by Scott Brown Ph.D., Chief Economist, Raymond James

Fed Chair Janet Yellen will present her monetary policy testimony to Congress on Tuesday and Wednesday. We may not learn much new regarding the pace of future rate increases (which will remain data-dependent) and she’s certain to avoid getting into any discussion of fiscal policy. However, the Fed is now the chief supervisor of the financial system and, even if she is viewed as a lame duck (her term as Fed chair ends February 3, 2018), she ought to have a lot to say about financial regulation.

After some second-guessing in recent weeks, stock market participants remain generally enthusiastic. The Trump trade is back in gear. However, most economists are less enthusiastic. Expectations of near-term economic growth have been raised, but there are constraints ahead in the labor market, fiscal policy changes have to come through a contentious and difficult process, and there is a danger of a major mistake on global trade. It’s uncertain how these two conflicting views will be resolved. Yellen may not provide much clarity, but it will interesting to hear the Fed’s views on the outlook, as well as the risks and uncertainties. Remember, she’s there to present the view of all Fed policymakers, not just to give her own opinions.

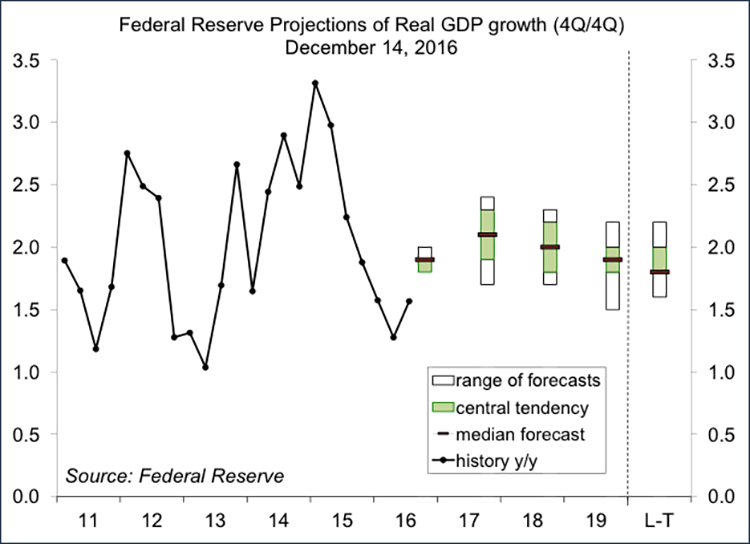

Fed officials did not formally update their economic projections at the recent policy meeting, so Yellen may simply rehash the mid-December outlook. At that meeting, some officials, but not all, incorporated fiscal stimulus into their forecasts. Most Fed officials see the economy as being near full employment. Hence, fiscal stimulus may not add much to the growth outlook. Still, Yellen should take note that the size, composition, and timing of fiscal stimulus is uncertain. The Fed is not going to base monetary policy decisions on what Congress might do. There’s a strong belief that the central bank has the ability to wait to see what Congress does. There’s little danger of the Fed falling behind the curve.

The Fed’s economic outlook is likely to be a mixed bag. Job growth is expected to remain relatively strong in the near term, but will slow as labor market constraints become more binding. Wage growth, while uneven from month to month, is trending gradually higher. Yet, while nominal wage growth is gently moving up, inflation-adjusted wage growth has slowed significantly (reflecting the firming in gasoline prices). Hence, consumer spending growth ought to remain moderate – not weak, but not especially strong either. In contrast, beginning last summer, business fixed investment appeared to be emerging from a slow patch. The global economy, while not booming, is looking better. Thus, capital spending should add to overall economic growth in the near term. However, the consumer sector is a much larger part of the economy, so the upside prospects for growth are likely to be more limited than stock market participants seem to be anticipating.

The Fed has two goals, maximum sustainable employment and stable prices (in practice, this is taken to be low inflation – 2% per year in the PCE Price Index). Over the long term, these are often viewed as one goal. That is, keeping inflation low will lead to better job growth over time. Inflation is a monetary phenomenon, but its approach is visible through pressure in resource markets. The labor market is the widest channel for inflation pressure. Most Fed officials fear that wage inflation will be passed along in higher price inflation. However, that depends on the ability of firms to raise prices. Higher wage inflation could lead to a more efficient allocation of labor, boosting productivity growth. The Greenspan Fed took a risk in the late 1990s, allowing the unemployment rate to fall below a level many thought to be consistent with full employment. That period coincided with rapid technology change and a misallocation of capital (the dot-com bubble). It’s hard to separate the effects (Fed policy vs. technology), but we saw major changes in the job market (a high level of job destruction and a high level of job creation, but net gains). It’s unlikely that the Fed will repeat that experiment.

The financial crisis was due in part to the absence of a systemic regulator (no one overseeing the financial system as a whole). The Federal Reserve has that role now. Since the election, financial stocks have rallied on the expectation of a rollback of regulations. However, there’s little evidence that regulation has been a major constraint on bank lending. On Friday, Daniel Tarullo, the key Fed governor on regulation and supervision, announced his resignation (effective April 5). President Trump will nominate his replacement (in addition to filling two currently vacant Fed governor slots and choosing Yellen’s replacement as Fed chair). This week, expect Yellen to emphasize the importance of central bank independence and the Fed’s critical role in regulating the financial system.

Copyright © Raymond James