In Times Like These

We Invest for the Long Term, But We Live in the Here and Now

by R. P. Seawright, Above the Market

“My Mama told me there’d be days like this.” – Van Morrison

Stock markets are in turmoil all over the globe. Monday was especially violent and what passes for financial television was awash in bluster, doom and gloom. Markets were gapping down in China, in London, in Japan and elsewhere. Emerging markets were getting crushed. Here in the States, the S&P 500 dropped about 4 percent, with the other major benchmarks performing similarly. The next day, on what appeared to be “Turnaround Tuesday,” a day-long rally was overcome by a major sell-off just before the close, pushing all the major indexes underwater for yet another day. Today has opened well, but (obviously) we don’t know what’s coming.

Over the previous six trading days, the benchmark S&P index has lost well over 200 points, or roughly 11 percent, putting it on track for its worst August in 17 years. But since the markets haven’t seen a significant correction (a loss of at least 10 percent) since 2011, we have been due for one. When financial markets are free-falling, and all correlations seem to converge on 1.0, analytically we move into the realm of the physics of landslides, where things are inherently complicated and unpredictable (which is not to say that more “normal” times are somehow simple and predictable).

As I have been pointing out for a long time, stock prices have been rising steadily in relation to earnings and market valuations have been quite high by nearly every measure. Back in February, Andrew Smithers, an important London-based analyst, warned that the U.S. market was trading seventy per cent above its fair value. In May, Robert Shiller, the Nobel laureate economist who teaches at Yale, said that there is a ”bubble element“ to the valuations present in the market.

