by John Hussman, Hussman Funds

Why are Treasury yields rising despite hundreds of billions of Treasury purchases by the Federal Reserve? There are two possibilities in the current debate. One is that the Fed's policy of purchasing Treasuries has scared the willies out of the bond market on fears of higher inflation, and that the policy is a failure. The other is that the policy has been such a success at boosting the prospects for economic growth that interest rates are rising on anticipation of a better economy.

From our standpoint, neither of these explanations hold much water. On the inflation front, the recent bond selloff has hit TIPS prices as well as straight Treasuries, which isn't something you'd expect to see if inflation expectations were being destabilized. And although precious metals and other commodity prices have been pressed higher, the commodity run can be more accurately traced to negative real interest rates at the short-end of the maturity curve, coupled with a downward trend in long-term yields that has now reversed dramatically (more on that below). I've long argued that unproductive government spending and profligate fiscal policy are ultimately inflationary (regardless of how the spending is financed, and particularly if it is monetized), but I continue to view persistent inflation as a long-term, not near-term concern. A rise in T-bill yields of more than 15-25 basis points would change that assessment. Until then, velocity can be expected to collapse in direct proportion to changes in the monetary base, with little impact on prices.

As for the notion that the Fed's targeted Treasury purchases have directly aided the economy, the argument requires bizarre logical gymnastics. It demands one to believe that although the purchases were intended to stimulate the economy by lowering rates, they have been successful without lowering them, and in fact by raising them, because the expectation of lower rates was so stimulative that it caused rates to rise, so that the higher rates can be taken as evidence that lowering rates without lowering them was a success. Oh, brother.

It's clear that we've seen some firming in various indicators such as the Purchasing Managers Index, the ECRI Weekly Leading Index and weekly claims for unemployment. The question is whether these can be traced to lower yields and greater availability of liquidity. On the interest rate front, the answer is clearly no, as Treasury and mortgage rates are even higher than they were before QE2 was announced. On the "liquidity" front, the additional reserves have simply added to an existing pile of well over a trillion dollars of idle reserve balances in the banking system. And while we did see a pop in consumer credit in the latest report, it was entirely due to Federal loans to students (arguably people displaced from the labor force and seeking an alternative). Other forms of consumer credit have collapsed at an accelerating rate.

So neither side typically taken in the debate over the Fed's Treasury purchases is particularly satisfying. Fortunately for fans of logic, there is a third explanation that is much more plausible, and has the benefit of having data behind it. Despite my extreme criticism of Fed actions in recent years, I would argue that QE2 has in fact been "successful" over the short-term, but not through any monetary mechanism. Rather, QE2 has been successful a) by creating a burst of enthusiasm that released some pent-up demand in the same way that Cash for Clunkers and the new homebuyer tax credit did, and b) by encouraging investors to believe that the Fed has provided a "backstop" for stocks and other risky assets, creating a speculative blowoff in these securities, to the detriment of what investors perceive as "safe" assets, which ironically includes Treasury securities.

In short, the main effect of QE2 has not been monetary but has instead been rhetorical - and that rhetoric may very well be nearly empty.

The key event related to QE2 wasn't its formal announcement, but was instead the Op-Ed piece that Ben Bernanke published a few days later in the Washington Post, which essentially advanced the argument that the Fed was targeting a "wealth effect" in stocks and other risky assets, in hopes of getting people to consume off of that perceived wealth. At that moment, Bernanke unleashed a speculative bubble in risky assets, and a selloff in safe ones. This has rewarded risk-seeking and punished risk-aversion, but it has also unfortunately driven the markets into an overvalued, overbought, overbullish, rising-yields condition that has historically ended in steep and abrupt losses.

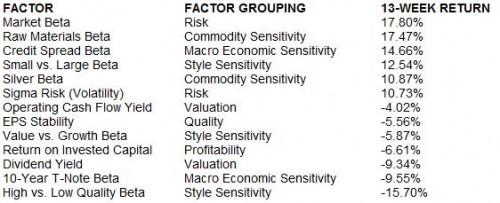

Ned Davis Research tracks a set of "factor attribution" portfolios, which measure the performance between the top 10% of stocks ranked by a given factor, and the bottom 10% of stocks as ranked by that factor. The factors are things like market beta, dividend yield, 26-week momentum, and so forth. Essentially, the these factor portfolios track the return of hypothetical portfolios that are long the top 10% and short the bottom 10% of stocks based on any given variable.

The performance of these 133 factor portfolios over the past 13 weeks offers tremendous insight into the extent to which the Federal Reserve has encouraged speculative risk. Investors are chasing stocks with the greatest exposure to market fluctuations, commodities, credit risk, small-cap risk and volatility. Conversely, securities demonstrating reasonable valuation, stability, quality, or payout have been virtually abandoned by investors. Here is a sampling:

For us, the past few months have felt like our own miniature equivalent of a bear market. The Strategic Growth Fund has pulled back by several percent, and though our occasional drawdowns have been a fraction of those experienced by the S&P 500 over time, the past four weeks have felt relentless on a day-to-day basis. During this period, the strongest four factors have been: Market Beta (8.98%), Sigma Risk (8.50%), Small vs. Large Beta (8.05%), and Cyclical vs. Consumer Beta (7.75%). Meanwhile, factors such as High vs. Low Quality Beta (-2.18%), Dividend Yield (-3.07%), and EPS Stability (-5.16%) have been particularly unrewarding.