-rate stabilisation also helps stabilise the purchasing power of food-intensive consumption baskets, the distributive consequences of CPI inflation targeting are less dire than those of producer price inflation targeting. This is particularly relevant for countries with highly skewed income distribution and inadequate social safety nets. So, as with some of the literature on oil price shocks (see e.g. Batini and Terenu 2010; Blanchard and Gali 2007 and references therein), the above considerations make a case for a non-accommodating policy stance toward imported food inflation.

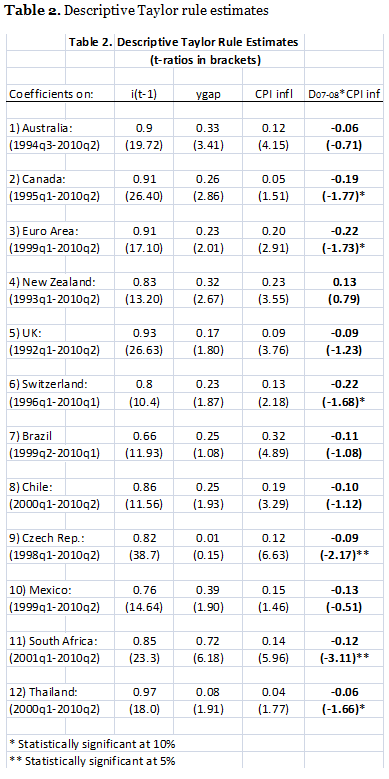

Yet, judged by standard estimates of the Taylor rule, strict adherence to broad CPI targeting appears to have been the exception and not the rule during rampant food inflation in 2007-08. To the best of our knowledge, this observation has not gained due currency in policy circles and/or among market observers and, yet, is readily apparent.

Table 2 reports regressions of the policy interest rate on its first-order lag, the HP-filtered output (“ygap”), and on current CPI inflation (“CPI inf”). Because central inflation targets move over time in some countries, both the interest rate and the inflation rate are measured as deviations from the central inflation target. Finally, the set of explanatory variables includes the interaction of inflation with a dummy which equals 1 during the food price hike of 2007Q1-2008Q3 and zero otherwise. A negative coefficient on this interaction term indicates that policy rates were set lower in 2007Q1-2008Q3 than they should have been, relative to the average reaction. That coefficient is negative in all Table 2 countries except New Zealand; it is also statistically significant at 10% or less in half of them. This is all the more surprising in light of evidence that food price shocks tend to be highly persistent and that monetary policy operates with long lags, particularly in advanced countries. One might expect these two considerations to trigger a more prompt and aggressive response to the 2007-08 hike.

This apparent leniency in individual policy responses – at least when measured relative to standard Taylor rule baselines – had global implications. World real interest rates would otherwise have been higher, which in turn would have helped dampen commodity prices and possibly contain the widening in global imbalances. Higher world interest rates at the onset of the crisis would also have given central banks more latitude for subsequent easing, possibly obviating widespread resort to heterodox measures like quantitative easing.

Policy lessons

Going forward, what lessons can we take from this evidence?

- First and foremost, global food price pressures pose a sizeable threat to global monetary stability.

- Second, they pose an externality problem that demands non-trivial coordinated action by key central banks.

Left alone, we should fear that coordinated action may come in too little and too late because the inflation spillovers are largely felt first in emerging markets (again, much due to higher food shares in consumption baskets) and because individual advanced societies are better equipped to withstand such a price shock at least for a while. So, the associated policy prescription is hardly “one-size-fits all”. These various considerations suggest that strict and widespread targeting of broad CPI inflation, while not a silver bullet, does help.

To be sure, the more aggressive interest rate reaction to imported food inflation demanded by broad CPI inflation targeting raises well-known problems of its own for the small open economy, particularly regarding capital inflows. Standard macro models featuring complete international capital markets and frictionless domestic financial intermediation are ill-suited to address these problems. While developments in this area of research are promising, they still fall short of offering clear-cut prescriptions to policy makers. Absent that, the targeting of broad CPI inflation, when consistently implemented, appears to be a stronger contender than other rules in terms of mitigating monetary policy externalities on a global basis and helping keep global inflationary pressures at bay.

The views expressed in this article are the sole responsibility of the authors and should not be attributed to the International Monetary Fund, its Executive Board, or its management.

References

Batini, Nicoletta and Eugene Tereanu (2010), “Inflation targeting during asset and commodity price booms”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 25:15-35.

Blanchard, Olivier and Jordi Gali (2007), “The macroeconomic effects of oil shocks: why are the 2000s so different from the 1970s”, NBER Working Paper13368.

Catão, Luis AV and Roberto Chang (2010), “World food prices and monetary policy”, NBER Working Paper 16563.

OECD-FAO (2010), Agricultural Outlook 2010-2019, Paris.

Copyright (c) VoxEU.org