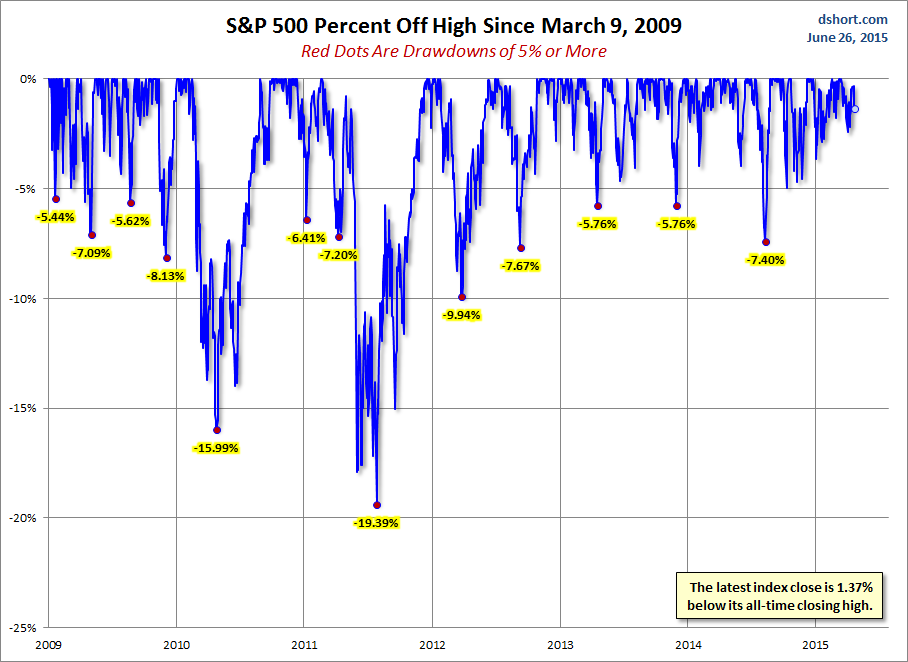

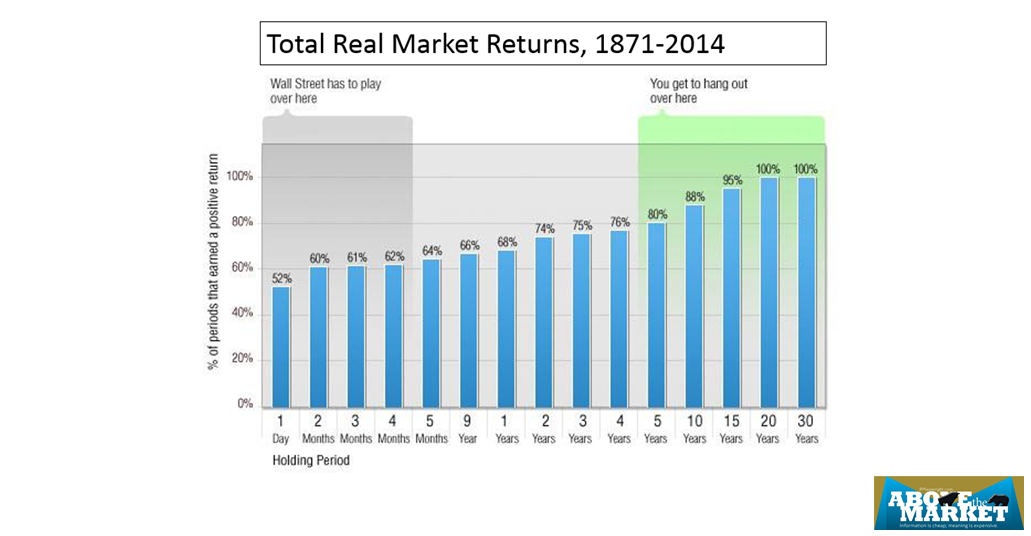

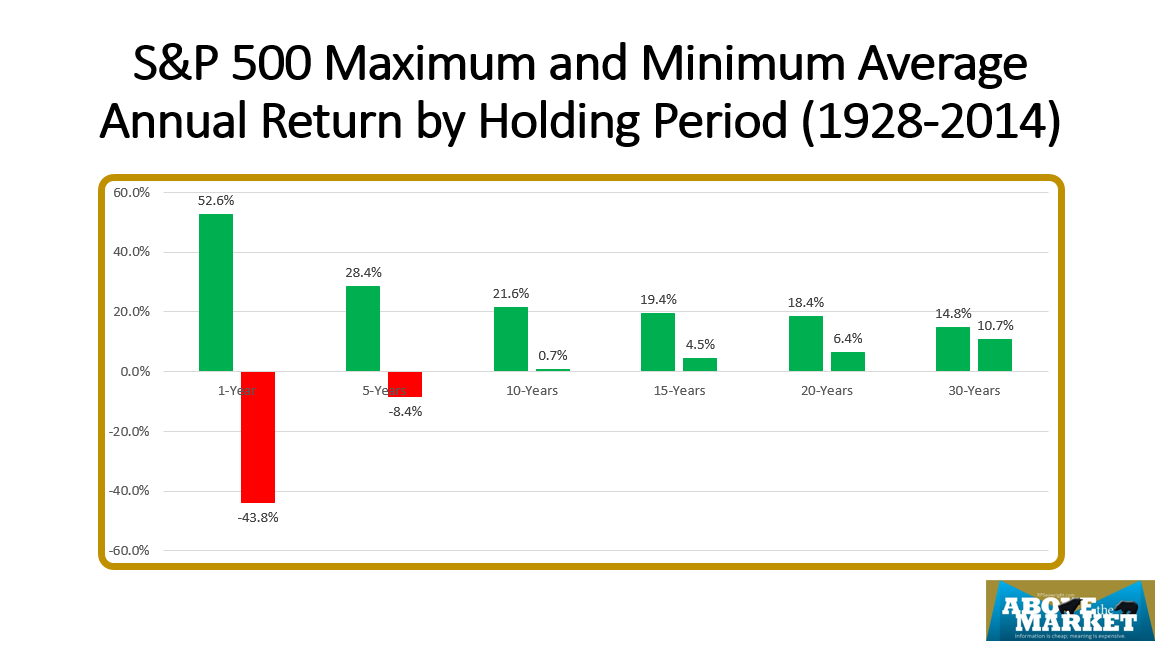

Moreover, serious drawdowns are simply par for the course in the markets. Investing requires that we be prepared for major losses. That risk is the price we pay for the excess returns provided by stocks relative to other investment choices. Even during a terrific bull market, serious drawdowns are part of the package. Note the extent of the drawdowns during the post-financial crisis period when the S&P 500 gained more than 200 percent but before the current correction (see below).

