CRACKING OIL

by John Canally, Chief Economic Strategist for LPL Financial

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Overall U.S. oil consumption is still below its 2007 peak.

- Changes in U.S. oil demand have occurred partially due to government regulations that either have changed or are likely to in the near future.

- The Keystone XL Pipeline proves an important example for many of these changes.

AN UPDATE ON OIL ISSUES AND POLICIES

Patterns of energy production and consumption are changing, both because of and despite political actions; this week we look at some of the potential longer-term, structural changes to the energy market. Energy, and particularly oil, is the one commodity that we consume almost continuously. Energy also has great geopolitical implications; for many countries, securing access to energy sources or markets for energy exports is a dominant foreign policy consideration. In the last U.S. election, the use of coal and the building of the Keystone XL Pipeline were front and center policy issues, and represented real differences between the candidates with respect to energy policies. This commentary will update some of the recent trends in consumption in the oil market, including potential policy implications of President Trump’s election.

Energy – not a sea, but connected lakes

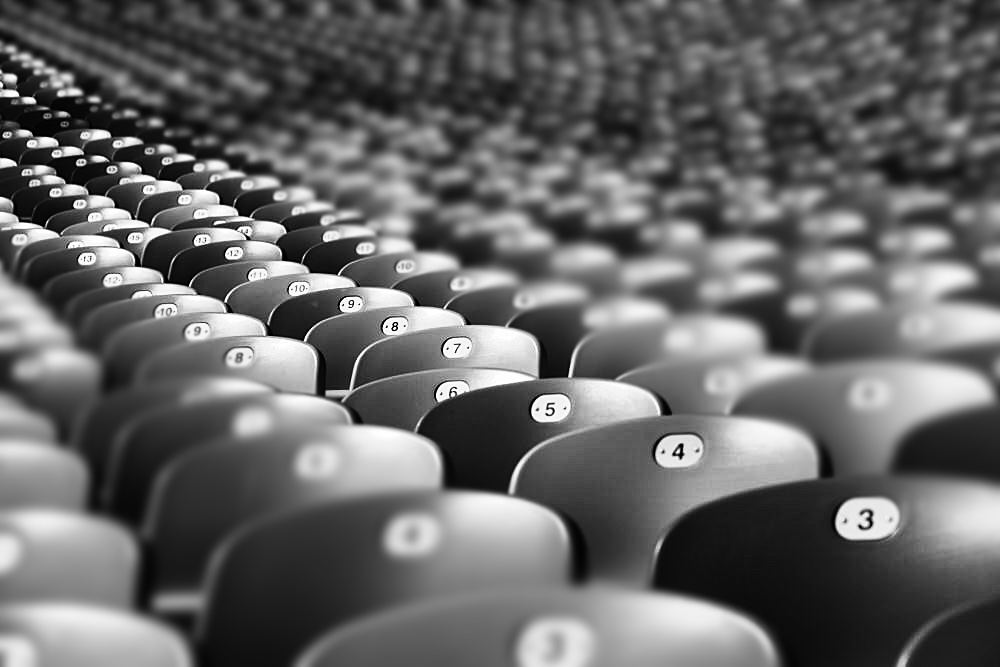

Despite an increasing population, overall U.S. energy consumption has remained relatively constant over the past few years [Figure 1]. Overall, U.S. energy consumption peaked in 2007; however, the type of energy we consume has changed and is likely to continue to do so. Therefore, when we think about energy and energy policy, we must really think about what form it is in, where it comes from (domestically produced or imported), and of growing importance, where we might be exporting it to. It is not a coincidence that a string of important political figures, including former Vice President Dick Cheney and current Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, were CEOs of oil and gas companies.

Energy may continue to be a major source of international conflict. Wars, both proxy and direct, have been fought over the ability to secure its supply. Securing access to energy has been a major driver of many nations’ foreign policies, including the U.S., France, and Germany. More recently, China has been securing access to oil in Africa. Though the issue regarding Chinese activity in the South China Sea is complicated and beyond the scope of this commentary, access to the Sea’s estimated 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas is at least a partial consideration in China’s actions. Ensuring the ability to export energy and strategic use of these exports has been a major policy concern for the U.S.S.R./Russia and many Middle Eastern countries.

During the campaign, Trump and his advisors generally preferred to focus on energy security by encouraging additional domestic sources of energy production. Candidate Trump promised to expand drilling offshore and in national parks, reversing the Obama administration’s policies. However, he has yet to enact such policies. More importantly, given the current supply/demand situation globally, including a relatively narrow range for the past 10 weeks (and only then because of OPEC production cuts), it is not clear how many projects would be economically viable with oil near current prices.

We love our cars

Oil is typically the first source of energy we think about when the topic is introduced. Unlike other sources of energy, historically the U.S. has imported a great deal of oil. Our relationship with oil is changing however, with increased domestic production from shale deposits in Texas and Oklahoma, as well as the Bakken oil basin in Montana and North Dakota. This production increase has been well documented elsewhere. It would likely take a significant increase in oil consumption to change where we source oil from. Oil demand does vary to some degree. Currently, approximately 70% of oil consumed in the U.S. is used for transportation, which means the primary “drivers”—pun intended—of oil consumption are consumer choices on miles driven and the fuel efficiency of vehicles.

