by Hubert Marleau, Market Economist, Palos Management

Coming into the new year, I envisaged a reflation scenario buttressing value stocks driven by a synchronized uptick in global growth. It did not turn out the way that I figured it last October. The strength of the U.S. business cycle continued while indicators of global growth have been disappointing. In this connection, the foreign exchange market has priced in the likelihood of a diverging monetary stance between the US and the rest of world. This combined with a furious dash for safe havens, stemming from the spread of the coronavirus, gave birth to an unexpected rise in the U.S.exchange. rate The Dollar index surged and acted as a risk-off driver for value stocks. At the close on Friday, the the DXY traded at 99.09, up 2.9% since mid-January and near what technicians call a resistance level. Using simple but crude arithmetic based on imports accounting for 15% of N-GDP, one may conclude that the magnitude of the sudden increase could negatively affect consumer prices by as much as 0.4% in February alone. Import prices were unchanged on January 20, and that was before the recent surge in the value of the dollar. The CPI rose 0.1% in January, a touch weaker than the consensus and showing that inflation remains muted.

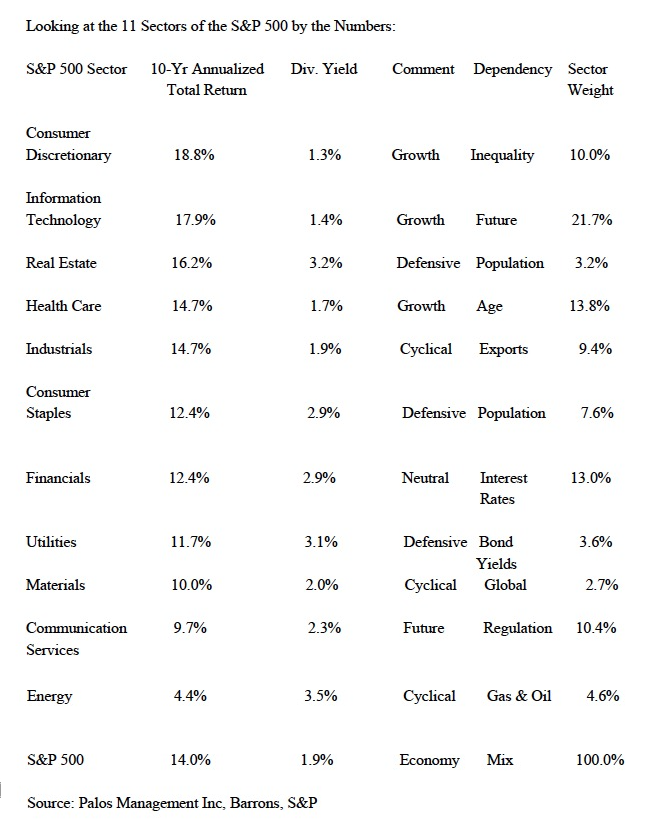

The massive inflow of foreign money into the U.S. capital and money markets has turned the dollar/inflation narrative of last year into a dollar/deflation story today. The U.S. markets agree with the thinking of the Deutsche Bank. “In the absence of a marked upturn in global growth and of stubborn prices at home, the Fed’s monetary officials may end up with no other choice than to ease the monetary stance to avert importing deflation via the currency channel.” Consequently, we have a weird economic reality. The inflow of money is pushing the level of economic activity and the price of the dollar up without the creation of inflation. In other words, the deflation imported by the strength of the dollar combined with the stubbornly low growth in wage rates is not allowing growth to generate inflation. Contrary to popular belief, trade fictions and the fallout from the coronavirus have again negated what the market once believed was inevitable—a reflation scenario. Thus, the decrease in long bond yields is driving investors to growth stocks (because the discount rate has fallen) and to defensive stocks (because the bond yields are unattractive). They have performed beyond expectations. Meanwhile, commodity prices, particularly oil prices, have fallen out of bed as a result of a reduced Asian demand. Overall, the behaviour of the markets makes good short term sense.

Thus, the question is whether the risk-on growth/defensive phenomenon will be replaced by a risk-on value rally, similar to the one which characterized the stock market performance in the latter part of last year.

