by Carl Tannenbaum, Ankit Mital, Northern Trust

Professional and amateur astrologists in America were all agog this past Monday, during the total eclipse of the sun. It was the first eclipse to traverse the breadth of the continental United States in nearly 100 years. Given my luck, it was not surprising that the skies over Chicago were cloudy when the event took place.

The path of full blackout passed through Jackson, Wyoming at 10:17 local time that morning. Later in the week, monetary policy luminaries from around the world assembled in that location to shed light on the pressing economic challenges of the day. Among those in the spotlight during the conference was European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi, who tried desperately to align the stars behind him.

Draghi’s current dilemma illustrates the double-edged sword of unconventional monetary policy. Central bank asset purchases and forward guidance were pressed into heavy service when interest rates reached their zero lower bound. These programs have enjoyed success, but communicating and engineering an orderly retreat will not be easy.

The eurozone has been the brightest star on this year’s economic horizon. The region’s output expanded at a 2.5% pace during the second quarter and has been rising continuously for 48 consecutive months. Even countries that had been lagging in their progress are showing better outcomes: Italy is growing at its fastest rate in six years, and we covered Spain’s improving fortunes last week. Forward-looking indicators across the continent suggest even better times ahead.

The improving outlook in the eurozone is built on a series of factors. The political risk that was present at the start of 2017 has faded; populism is in retreat and existential threats to the European Union and the euro have diminished. Financial conditions in the eurozone are more supportive: banks are healthier, interest rates are down and markets are buoyant. And because its recovery took longer to take root, Europe may have more capacity for growth in the coming years than the United States.

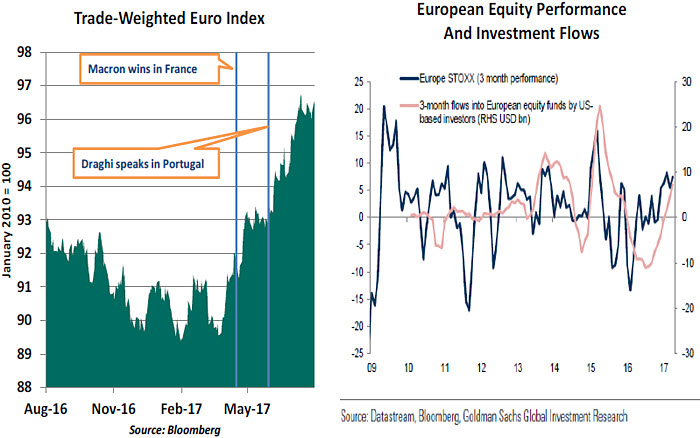

Eurozone equities have rallied powerfully on the back of these developments, attracting considerable amounts of foreign capital. To enter the region’s markets, investors have to acquire euros; this has added steam to the recent rally in the value of the common currency.

Mario Draghi furthered the euro’s momentum with his remarks at a June conference in Sintra, Portugal. "All the signs now point to a strengthening and broadening recovery in the euro area," he noted. While the full text of his speech was fairly balanced, analysts ran with the headline and assumed that Draghi was signaling intent to reduce the ECB’s asset purchase program.

Mario Draghi furthered the euro’s momentum with his remarks at a June conference in Sintra, Portugal. "All the signs now point to a strengthening and broadening recovery in the euro area," he noted. While the full text of his speech was fairly balanced, analysts ran with the headline and assumed that Draghi was signaling intent to reduce the ECB’s asset purchase program.

The strength of the euro is both a blessing and a curse for the ECB. It is a justified reflection of improving economic prospects and helps to stabilize and strengthen Europe’s asset markets. But it is also a problem: the eurozone relies on exports of goods and services for 27% of its gross domestic product (GDP), twice the level of the United States. A stronger euro makes these offerings less competitive.

Further, the eurozone imports goods and services in amounts equal to 23% of GDP. An appreciating currency makes things more affordable for consumers, but cheaper imports also make it harder for the ECB to achieve its 2% inflation target. Eurozone inflation has fallen since the early months of 2017 and now stands at just 1.3% over the past year. The minutes of the July ECB meeting noted “there was a risk that financial conditions could tighten to a degree that was not warranted by the improvement in economic conditions and the outlook for inflation.”

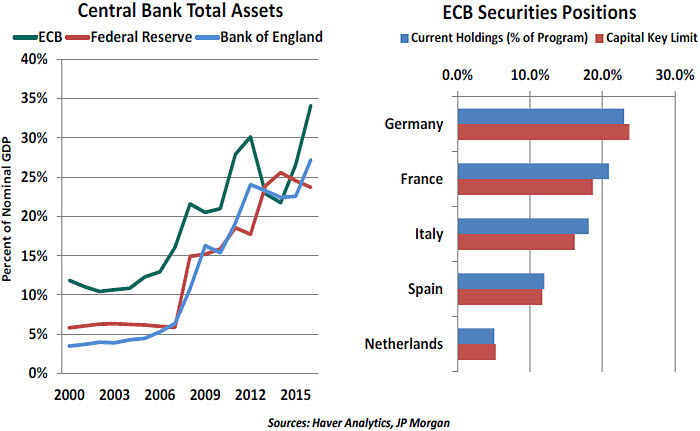

The ECB initiated quantitative easing (QE) late, and reluctantly. Differences in market structure between the eurozone and the U.S. threatened to limit the effectiveness of QE in Europe, and the stigma of the central bank monetizing burgeoning national debt made many Europeans uneasy. But once begun, the program gathered momentum quickly. And however mysterious its workings, QE has had a favorable impact on eurozone performance.

