by Carl Tannenbaum, Asha Bangalore, Northern Trust

There was a time when the heads of the world’s major central banks were treated with the reverence afforded a head of state. Their every utterance was taken as gospel and their appearances among commofners inspired adulation. Governments recruited widely for the best candidates and held onto them dearly once secured. All of this was well-warranted: central bankers were periodically called fupon to save the world.

Today, central bankers are being treated rather shabbily. Politicians feel freer to criticize monetary authorities and seek deeper influence over their affairs. Parliaments that contributed to crises and proved effete in their reactions are now shifting the narrative, blaming central banks for laxity in advance and overreach thereafter. Amid the attacks, the heads of the Bank of England (BoE) and the Federal Reserve were recently reduced to insisting that they would stay on for their full terms.

Pendulums shift, and so does public opinion. But recent proposals go beyond second-guessing to advocate a significant shift of power from monetary to fiscal authorities. With global politics in considerable flux, though, independent central banks may be more essential than ever.

Control over the financial printing press has been a controversial topic since the beginning of commerce. Governments, populated by members with short election horizons, often prefer stimulus to restraint to curry favor with voters. Prospective consequences of easy money (like inflation and inflated asset prices) may not appear for some time and can therefore be set aside until after the balloting.

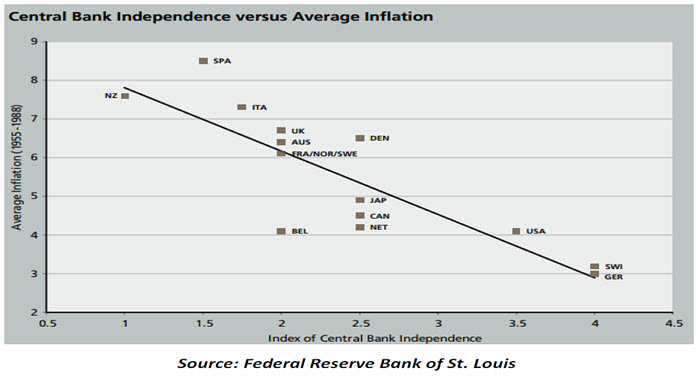

Properly structured, a central bank can take the long-term view that counterbalances this orientation. Terms for central bankers are typically quite long, providing room to make decisions that may initially be unpopular. Academic studies have shown that countries with more independent central banks have lower rates of inflation.

Central bank independence has never been absolute. At many times and in many places, central banks have been considered wings of the government. The Fed was the third attempt at establishing an independent central bank in the United States, the first two having been eliminated by the political establishment. The Fed itself spent a good portion of its history coordinating closely with the Treasury Department.

In Europe, the BoE did not become independent until 1997. The formation of the European Central Bank (ECB) represented a loss of monetary sovereignty for member nations, and its design only emerged from delicate negotiations.

To bolster their efforts, monetary authorities play a leading role in bank supervision. Supporters contend this arrangement provides a feedback loop of economic intelligence.

Detractors fear central banks might modulate their level of financial oversight to advance their economic objectives, which could open or close the lending spigots at the wrong time.

Detractors fear central banks might modulate their level of financial oversight to advance their economic objectives, which could open or close the lending spigots at the wrong time.

The wrestling match between these two perspectives has created a complicated global web of financial oversight. It catches a good deal of misbehavior, but has demonstrated some gaps as firms seek the most lenient treatment. Since 2009, steps have been taken to position central banks to be more comprehensive overseers.

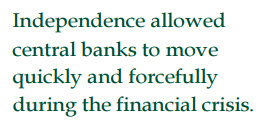

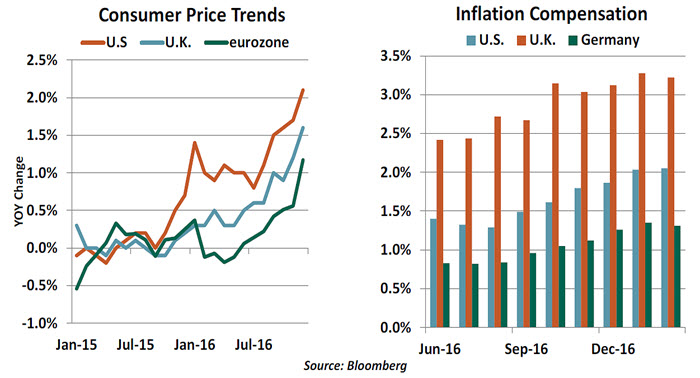

The powers held by central banks were essential to the recovery from the financial crisis. Aggressive monetary stimulus compensated for limitations on the size and speed of fiscal reaction. And supervisors engineered the rehabilitation of the financial industry. But crisis-era strategy has remained in place for a very long time. Today, inflation and inflation expectations are rising, and the Fed, the BoE, and the ECB have all been accused of remaining too accommodative for too long.