A reflationary return will need a catalyst like a sustained weakness in the Greenback. I’m betting that it will. In spite of its recent strength, the U.S dollar peaked 3 years ago. Historically, the dollar has had many bearish and bullish cycles; but it’s been in a long-term downward trend since 1970. America has a fast-rising government debt level, a humongous budget deficit, a large current account deficit, a broad political divide, deep inequalities and lessen geopolitical clout. The sum of the current account and fiscal deficits has deteriorated considerably since 2017 and the prospects for a larger twin deficit are ugly. There is ample empirical evidence and theoretical validity that support the idea that the larger the twin deficits the larger the chance that the dollar will fall.

Additionally, there is more that the aforementioned long term factors that could weigh on the dollar. At first glance, the front-end inversion of the yield curve seems to be suggesting that the Fed will be forced to cut rates and increase the amount of cash in the repo market even though it does not wish for either. The Fed favours a return to normalcy. This is why the NYFed said that It will shrink its repurchase-agreement operations more than the market expected as of this Friday. An official sign that the NYFed is comfortable with removing liquidity without upending the funding of markets. Viewed in another way, it means that the Fed is fine with where short rates are. The Fed is convinced that there is enough monetary stimulus stemming from China to turn the global economy around and keep the U.S. expansion on track. The U.S. monetary officials may indeed be correct in that assessment. We’re nearly back to the peak in consumer sentiment. The University of Michigan has gauged the sentiment at 100.9 in February—the highest print since March of 2008 of 101.4, a cycle high.

The negative effects of the coronavirus will eventually die out. As a matter of fact, the coronavirus was mentioned by only 7% when the U of M asked the samplers to explain their economic expectations. Is the wisdom of the crowd right? Perhaps. Numerous agencies and followers of the epidemic have reported that the spread of the virus has slowed including the effect of Thursday’s reclassification, as the number of new confirmed cases has gradually declined.

I recognize that global industries are facing a combined coronavirus-induced demand and supply shocks. However, the disruption is more likely to be a one-off short term episode than a structural downward trend. Assuming that the coronavirus can be largely controlled by the end of March, the negative impact on the Chinese economy will be mainly confined to Q1, with a sequential rebound in Q2 to Q4 driven by pent-up demand and monetary/fiscal policy support.

Lastly, the Fed will remain heavily skewed towards dovishness. The bar for more rate cuts is infinitely lower than the bar for hikes. The whole purpose of the Fed’s current policy stance is to conjure credibility that it can rekindle a reinflation scenario.

There are two other factors that merit consideration. First, the profitability of growth stocks relative to their broad market, has been declining for two quarters in a row. Second, valuation metrics are significantly favouring materials, energy and industrial stocks. The price-ratio of value stocks to growth ones is near the historic lows of 1975 and 2000. In this respect, there is reasonable hope for a renewed rotation towards cheap value stocks. Since the 1930s, we have had 9 decades and value was in the top tier 7 times. It missed out twice, in the 1930s and 2010s.

Interestingly, Bloomberg’s Weekly Fix made the observation that “since January 24, ten-year treasuries have traded in a relatively narrow range and the 30-year bond auction with the lowest coupon on record came and went without consequence.” Perhaps the U.S. bond market is adapting to the unstable environment. It may have found an equilibrium, believing that the current regimement of low rates is here to stay and therefore not necessitating further Fed rate cut. The behaviour of market traders via options, swaps and put-calls is suggesting in a complicated way that they do not wish a rate cut but expect an eventual upwardly sloping yield curve. The CME FedWatch reported that there is only a 10% chance that there will be a rate cut on the March 18 FOMC meeting. Thus, the market is expecting a return to the reflationary narratives that dominated the thinking of investors, late last year.

The aforementioned observation is important if you happen to be a stock picker. There is a growing awareness among policy makers and investors that keeping interest rates higher than elsewhere in the world bring advantages. One only has to look at what is going on in countries that have positive real interest rates (interest less inflation rates). Their economies are doing better and so are their financial markets than those that have negative real rates. Look at Mexico, even with a highly socialist agenda, it is coming out of its recession, bond prices are increasing and the value of the peso is rising. Albeit counterintuitive, it may have been a consideration as to why the monetary officials in Australia and New Zealand decided to hold their policy rates steady last week. The Bank of Sweden raised interest rates.

Copyright © Palos Management