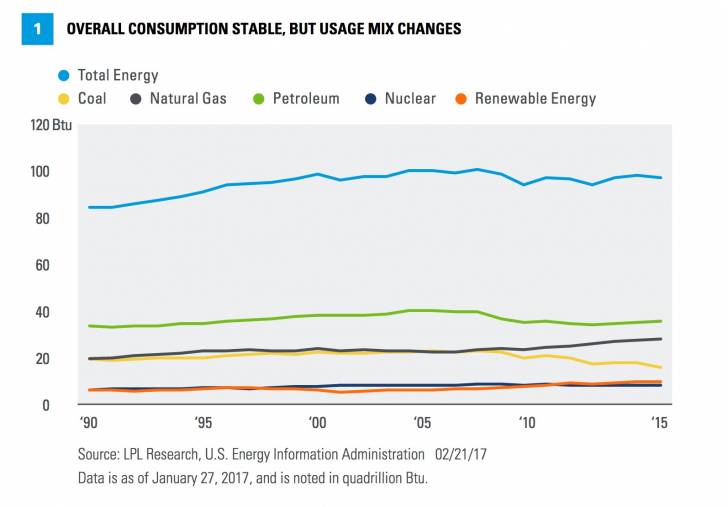

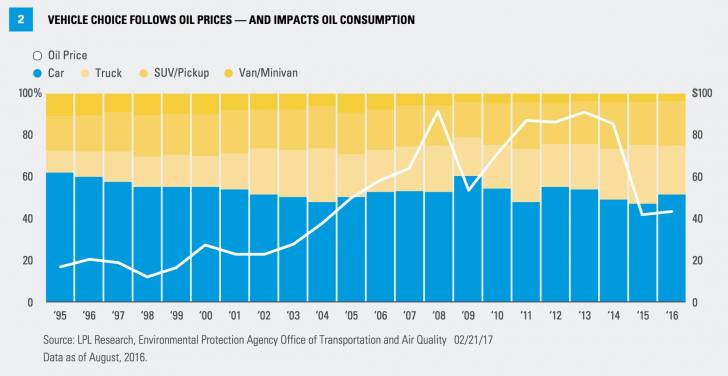

Historically, the vast majority of passenger vehicles were cars, and the oil crises of the 1970s encouraged Americans to buy more fuel-efficient cars though the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards passed by Congress in 1975. The advent of new types of vehicles had drivers abandoning traditional car models for less fuel-efficient models such as SUVs, pickup trucks (often retooled for white collar workers), and minivans. By 2001, traditional cars were no longer the majority of passenger vehicles purchased [Figure 2]. Years of low oil prices also encouraged this shift in consumer preferences. That trend was reversed in 2005, as oil prices started to climb after their 2002 lows and investors purchased more cars. It wasn’t until 2014, when oil prices began to decline, that traditional cars once again represented less than 50% of vehicles purchased.

The Obama administration put forth rules that would increase fuel efficiency standards to 52.4 miles per gallon by 2025, though in practice there are multiple loopholes that would result in a lower figure. All vehicle classes have become more fuel efficient as a result of CAFE standards and changing consumer preferences [Figure 3]. Even so, if the Obama rules stand, auto manufacturers would be under pressure to comply. Recently, 18 car manufacturers sent a letter to the Trump administration asking it to review and revise these new standards. Though President Trump criticized a number of specific environmental rules while campaigning, we can find no record of Trump criticizing CAFE standards directly. However, Trump did promise to sign executive orders on a variety of regulatory issues sometime this week at the swearing in of Scott Pruitt, the newly confirmed head of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). It’s possible that at least a reconsideration of the stricter CAFE standards is part of that package.

Keystone XL update

The highly controversial Keystone XL pipeline was often mentioned during the presidential campaign. We noted that the battle over Keystone became more of a political litmus test than a true discussion over the merits of the project. In brief review, the Keystone XL pipeline is a proposal to build a new link between the oil sands in Alberta, Canada to the main U.S. pipeline system in southern Nebraska. As a candidate, Donald Trump promised to restart the Keystone XL project, which had been effectively sidelined by the Obama administration. On January 24, Trump signed executive orders inviting the project’s Canadian partner to resubmit the proposal to the State Department, and for the Department to respond within 60 days. Given that the current Secretary of State is a former oil company CEO, it seems safe to assume the project may be approved.

Those are the politics, but what are the economics? Three things have changed since Keystone XL was proposed in 2008. First, while oil prices were over $100/barrel at that time, oil has more recently been in a tight trading range of between $50 and $55/barrel. Second, the costs associated with extracting this Canadian oil have come down as well, from somewhere between $80 and $100/barrel in 2008 to $50 and $90/barrel today,[1] with the variation determined largely by whether the project is an extension of an existing project or a brand new effort. With sustained prices over $65/barrel unlikely (barring a major geopolitical upheaval), profitable production from the oil sands is expected to be limited. The third change is that as of December 2015, it is now legal to export oil from the United States, with increasing shipments headed to Asia. The ability to export oil will encourage both U.S. and Canadian oil production (delivered through Keystone XL), provided prices stay high enough.

CONCLUSION

Changes in the energy markets will continue, particularly in how oil is produced, consumed, and even exported. The Trump administration has promised significant change to U.S. energy policy; we do not doubt this intention. In other words, we may take President Trump both seriously and literally on energy policy. We continue to believe that, barring major geopolitical disruption, the upside for oil is contained, with prices unlikely to move above $60–$65 for a sustained period of time. There is simply too much untapped supply in the U.S. The Trump administration’s pro-drilling policies will serve to limit oil price increases as it gets easier for companies to bring more supply to market. However, government policy is only one factor in the energy markets. Economics, geology, and global politics will also play a part in the energy outlook.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results.

Any economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

Investing in stock includes numerous specific risks including: the fluctuation of dividend, loss of principal and potential illiquidity of the investment in a falling market.

Because of its narrow focus, specialty sector investing, such as healthcare, financials, or energy, will be subject to greater volatility than investing more broadly across many sectors and companies.

The fast price swings in commodities and currencies will result in significant volatility in an investor’s holdings.

All investing involves risk including loss of principal.

[1] IHS Markit.