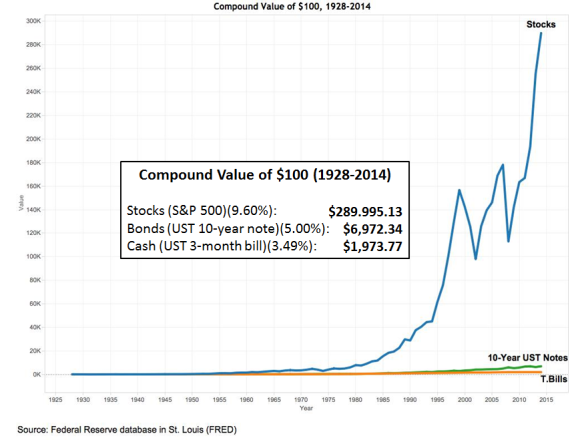

A broad index of U.S. stocks increased 2,000-fold between 1928 and 2013, but lost at least 20 percent of its value 20 times during that period. If you can’t stomach significant volatility as a price paid for much higher returns, you shouldn’t be in the market. But I bet those who are afraid to invest in stocks don’t realize how much they’re giving up by avoiding the stock market. Spoiler alert: It’s a lot (see below).

A broad index of U.S. stocks increased 2,000-fold between 1928 and 2013, but lost at least 20 percent of its value 20 times during that period. If you can’t stomach significant volatility as a price paid for much higher returns, you shouldn’t be in the market. But I bet those who are afraid to invest in stocks don’t realize how much they’re giving up by avoiding the stock market. Spoiler alert: It’s a lot (see below).

