by Corey Hoffstein, Newfound Research

This blog post is available as a PDF here.

- Many articles expounding upon the risks of ETFs that invest in illiquid assets (high yield bonds, bank loans, emerging markets, etc.) have been published in recent years.

- While there are additional risks inherent to these ETFs, the ETF structure provides an additional layer of liquidity that is not available when trading directly in the underlying securities. With the majority of trades in an ETF, the underlying assets are never even traded.

- When markets lock up or assets do not trade, price, which is used in calculating NAV becomes an illusion. ETFs allow investors to trade based on the value of the underlying securities as the ETF price deviates from the stale NAV.

- The additional liquidity and price discovery are key benefits to investing in illiquid assets through an ETF as opposed a mutual fund.

There was yet another article published this week about the liquidity threat of fixed income ETFs. The article, published by Bloomberg, was titled Pension Fund’s Liquid Gold and specifically discussed the use of high yield bond ETFs as a liquidity sleeve in pension fund portfolios.

Liquidity sleeves are often employed when a portfolio manager wants to retain exposure to a given asset class, but does not necessarily want to perform individual security selection or has yet to find an adequate active manager to allocate to.

Despite this interesting bent to the story, the article rapidly converges back to the same thread of critique we’ve heard consistently over the years: the disparity between the speed at which high yield bond ETFs trade (milliseconds) and the speed at which high yield bonds trade (often over the phone) is dangerous.

Dangerous how? There are really two unique concerns people bring up.

The first is, “could a panic among ETF investors cause a lock up in the high yield market?”

The second is, “could a lock up in the high yield market cause ETF investors to unduly suffer?”

The unstated comparison here is with mutual funds. We believe, however, that compared to mutual fund alternatives, ETFs actually help alleviate these concerns, not cause them.

Mutual Funds versus ETFs

Before we dive in to the specific concerns, we want to go over a very high level review of the difference between mutual funds and ETFs.

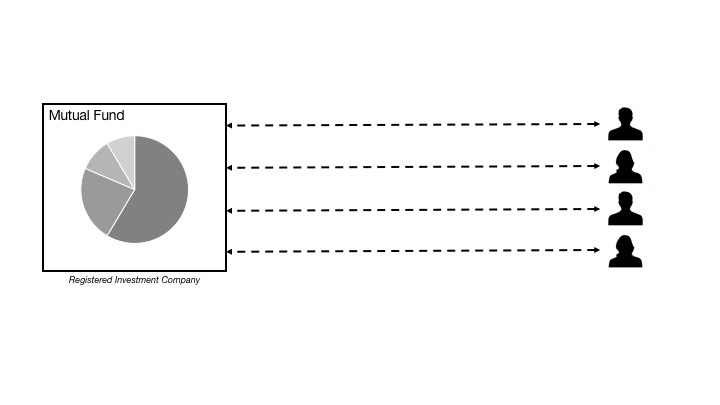

Below we have illustrated a (highly simplified) conceptual process for mutual funds.

Investors give their money to the mutual fund in exchange for shares which are priced at the net asset value (“NAV”) of the underlying portfolio. With this money, the portfolio manager buys the underlying assets. When the investor wants their money back, they redeem the share. The portfolio manager sells the underlying assets to create cash. Simple.

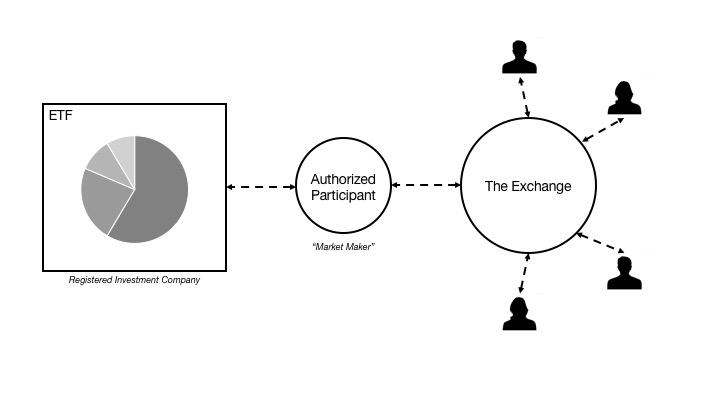

The picture for ETFs is a bit more complicated.