The BoE has come under particularly harsh criticism. Its governor, Mark Carney, reduced rates and reintroduced quantitative easing after the Brexit vote last June in an effort to stabilize sentiment and pre-empt adverse reactions. The British economy has performed very well since then, perhaps surprisingly so. But instead of giving Carney credit for this outcome, observers have criticized him for doing the unnecessary.

Prime Minister Theresa May said last fall that low interest rates have had “some bad side effects,” referring to the impact on savers. May added, “A change has got to come. We are going to deliver it.” While the U.K. government and the Bank of England have since denied any dissonance, the tension between them may grow as Brexit negotiations create new uncertainties.

President Mario Draghi of the ECB has also found himself in an unexpected bind. Growth in the eurozone has been quite good over the past year, exceeding official projections. Recovering oil prices have pushed the price level higher, leading some to suggest an end to monetary accommodation. But Draghi’s work is far from complete. There remain huge differences in economic performance across Europe, and the banking system is far from sound. The potential for disruption from Brexit and upcoming European elections remains significant. This is not the time to taper.

Draghi has been demonized by Europe’s populists, placed among the symbols of all that is wrong with European integration. He is equally controversial in Northern Europe for his willingness to indulge poor economic behavior in peripheral countries. His term extends for two more years, but thoughts of his Roman home must occasionally run through his mind.

Both Carney and Draghi see themselves as counteracting the paralysis in European governance. Monetary policy may not be the right tool for the job at hand, but it is the only tool if national leaders embrace fiscal austerity and avoid structural reform. It must be challenging for them to receive criticism from those whose failings have contributed to their difficulties.

Back in the United States, the Fed is also under fire. Janet Yellen invested two days in front of the U.S. Congress this week, where she faced sharp questioning over her handling of the economy. Interest rates (too low) and regulation (too much) seemed to be the main concerns.

Back in the United States, the Fed is also under fire. Janet Yellen invested two days in front of the U.S. Congress this week, where she faced sharp questioning over her handling of the economy. Interest rates (too low) and regulation (too much) seemed to be the main concerns.

The White House and Congress may soon have a bit more influence in both areas. The resignation of Fed Governor Daniel Tarullo will remove a dovish voice from the interest rate debate and will create a third opening on the Fed’s Board of Governors. At least one nomination can be expected soon, and it will send an important signal.

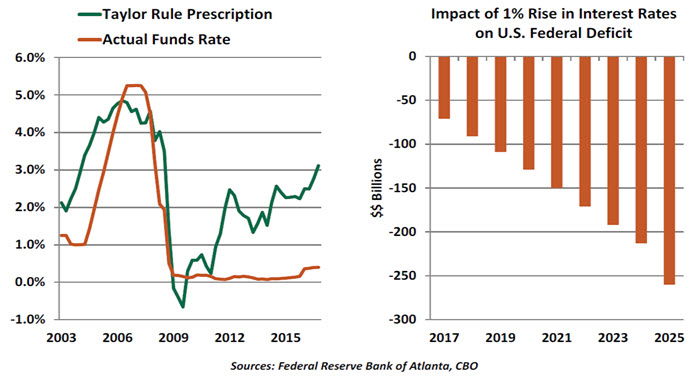

There are many in Washington who would prefer a more restrictive and predictable approach. The Taylor Rule, one expression of this spirit, suggests that interest rates should be much higher than they are today. But the country is indebted, and rising interest rates would certainly put a damper on fiscal ambition.

Does Donald Trump want higher rates, or lower rates? We may soon find out.

Tarullo has also served as the Fed’s point person on bank regulation. He has pressed successfully for improved levels of capital and liquidity in the financial system. But those efforts have also made financial institutions less profitable, and many bank executives have been salivating at the chance to initiate a retreat. But allowing greater leverage in the economy might not be the greatest idea at the moment, especially since a series of asset markets look richly valued.