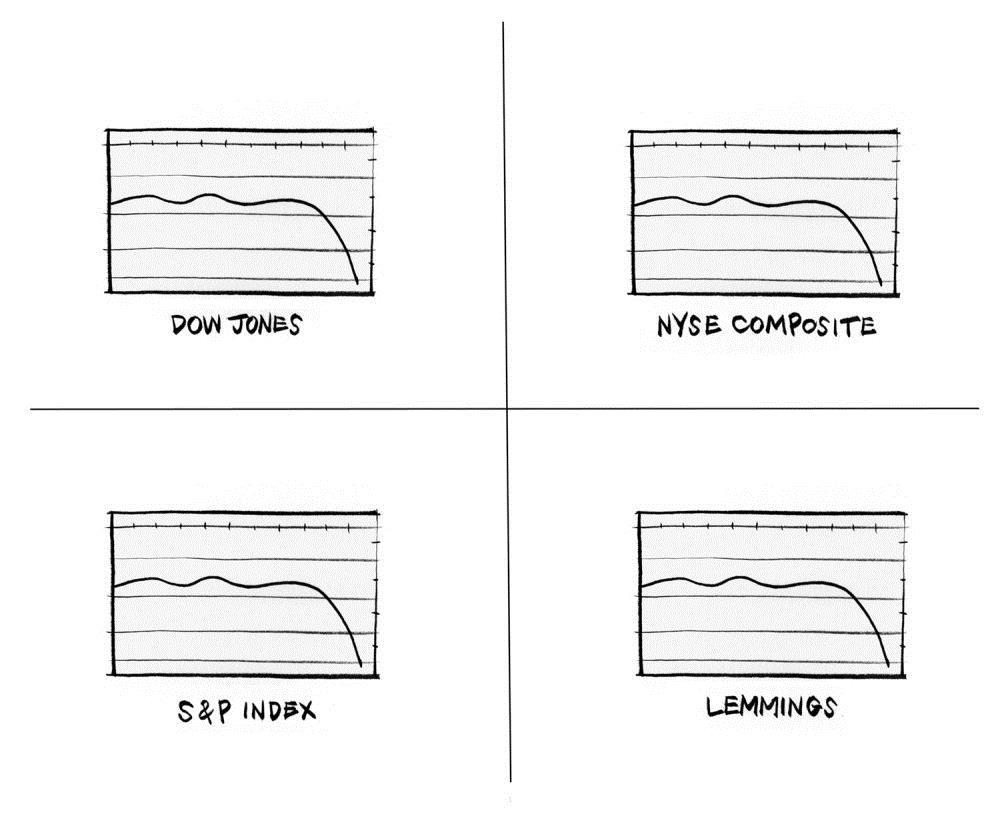

Our first reaction on ugly days in the markets is pain. Because of our loss aversion, we feel investment loss at least twice as strongly as we feel a similar gain. Thus we are seemingly hard-wired to overreact to losses. Accordingly, our second reaction on ugly days in the market is often to sell.

Source: The New Yorker

Source: The New Yorker

But selling is usually a really bad idea.

The above charts demonstrate that if we have the wherewithal to keep our composure during difficult markets, we will be rewarded for it. According to University of Oregon economist Tim Duy, “As long as people have babies, capital depreciates, technology evolves, and tastes and preferences change, there is a powerful underlying impetus for growth that is almost certain to reveal itself in any reasonably well-managed economy.” Numerous studies have shown that those who trade the most earn the lowest returns. Remember Pascal’s wisdom: “All man’s miseries derive from not being able to sit in a quiet room alone.” Overtrading is indeed a big killer of returns. As Brad Barber and Terry Odean showed in a landmark 2000 paper, “trading is hazardous to your wealth.” Yet our instinctive reaction to every market correction or downturn is to change something and almost always to sell something.

The above charts demonstrate that if we have the wherewithal to keep our composure during difficult markets, we will be rewarded for it. According to University of Oregon economist Tim Duy, “As long as people have babies, capital depreciates, technology evolves, and tastes and preferences change, there is a powerful underlying impetus for growth that is almost certain to reveal itself in any reasonably well-managed economy.” Numerous studies have shown that those who trade the most earn the lowest returns. Remember Pascal’s wisdom: “All man’s miseries derive from not being able to sit in a quiet room alone.” Overtrading is indeed a big killer of returns. As Brad Barber and Terry Odean showed in a landmark 2000 paper, “trading is hazardous to your wealth.” Yet our instinctive reaction to every market correction or downturn is to change something and almost always to sell something.

As David Rosenberg explains, “Corrections are part and parcel of the investment process, they come and go, and it is imperative to take a deep breath and realize that what is most important for building wealth is not ‘timing’ the market but rather ‘time in’ the market.” It pays to stay invested. So please listen to Wesley Gray: “You can lead an investor to a winning strategy, but you can’t make them stick with it when the going gets tough. Unfortunately, success comes at a steep price. You need to be willing to sit through periods of downright dreadful performance. No risk, no reward. It really is that simple.”

None of which is to say that we’re going to like doing nothing when it feels like the world is collapsing around us. Since the greatest possible portfolio does no good whatsoever if you don’t stay invested and since we are surprisingly prone to bailing at the first sign of trouble, let’s review our other options.

We can try to time the market

Princeton’s Burton Malkiel proclaims the stark reality. “There isn’t anybody who can tell you what’s the best asset class for 2015. Nobody. I’ve never known anybody who can time the market. I’ve never known anybody who knows anybody who can consistently time the market.”

Market forecasting — which is the essence of market timing — has a long and ignominious history (as I have written many times). Irving Fisher was a noted 20th century economist. No less an authority than Milton Friedman called him “the greatest economist the United States has ever produced.” But just three days before the famous 1929 Wall Street crash (timing is everything) he claimed that “stocks have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” Similarly, on March 6, 2009, Michael Boskin argued that “Obama’s Radicalism Is Killing the Dow.” Stocks bottomed just three days after publication (timing is everything) and the Dow has gained over 171 percent since, through the end of 2014.