In this picture we introduce two new parties: the authorized participant (“AP”) and the exchange. Instead of dealing directly with the fund, investors come to the exchange to buy and sell. When those purchases or sales justify the creation or redemption of shares, the authorized participant steps in to facilitate the trade with the ETF.

The value of a share of the ETF is worth, then, whatever someone is willing to buy it on the exchange for. This price often stays close to NAV, as when it drifts too far away it creates an arbitrage opportunity.

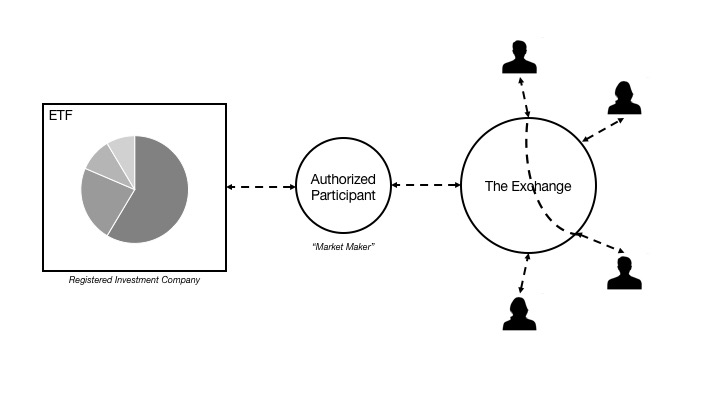

In most cases, trading looks like this:

Two participants meet at the exchange: one buying and one selling. They find an agreeable price, swap cash for shares, and the ETF manager is none the wiser. This is called “secondary liquidity.”

Two participants meet at the exchange: one buying and one selling. They find an agreeable price, swap cash for shares, and the ETF manager is none the wiser. This is called “secondary liquidity.”

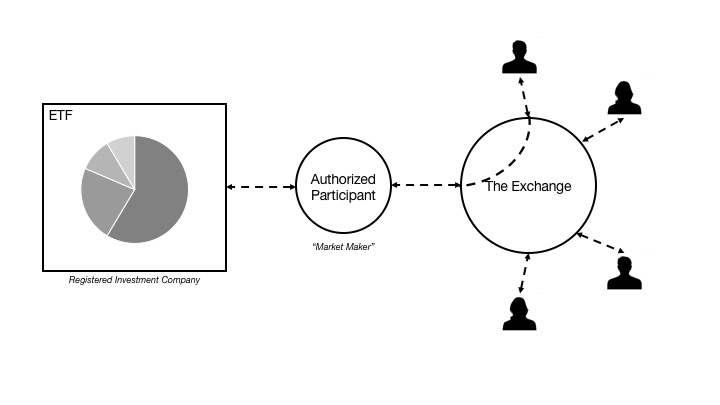

Sometimes the picture looks like this:

In this case, the AP has stepped in to help facilitate a trade on the exchange. This may happen in a less liquid ETF, where the authorized participant is the lead market maker, or in the case of a large trade. This is called “primary liquidity.”

In this case, the AP has stepped in to help facilitate a trade on the exchange. This may happen in a less liquid ETF, where the authorized participant is the lead market maker, or in the case of a large trade. This is called “primary liquidity.”

For example, let’s consider the case of an investor trying to buy a large amount of shares. The AP, knowing what the ETF is holding, creates a replicating basket of securities. The AP will then give that basket to the ETF, which will provide the appropriate number of shares. The AP will then rush back to the exchange and sell those shares to the buyer. This is the process of “creation.”

This second case happens much less frequently than the first. How much less?

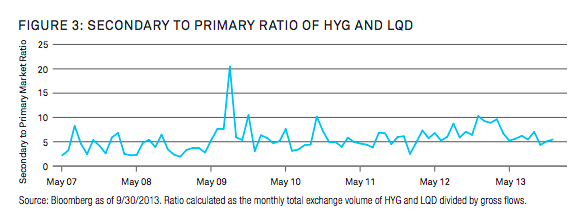

In the case of credit fixed income ETFs, like LQD and HYG, the average is close to 6:1 according to BlackRock, but can spike as high as 20:1 (August 2009). In other words, investors typically trade with each other 6 times as much as they do with the actual ETF (through the AP). During times of market crisis, investors have traded with each other even more.