The ECB’s current round of QE is set to expire in December, so guidance on what happens thereafter should be forthcoming soon. The managing council will certainly have an active debate over how much stimulus is still needed, but future asset purchases may be limited by rule. Securities are to be purchased in proportion to the “capital key,” the ownership share of each ECB member. And holdings from any individual nation are capped at 33% of total sovereign debt. The ECB may run out of room on one or both of these fronts in the coming 12 months.

In the weeks since the Sintra speech, Draghi has expressed a degree of speaker’s remorse. He tried valiantly to adjust expectations during the press conference following the July ECB meeting, to no avail. If the situation sounds familiar, it is because Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke experienced similar frustrations during the “taper tantrum” of 2013. In that instance, the unexpected preview of reductions in central bank asset purchases caused the value of the U.S. dollar and long-term U.S. interest rates to spike. The yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note nearly doubled before settling back the following year.

In the weeks since the Sintra speech, Draghi has expressed a degree of speaker’s remorse. He tried valiantly to adjust expectations during the press conference following the July ECB meeting, to no avail. If the situation sounds familiar, it is because Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke experienced similar frustrations during the “taper tantrum” of 2013. In that instance, the unexpected preview of reductions in central bank asset purchases caused the value of the U.S. dollar and long-term U.S. interest rates to spike. The yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note nearly doubled before settling back the following year.

Having just restored some semblance of stability to the eurozone, and with Brexit negotiations presenting risks for both parties to the negotiations, the ECB is especially anxious to avoid being a source of uncertainty. It is a little easier to be predictable when using conventional tools such as interest rates. But when forward guidance is in the forefront, words become policy. Calibrating the phrasing with precision, in a manner clear to markets, is very challenging.

The next total eclipse to be visible in the United States will occur in 2024. Hopefully, the skies—and the horizon for monetary policy—will be a lot clearer by then.

Capital Flows Hit the Great Wall

We have predicted before in this space that Chinese policy makers would continue to rely on capital controls and exchange rate management to sustain financial stability. This effort has been taken to a new level, with significant effect.

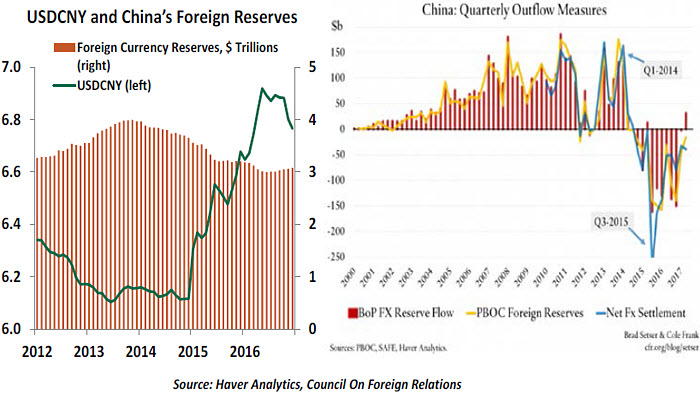

In 2014, the yuan weakened amid a steady outflow of capital from China. The next few years saw Chinese foreign reserves decline by about a trillion U.S. dollars. Reserves continued to decline until January of this year, at which point they fell below 3 trillion U.S. dollars. Since then, the decline in foreign reserves has been reversed and the yuan has stabilized against a basket of global currencies (and has appreciated significantly versus the U.S. dollar). Both Chinese financial stability and growth concerns have eased. Below, we explore the global and local implications of the measures Beijing has adopted to achieve this end.

While China has always retained controls over its capital account transactions, businesses and individuals have found ways to circumvent these controls. Over-invoicing or under-invoicing of external trade, or overpaying for investments abroad — particularly in real estate — have been undertaken for the purposes of engineering capital transfers rather than exploiting business opportunities.

The reasons for these outflows are varied: concerns over the stability of the domestic financial system amid an excess of debt; frothy asset valuation, particularly in real estate; and an official crackdown on corruption. The trend started in 2014 and accelerated in 2015 and 2016.

Chinese authorities were slow to respond, perhaps with an eye on securing the Chinese yuan’s inclusion in the International Monetary Fund’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket. Inclusion in the SDR, which bestowed the yuan with an international reserve currency status in September 2016, could have been scuttled by draconian capital controls.