Since 1990, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia has conducted a quarterly Survey of Professional Forecasters, continuing research conducted from 1968-1989 by the American Statistical Association and the National Bureau of Economic Research. The survey asks various economic experts their views of the probabilities of recession for each of the following four quarters and comes up with an “Anxious Index” reflecting those asserted probabilities.

A CXO study of that data determined that the forecasted probability of recession for a quarter explained absolutely none of the stock market’s returns for that quarter. In fact, the data suggests that the forecasts were a mildly (if not materially) contrarian indicator of future U.S. stock market behavior. In other words, you’d be better off doing the opposite of what the experts suggested than following their advice! The lousy track records highlighted by CXO are entirely consistent with a long line of research (most prominently from Philip Tetlock) establishing the lack of value provided by so-called “expert” forecasters.

It’s also easy to prove how error-prone we are in the investment world. Every year I take a look at various predictions for the year that’s ending and they are uniformly lousy in the aggregate. Moreover, when somebody does get one right or almost right, that performance quality is not repeated in subsequent years.

2014 provided more of the same in this regard. The median S&P 500 forecast among 50 top-end investment experts called for a year-end level of 1,950, up 6.44 percent on the year. The actual closing level was 2,059, up 11.39 percent, essentially five full percentage points higher. That’s a miss of monumental proportions.

In January of 2014, analysts called for far higher oil prices, firmer inflation, a worse jobless rate and higher interest rates for the coming year. The exact opposite happened in each of those areas. The consensus crude oil price forecast was nearly $95 per barrel (up a bit) and 72 out of 72 economists were anticipating higher interest rates and lower bond prices. Advisor magazine reported that bond market sentiment was utterly bearish, leading pundits to recommend that investors limit their bond holdings to the shortest maturities in 2014. Meanwhile, 30-year U.S. Treasury bonds returned nearly 30 percent. In April of 2014, Peter Schiff of EuroPacific Capital made the bold prediction that the “Federal Reserve’s quantitative-easing program will push gold to $5,000 an ounce.” The shiny yellow metal closed 2014 at just under $1,200, 80 percent or so lower than Schiff’s target. Getting even the macro picture right is extremely difficult at best.

Alleged experts miss on their forecasts and miss by a lot pretty much all the time. Let’s stipulate that these alleged experts are highly educated, vastly experienced, and examine the vagaries of the markets pretty much all day, every day. But it remains a virtual certainty that they will be wrong often and often spectacularly wrong. On account of hindsight bias, we tend to see past events as having been predictable and perhaps inevitable. Accordingly, we think we can extrapolate from them into the future. But the sad fact is that we can’t buy past results.

For what it’s worth, individual investors do even worse than the alleged professionals. The S&P 500’s total return of roughly 14 percent in 2014 was 40 percent higher than its 25-year average annual gain. It printed over 50 all-time record closes. But according to MSN Money and its annual survey of “Main Street” retail investors — as opposed to Wall Street pros — individual investors came up with an average 2014 forecast that U.S. stocks would decline “at least” 10 percent for the year, a wild miss of nearly twenty-five percentage points.

I’ve gone to a lot of trouble to show unequivocally that nobody’s remotely close to perfect in the investment world. In fact, very few people are very good. Yet we all like to think that we’re the exception to the rule. We screw up repeatedly and then insist we knew it all along. We even forget (or ignore) how poorly our investments have actually done. Still, we love to think that there is a market magic bullet and “I’m just the person to find it (because I deserve it).”

As Tim Richards explains, we are both by design and by culture inclined to be anything but humble in our approach to investing. We invest with a certainty that we’ve picked winners and sell in the certainty that we can re-invest our capital to make more money elsewhere. But we are usually wrong, often spectacularly wrong. These tendencies come from hard-wired biases and also from emotional responses to our circumstances. But they also arise out of cultural requirements to show ourselves to be confident and decisive. Even though we should, we rarely reward those who show caution in the face of uncertainty.