Source: https://www.ishares.com/us/literature/brochure/fixed-income-etfs-and-corporate-bond-liquidity-challenge-en-us.pdf

Source: https://www.ishares.com/us/literature/brochure/fixed-income-etfs-and-corporate-bond-liquidity-challenge-en-us.pdf

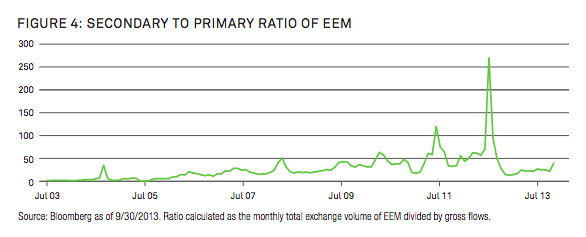

To provide another example, we can look at the emerging market EEM, where we have seen ratios exceed 25:1 for extended periods of time and spike as high as 250:1 (August 2012).

Source: https://www.ishares.com/us/literature/brochure/fixed-income-etfs-and-corporate-bond-liquidity-challenge-en-us.pdf

Source: https://www.ishares.com/us/literature/brochure/fixed-income-etfs-and-corporate-bond-liquidity-challenge-en-us.pdf

What we can see is that the exchange brings with it a secondary layer of liquidity for ETF investors to tap in to. In fact, if an ETF and a mutual fund are identically managed, the ETF should always be more liquid due to the secondary liquidity.

Can ETFs Cause Illiquid Markets?

So given this picture, could a panic among ETF investors cause a lock-up in the high yield market?

Absolutely.

No more so, however, than a panic among mutual fund investors.

The ETF is not actually the concern in this case. The concern is the significant adoption of high yield bonds among retail investors over the prior five-to-ten years due to the pursuit of yield in a low interest rate environment.

ETFs may actually provide a solution.

In a panic, mutual fund investors will simultaneously redeem, forcing fund managers to liquidate their holdings. If every fund manager is trying to sell the underlying holdings at the same time, it could cause a lockup.

ETF investors, on the other hand, will try to sell on the exchange. During a “normal” environment, the ETF manager would only have to redeem 1/7th of the volume the mutual fund would have to. Other ETF investors take care of the rest.

Let’s assume it is not normal though. Let’s assume every single ETF investor panics simultaneously and floods the exchange with sell orders. While the AP would try to facilitate orderly redemptions, what is more likely to happen is that sellers will begin to lower their asking prices, until a clearing price point is found where buyers are willing to step in.

In situations like these, the price of the ETF can trade at a meaningful discount to stated portfolio NAV. Many see this as a problem. We see it as a beneficial feature.

First, the freedom for the ETF shares to deviate from stated NAV allows market participants to make a choice about how badly they want to liquidate. Is $0.90 on the dollar worth it? There is no such decision to be made with mutual funds.

Furthermore, critics assume that the investor would have been actually able to redeem at NAV. In the case of a mass mutual fund panic where investors try to simultaneously redeem, the underlying market can lock up and investors may not actually be able to achieve NAV.

One argument we’ve heard in the past is that active mutual funds can actually facilitate a more orderly exit in illiquid markets because active managers can pick and choose which bonds to sell first, whereas most ETFs are index-based.

Our response is four fold:

- Creations and redemptions in index-tracking ETFs do not involve trading the entire basket in the first place. First, most bond ETFs employ sampling rather than full replication. Second, portfolio managers typically have the ability to use discretion in their process, weighting the benefits of liquidity vs. tracking error subject to certain limits. Third, the creation and redemption baskets typically include fewer holdings than the ETF itself.

- That “theory” didn’t work out so well for Third Avenue.

- Selling the most liquid bonds first only puts an active manager in a better position if the panic stops. If the panic continues, their portfolio gets more and more illiquid over time.

- Active ETFs do exist in both the high yield and bank loan space, so this argument is not unique to mutual funds.

Can ETF Investors Unduly Suffer in Illiquid Markets?

The second critique of ETFs is that investors can unduly suffer during periods when liquidity in the underlying portfolio dries up, as the price of the share on the exchange can deviate significantly from NAV.

