Up At Night

by Ben Inker, GMO

Executive Summary

Investors spend a lot of time worrying about what can go wrong for their portfolios. This is a worthwhile and, indeed, essential exercise, but the obvious corollary activity, protecting a portfolio from what can go wrong, is less clearly a good idea. This seeming paradox can be disentangled by recognizing that it is impossible to determine if you are taking an appropriate amount of risk without understanding what the downside is for your portfolio, which means you simply have to do the exercise of understanding what can go wrong.

Buying insurance for your portfolio to reduce that downside, however, is a much dicier proposition, leaving you generally either paying so much for broad insurance that you might as well own less in risky assets in the first place or buying insurance for such a narrow range of events that you haven’t protected your portfolio that much at all. This is not universally true, and it can make sense to hedge a piece of the risk that goes along with an asset whose other characteristics you like. It can also make sense to shift the assets you own in the first place given the particular risks that seem most important for your portfolio.

For example, in our Benchmark-Free Allocation Strategy we are currently hedging a piece of the risk in emerging markets to protect against the possibility of US dollar strength, and we are choosing to hold alternative strategies and inflation-linked bonds versus equities and conventional bonds to protect against the risk of rising inflation and rising discount rates.

Introduction

Perhaps the most common question I get from clients is “What keeps you up at night?” This question is a shorthand way of asking what potential economic, political, or market events are we most worried about, and what, if anything, are we doing in our portfolios to deal with them. It is the kind of question that any responsible investment manager is supposed to have a thoughtful answer to, and within the context of the couple of minutes that it is generally expected that I will dedicate to answering a question, I will do my best to answer it thoughtfully. But risk is a more nuanced issue than most people make it out to be, and in this quarterly I will try to dig further into the issue than I can in a couple of minutes. Whether it still seems a thoughtful answer I will have to leave to the reader.

The business of investing is inherently about taking risk. While there are some risks it is possible to avoid taking – you don’t have to worry about the risk of financing being taken away from you if you don’t lever your portfolio, for example – some important risks are unavoidable.1 The reason why the returns to stocks are higher than T-Bills is because they involve more risk of loss in a depression. The same is true for credit, real estate, venture capital, infrastructure, and everything else generally referred to as “risk assets.” Even government bonds with longer maturities than T-Bills generally have to offer a higher yield to compensate for the risk of inflation and rising interest rates. As a result, probably the most important question in determining the long-term returns investors can earn is how much risk they are prepared to take. Those prepared to take more risk should generally expect higher returns in the long run. But taking too much risk can also lead to disaster for investors. An investor holding a 60/40 S&P 500/Treasury bond portfolio in September 1929 would have had 39% of his money remaining by June of 1932. An investor holding 100% S&P Composite would have retained 18% of his money, and one leveraging his investment in the S&P 2:1 would have retained 1.8% of his money. Losing 61% of your money is no fun, but losing 82% is an awful lot worse, and losing 98.2% is too horrifying to contemplate. The brave investor who somehow kept going with the leveraged strategy would, indeed, have recovered eventually, but it’s hard to imagine how one could actually stick to such a strategy.2 The 100% S&P strategy outperformed the 60/40 strategy by about 1.5% annually since 1920, so there was, in fact, a higher return for the additional risk. Whether an investor would have been able to take that additional risk, however, is another matter.

How much risk can you take?

Determining how much risk you can take as an investor is a crucial exercise. There are at least two aspects to it, generally referred to as risk capacity and risk appetite. Plenty of commentators have written on these concepts, so I won’t spend a lot of time discussing them here other than to say it is a bad idea to ignore either aspect. Risk capacity refers to the extent of loss a person or organization can withstand without having to significantly change spending patterns. An endowment that is responsible for covering a relatively small percentage of an institution’s budget probably has more risk capacity than a foundation, where spending from the corpus must cover 100% of spending. And a 25-year-old who is 40 years from retirement probably has more risk capacity in his retirement savings than a 70-year-old who relies on those savings for a large portion of his necessities.

It’s hard to quarrel with the idea that different investors have different risk capacities. It is easier to argue that risk appetite is more about a lack of education on investing – an investor who has much less risk appetite than risk capacity will wind up leaving a lot of return on the table over the years for no good objective reason. But the converse problem is quite real as well. An investor who sold risk assets in 2009 due to heightened fears of depression or just the shock of the losses suffered in the financial crisis clearly held a portfolio too risky for his risk appetite, regardless of his true risk capacity.

Calculating the risk of your portfolio is a complex exercise, so I’d like to keep to the conceptual end of things here. In thinking about risk for a portfolio, I believe you need to worry about both a few risks that are eternal – the risk of depression and the risk of unanticipated inflation come to mind as eternal risks – as well as risks that come out of the unique economic, political, and environmental issues that are specific to the world today.

Why not hedge your risks?