As the legendary investor Peter Lynch famously emphasized, “Far more money has been lost by investors preparing for corrections, or trying to anticipate corrections, than has been lost in corrections themselves.” Charles Kirk expresses it similarly: “Far too much money has been lost by those constantly preparing for and fearing the worst, than simply doing their job to focus on what is actually happening in the market, not what they fear will happen instead.” The great Peter Bernstein explains: “Even the most brilliant of mathematical geniuses will never be able to tell us what the future holds. In the end, what matters is the quality of our decisions in the face of uncertainty.” Mean reversion is powerful and often overlooked, especially in the midst of 6+ years that have been as good as many are likely to see for investing in stocks.

We love confident certainty and a tidy resolution. We so badly want to believe that we have (finally) figured out the path to investment success that we keep making the same mistakes over and over again. The bottom line here is that anyone who thinks it’s possible to predict the future in the markets ought to think again. Your crystal ball does not work any better than anyone else’s. Trying to time the market is a fool’s errand.

We Can Avoid Stocks

Another potential response to market unrest is to move away from stocks entirely. Many millennials came of age during the most terrifying financial crisis since the Great Depression, which shaped and still impacts their investing decisions today. Others got double-dipped – suffering through both the dotcom bubble at the turn of the century and the 2008 financial crisis. It’s not altogether surprising then that nearly 60 percent of millennials in a recent survey say they distrust financial markets while just 26 percent of people under 30 are invested in stocks, even though stocks went essentially straight up for more than six years until the recent blip.

But this reticence to invest is not exclusively a problem for millennials. Nearly everybody who is active and aware in the markets knows people who got hurt in the markets, bailed, and couldn’t bring themselves to get back in or who waited far too long to get back in. Fewer than 50 percent of all adults own stocks. And failing to own stocks has very serious consequences.

That’s right. It’s not a misprint. The difference is astronomical. If you kept $100 safely in 3-month U.S. Treasury bills from 1928 through 2014, you could have earned 3.49 percent, turning that $100 into $1,973.77; $100 in 10-year U.S. Treasury notes, a good, safe bond investment, would have earned you 5 percent, meaning that your $100 grew to $6,972.34. But $100 in the S&P 500 over that same period would have returned 9.6 percent, meaning that your $100 grew to $289,995.13. The difference between $7,000 and $290,000 is pretty significant, don’t you think? No wonder compound interest is often described as the eighth wonder of the world.

That’s right. It’s not a misprint. The difference is astronomical. If you kept $100 safely in 3-month U.S. Treasury bills from 1928 through 2014, you could have earned 3.49 percent, turning that $100 into $1,973.77; $100 in 10-year U.S. Treasury notes, a good, safe bond investment, would have earned you 5 percent, meaning that your $100 grew to $6,972.34. But $100 in the S&P 500 over that same period would have returned 9.6 percent, meaning that your $100 grew to $289,995.13. The difference between $7,000 and $290,000 is pretty significant, don’t you think? No wonder compound interest is often described as the eighth wonder of the world.

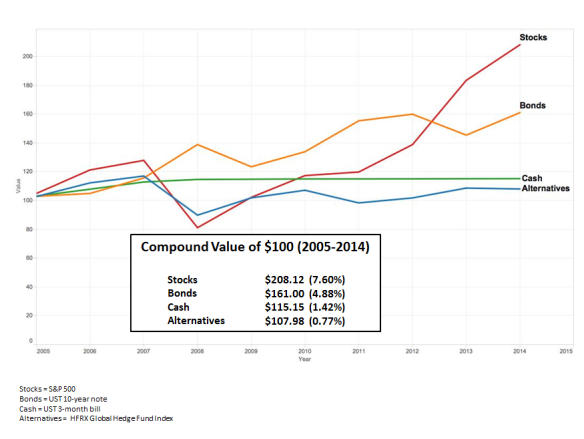

And if you think that the chart doesn’t really paint an accurate picture because things are different now somehow, let’s have a look at just the last ten years, which allows us to include so-called “alternative investments.”