Critics argue that mutual funds are much safer because investors are guaranteed NAV.

While technically true, we believe the argument misses the fact that in such an environment, NAV may no longer be a reliable figure.

The calculation of NAV requires the calculation of value for each of the underlying assets in the portfolio. If those assets haven’t traded in days, or even week, then that NAV may not actually reflect the true price an investor could achieve when they try to sell their assets.

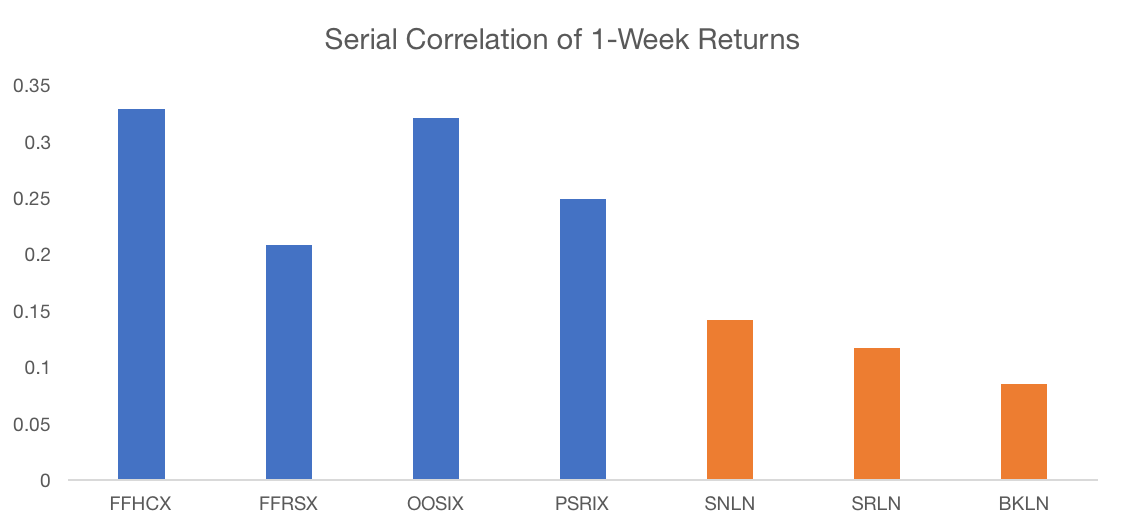

One way in which this can be seen is in the return patterns of mutual funds and ETFs on an illiquid asset class like senior loans.

Below we plot the serial correlation for weekly returns in several senior loan mutual funds as well as senior loan ETFs.

Source: Yahoo! Finance. Calculations by Newfound Research. Calculations begin at the shared inception date of all the funds.

Source: Yahoo! Finance. Calculations by Newfound Research. Calculations begin at the shared inception date of all the funds.

Serial correlation measures the relationship between one week of returns and the next. The stronger serial correlation is, the higher the chance that strong returns are followed by strong returns and weak returns are followed by weak returns.

So if these portfolios hold similar assets, why do the mutual funds have higher serial correlation?

We believe the answer is that the illiquidity of the underlying bank loans makes the NAV of the mutual funds stale. The NAV is often playing “catch-up” over multi-week periods.

Consider an example where 20% of the underlying portfolio does not trade for several weeks. Over that period, credit spreads contract and the rest of the portfolio appreciates in value. Finally, the final 20% trades and the loans jump in value, causing a jump in NAV. While this will appear as a delayed, instantaneous jump, the reality is that the value of these assets were going up over time, they just never traded and so their price did not reflect this appreciation. The NAV was using the old price in its calculation rather than the current value.

This means that in a declining market, early sellers may benefit at the cost of holders, as active managers may sell more liquid holdings first. Without a trade in the less active holdings, NAV may look steady, but could later instantaneously plummet as a trade in the illiquid underlying assets causes a recalculation of NAV.

The ability for price to deviate away from NAV with an ETF means that market participants can try to price the underlying portfolio assets without them actually having to trade. In the same situation, while 20% of the portfolio may be illiquid, ETF participants can try to guess what the loans are worth and incorporate that guess into their purchase or sale prices. With the information being incorporated more frequently over time, autocorrelation is lower.