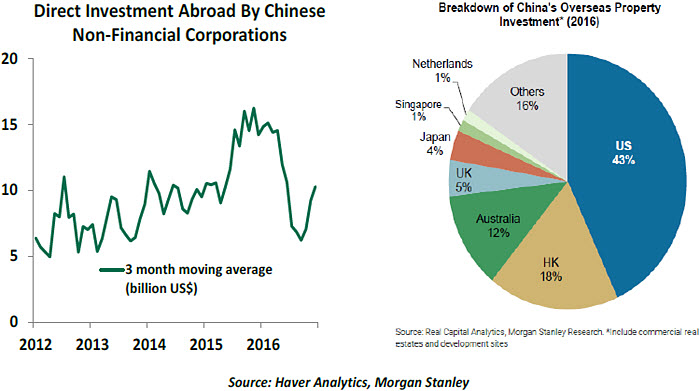

Free of those restraints, China started tightening the screws in November 2016 on what it saw as irrational investments, vanity projects or pure capital transfer schemes masked as overseas asset acquisitions. The axe fell first on international investments in property and a buyer’s non-core businesses. Overseas investments in sports, leisure and clubs were the next to attract curbs, as the Chinese central bank governor Zhou Xiaochuan singled these out as actions “not made for the best motivations.” These restrictions were strengthened earlier this month when the State Council codified regulations targeting overseas investments in property, investment and sports sector to formalize the central bank’s measures.

Mergers and acquisitions activity by Chinese businesses abroad have also attracted new limits, requiring increased scrutiny of deals by regulators, restrictions on both onshore and offshore funding for these deals and a prohibition on transactions within key industries.

Mergers and acquisitions activity by Chinese businesses abroad have also attracted new limits, requiring increased scrutiny of deals by regulators, restrictions on both onshore and offshore funding for these deals and a prohibition on transactions within key industries.

Finally, starting September 2017, overseas bank card transactions in excess of about $150 must be reported. This follows oral guidance in January 2017 asking financial institutions to maintain a balance of inflows and outflows when processing cross-border yuan payments, an order that was lifted in April 2017 after capital outflow worries had receded.

Along with a gradual and calibrated crackdown on capital outflows, the Chinese central bank has tightened its control over its exchange rate regime. Starting in May 2017, the central bank started fixing the daily yuan exchange rate using a “counter-cyclical adjustment factor” ostensibly to lean against the market-determined exchange rate. In additional, the central bank has routinely dipped into its large cache of foreign reserves to manage exchange rate levels.

As result, the yuan has stabilized this year and has appreciated significantly against the U.S. dollar. We believe China is likely to continue with a strong yuan policy for a number of reasons. Firstly, as we noted at the start of the year, sustained weaknesses in currency and capital outflows are mutually self-reinforcing. A significant reversal of yuan’s recent stability would likely prompt another round of outflows. This would hurt the recent revival in investor sentiment around China and jeopardize the success of recent capital controls.

Secondly, a strong yuan is consistent with the objective of rebalancing the Chinese economy towards domestic consumption. It serves to make imported goods more expensive, and promotes homegrown products.

All of these measures have started to have an effect. Capital flows have been positive this year, a big change from the last two years. Central bank reserves have risen every month since January 2017. While reports suggest that over-invoicing of imports and under-invoicing of exports (particularly for services) continues to mask capital outflows, we have

All of these measures have started to have an effect. Capital flows have been positive this year, a big change from the last two years. Central bank reserves have risen every month since January 2017. While reports suggest that over-invoicing of imports and under-invoicing of exports (particularly for services) continues to mask capital outflows, we have

accepted there will always be some leakages, and these do not detract from the overall

success of the policy program.

China’s efforts have constrained external flows, but trapping some capital domestically will require tighter domestic financial conditions to deal with excess liquidity.

The retreat of Chinese investors from foreign assets could cause realignment in the markets for those assets. The real estate sectors in Australia, Hong Kong, United Kingdom and the United States had been at the receiving end of the Chinese capital flows in 2015-2016, and the recent shifts have had an effect on those markets. Both transaction volumes and prices in these sectors have been impacted.

Despite long-run aspirations to become a more open economy, Chinese policy makers have revealed their clear preference for a combination of capital and currency controls. This posture should engender confidence that stability can be sustained, but may also attract concern from China’s trading partners. These issues will be the subject of debate and discussion in the months ahead.

northerntrust.com

Information is not intended to be and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation with respect to any transaction and should not be treated as legal advice, investment advice or tax advice. Under no circumstances should you rely upon this information as a substitute for obtaining specific legal or tax advice from your own professional legal or tax advisors. Information is subject to change based on market or other conditions and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

© 2017 Northern Trust Corporation. Head Office: 50 South La Salle Street, Chicago, Illinois 60603 U.S.A. Incorporated with limited liability in the U.S. Products and services provided by subsidiaries of Northern Trust Corporation may vary in different markets and are offered in accordance with local regulation. For legal and regulatory information about individual market offices, visit northerntrust.com/disclosures.

Copyright © Northern Trust