Same story. Despite an historically bad stock market crash, a great environment for bonds, and huge interest in alternatives, stocks win easily. Note too that, over the same period, a representative fixed index annuity (the American Equity Bonus Gold), which is a common retail purchase to avoid losses, returned 5.18 percent, slightly more than bonds but substantially less than stocks. And even if we push up the time line such that the ten-year cycle for stocks ends with yesterday’s carnage, the 10-year annualized return for stocks is still 6.56 percent; stocks still decisively outperform the other choices.

Same story. Despite an historically bad stock market crash, a great environment for bonds, and huge interest in alternatives, stocks win easily. Note too that, over the same period, a representative fixed index annuity (the American Equity Bonus Gold), which is a common retail purchase to avoid losses, returned 5.18 percent, slightly more than bonds but substantially less than stocks. And even if we push up the time line such that the ten-year cycle for stocks ends with yesterday’s carnage, the 10-year annualized return for stocks is still 6.56 percent; stocks still decisively outperform the other choices.

As the great Jason Zweig of The Wall Street Journal explains, “the most important thing psychology tells us is that people learn almost nothing from history.” History tells us that if you want your investment portfolio to perform, you have to include a healthy dose of stocks. There’s no way around it. The Financial Times sums it up with the simple declaration: “In the long-term, nothing beats stocks.” Moreover, if you want to earn enough money to retire comfortably, you will almost certainly need a healthy dose of stocks in your portfolio.

On the other hand, if you have already won the game, there is no good reason to keep playing. In other words, pre-retirees with plenty of savings needn’t own risk assets (or at least risk assets in large proportions). However, the number of American workers who are in that category is remarkably small. The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College projects that a sizable minority of Baby Boomers and a majority of Gen Xers will experience falling living standards in retirement. And since the average 401(k) balance is less than $100,000 and since even long-time savers have an average balance of roughly $250,000 (which won’t fund retirement for many, even with Social Security), not nearly enough of us are “there” yet. Avoiding stocks is a fool’s errand too.

We can reevaluate

Obviously, locking the barn door doesn’t do any good once the horse has escaped and reevaluating one’s investment choices in the midst of big-time volatility when emotions are running hot is very dangerous business indeed. But if the past week has freaked you out utterly (some significant level of freakishness is utterly normal), you have clearly overestimated your risk tolerance. In that case you should reevaluate your portfolio, recognizing that lowering risk will almost surely mean working longer, perhaps much longer (assuming you have the opportunity), that your longer-term returns will almost surely be lower, perhaps much lower, and thus the resources to which you will have access will be substantially less than if you had invested more heavily in stocks.

Possibilities include (a) increasing allocations to bonds and/or alternatives or (b) hedging (my favorite is dynamic hedging using puts to limit portfolio downside). These approaches make very good sense for a much broader class of investors who need or will need retirement income from their portfolios during the few years before and after retirement to limit “sequence risk.”

Again, a great portfolio doesn’t do you any good if you don’t own it so some accommodations may have to be made to best practices to keep our emotions from getting the best of us. Simply repeating “stay the course” over and over doesn’t mean we’ll have the wherewithal actually to do it.

The long-term is not where life is lived. We exist only in the here and now. We conceive of the past via a hazy set of fallible memories and biochemical impulses, often tinted by the warm and rosy glow of nostalgia. However, the past can also be dark, traumatic, and painful, haunting its survivors. Those often contradictory experiences, perhaps mixed up with each other, color and shape our perspectives and thus our expectations. Even when our rational impulses tell us what makes the most sense, our “guts” are telling us something very different. Trying to make good decisions in that context is never easy. As Ben Carlson emphasizes in his excellent new book, “[I]nvesting really comes down to regret minimization.” We all have to muddle through as best we can and try to do just that.

Copyright © R. P. Seawright, Above the Market