Again, a deviation from NAV is not necessarily a problem. In this case, we believe it is a critical feature that protects ETF investors from sudden repricing shocks.

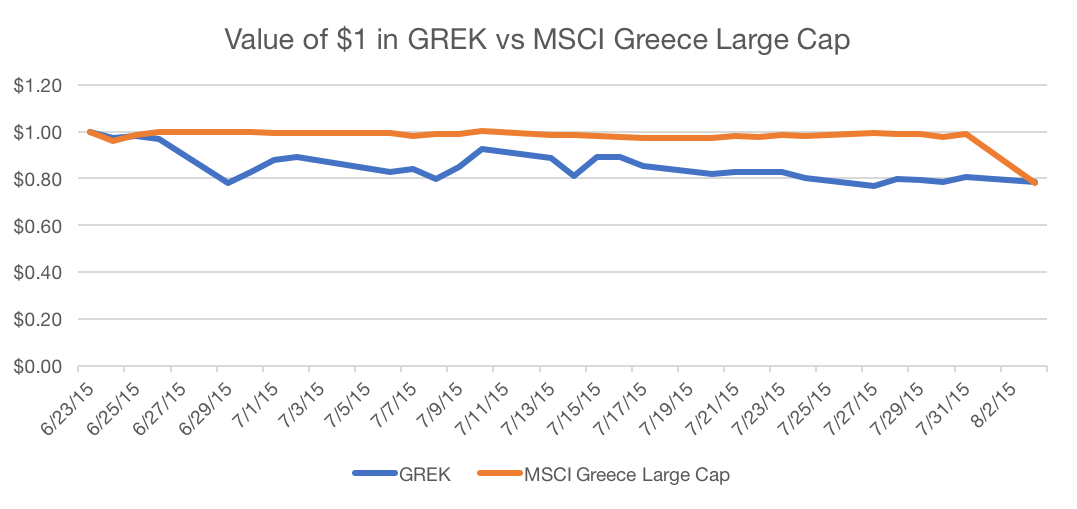

Perhaps the best example of how ETFs can add value in an illiquid market place is with an example of a completely illiquid market: Greece.

On August 3, 2015, the Greek stock market re-opened after a 5-week shutdown, plummeting 23% in a single day.

What few people know is that there is actually a U.S. listed ETF that tracks the Greek market: Global X’s GREK ETF.

During the period that the Greek market was closed, GREK was open for business. For five weeks the ETF continued to trade, with absolutely zero primary liquidity. Yet investors continued to utilize the ETF as the vehicle of price discovery.

Source: MSCI; Yahoo! Finance. Calculations by Newfound Research. Start and end dates reflect the dates for which the Greek stock market shutdown and re-opened in 2015.

Source: MSCI; Yahoo! Finance. Calculations by Newfound Research. Start and end dates reflect the dates for which the Greek stock market shutdown and re-opened in 2015.

We can see that when the market finally re-opened, it re-opened almost exactly where the ETF predicted it would.

Mind you, mutual fund investors had been locked up for 5 weeks, with zero liquidity to be had.

So while over this period the GREK ETF technically traded at a massive discount to NAV (exceeding -20%), that NAV was meaningless because it was stale and did not reflect the true value of the assets.

Conclusion

There have been countless articles written over the last several years about how the adoption of high yield and senior loan ETFs may be dangerous for both the asset classes as well as the investors.

We believe that the discussion is warranted: an abnormally large adoption of illiquid assets, all in the pursuit of yield, should cause pause for concern. At the very least, investors should be made well aware of the extra risks they are taking on.

Nevertheless, we believe the focus on ETFs specifically in this conversation is misguided. In fact, in many ways, we believe the use of ETFs helps alleviate many of the liquidity concerns raised, especially when compared to a mutual fund alternative.

Client Talking Points

- During market crises, some assets become very difficult to trade. Markets can be shut down, as in the case of Greece, and investors can fearfully react to extreme events.

- ETFs often trade much more frequently than the assets that they hold. Mutual funds that hold the same underlying assets do not have this feature.

- While investing in ETFs that hold illiquid assets comes with additional risks compared to investing in something more “standard” like the S&P 500 ETF (SPY), utilizing the ETF structure may be a good way to mitigate the risk of not being able to trade at a fair price during market crises.