Central banks are not infallible, and for that reason, they are subject to many checks and balances. But central banks need to maintain a certain distance from governments to serve as an effective check on their activities. Let’s hope that the two don’t get too close for comfort.

Wise Council

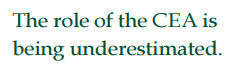

The U.S. Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) has traditionally played a significant role within the White House, providing an impartial and in-depth take on the economic impact of prospective policy choices. Today, however, the CEA is in some peril. Without it, the administration may be left trying to navigate a complex economic landscape without a compass.

President Truman established the CEA as part of the Employment Act of 1946, motivated by lingering fear of the Great Depression and the view that government deficit spending could stabilize the economy during severe economic stress.

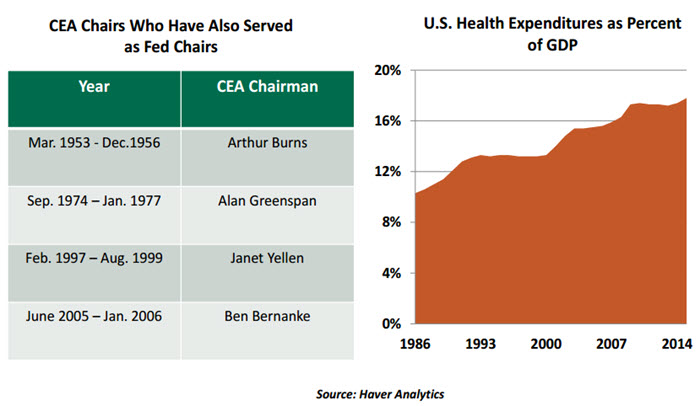

The CEA is comprised of a chairman and two other members, appointed by the U.S. president and confirmed by the Senate. The chair of the CEA is essentially the chief economist in the White House. Leading the council is a prestigious assignment; several heads of the CEA have also led the Fed.

President Trump recently announced that the chairman of the CEA would not be a part of his cabinet. No one has yet been named to the council, and there seems to be no timetable for the appointments. There are concerns that the CEA may be eliminated altogether.

This would be a grave mistake. There are a number of important economic policy changes currently under consideration. At the top of the priority list are health care, tax reform, infrastructure spending and trade. Input from the CEA will be essential to making good choices in each of these areas.

This would be a grave mistake. There are a number of important economic policy changes currently under consideration. At the top of the priority list are health care, tax reform, infrastructure spending and trade. Input from the CEA will be essential to making good choices in each of these areas.

Health care expenditures account for nearly 18% of U.S. GDP, and they are projected to scale new heights during the next decade. Health care is a politically sensitive issue, with significant fiscal implications. An essential part of the discussion is the evolution of health care costs under various policy alternatives.

Tax reform and infrastructure spending will alter the nation’s debt trajectory. A complete understanding of the repercussions of these changes is required before undertaking them.

Tariffs on U.S. imports of goods and services will affect inflation, monetary policy, and potentially trigger retaliation by trading partners. These eventualities will affect employment and result in a host of other ramifications that need to be examined in detail.

To make an informed decision on these matters, the president needs personnel to assemble, organize, analyze and present a range of relevant economic and financial data. The analysis is essential to understanding the consequences of different choices. This task requires a thorough grounding in economic theory, economic modeling and institutional arrangements.

The CEA exists to address these demands. The office of the CEA traditionally follows a strict professional standard and has maintained an outstanding level of objectivity, critical attributes in an environment where numerous ideas are constantly presented to the president. An independent body that is an analytical check is imperative for sound policy choices. Finally, the annual “Economic Report of the President,” a comprehensive report analyzing the major economic developments shaping the U.S. economy, is one of the CEA’s key publications. When I began my studies in the U.S., this report was my guide to the U.S. economy, and I still consider it useful.

There are several instances when presidents have disagreed with the CEA and implemented policies that differ from the CEA’s recommendations. But the president needs quality guidance and advice in evaluating far-reaching economic policy changes. The existence of the CEA for more than 70 years is a testament to its usefulness as a better conduit than partisan sources for economic analysis. We hope that this president ultimately agrees with us, and moves quickly to staff the council appropriately.

Copyright © Northern Trust