Any homeowner who fails to insure his house against theft and damage is rightly considered to be reckless. Plenty of insurance products are available for portfolios, so why not insure your portfolio, too?3 There are a number of reasons why the analogy fails. First and foremost, a house that is one quarter destroyed is not the same as a house that is three quarters the size. If a fire or tornado has destroyed one of the walls of your house it has to be repaired. You can’t decide to avoid the affected rooms and go on with your life otherwise unaffected. But a portfolio that has lost one quarter of its value is simply a portfolio that is 75% of its original size. It is disappointing, to be sure, but it doesn’t actually impair the proper functioning of the portfolio. It is possible that its smaller size does functionally impair your ability to live off of it, however. This is where risk capacity comes in, and if a 25% loss is unacceptable for whatever reason, it makes sense to build a portfolio where the risk of such a loss is very low.

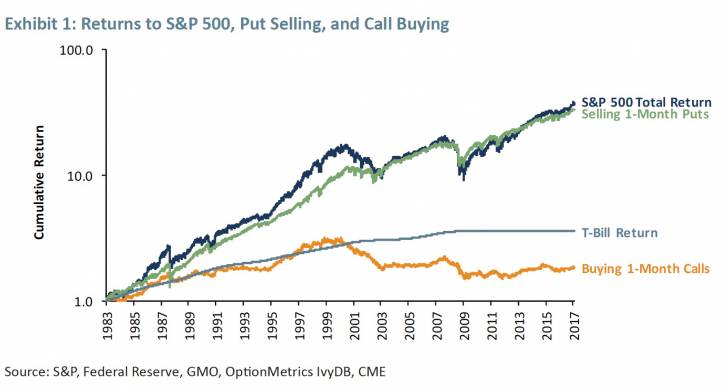

Let’s imagine that a 75/25 stock/bond portfolio has a 10% chance of a 25% loss, and you want to reduce that probability to 5%. You could move to a 60/40 portfolio and (let’s assume) that reduces the probability of loss to an acceptable level. The trouble is that you know that the 60/40 portfolio has a lower expected return because it has less in stocks. But if you bought a put on some of your stock portfolio to reduce the expected losses, you could afford to keep more stocks in your portfolio. Should you do it? The short answer is probably not.4 Stocks tend to give a higher return than bonds because their risky nature makes investors price them cheaply enough that the cash flows available to shareholders are worth more than the interest payments on high quality bonds. A put option moves that risk to some other investor, and that investor needs to be enticed into taking that risk by receiving a premium on the option approximately equivalent to the return to equities. Exhibit 1 shows this clearly. It shows the cumulative return to four strategies – owning the S&P 500, selling puts on the S&P 500 and otherwise investing in cash, buying calls on the S&P 500 and investing the remainder of your capital in cash, and simply rolling T-Bills. The chart starts in 1983 because that is when listed options on S&P 500 futures came into being.

Since 1983 the S&P 500 has returned 11.2% annualized (a still impressive 8.3% after inflation). Put selling, which gives you all of the downside of the stock market and none of the upside, returned 10.9% after estimated transaction costs, almost exactly the same. By contrast, the call buying strategy, which gives all of the upside of the stock market and none of the downside, returned 1.8% after estimated transaction costs, 2% a year less than T-Bills! Markets are by no means efficiently priced at all times, but the assumption that you can keep the returns of owning stocks while getting rid of the downside has turned out to be almost exactly as wrong as it deserves to be.

Buying specialized insurance?

So while you could use puts to reduce the downside of your stock portfolio, it is a pyrrhic exercise. You might as well just own less in stocks in the first place. Frankly, this is exactly how it should be. You don’t buy insurance on your house with the expectation that the losses you incur will be greater than the premiums you pay over time. Any insurance company that priced its product in that way would go out of business pretty quickly. It makes sense to buy homeowners insurance despite the fact that the expected return to buying the insurance is negative, because the alternative of altering your house so that the risk of loss is removed is either impractical or impossible. With a portfolio, you can alter it to change the loss characteristics by reducing the weight in risky assets, and that is likely to be a superior strategy to trying to buy insurance for the portfolio.

But there are other ways to try to protect your portfolio. While general “loss insurance” may be too expensive to be practical, it may be possible to take advantage of correlations between assets to try to get the insurance more cheaply. To stick with the insurance analogy, protecting your house against loss from fire may be expensive, but if your insurance only kicks in if the fire is started by a cow knocking over a lantern in a shed, it will be a lot cheaper; if you were living in Chicago in 1871, that insurance would have worked out perfectly.5 In portfolio terms, there are many ways to build such a hedge, depending on what you think will be the underlying cause of the trouble. If you were sitting in late 2006 and decided that you were worried about a market fall stemming from a drop in the US housing market, you could have hedged your portfolio by buying protection on mortgage-backed securities. This would have worked out spectacularly well. If you had been willing to spend 0.11% of your portfolio annually on protection in the form of the ABX-2006-2 AAA, you could have covered 100% of your portfolio with protection should the underlying subprime mortgages go bad. By the time the stock market hit its bottom in 2009, you would have paid about 0.3% total in protection, but your protection would have made you 70%. Now admittedly this was probably the most mispriced insurance policy in the history of the world, and had you managed to do what I suggest here Christian Bale might well have played you in the movie version of your exploit.

And that makes calling such a trade “insurance” a little misleading. If you can find a massively mispriced security, you will almost certainly be able to improve the expected return of your portfolio by exploiting the mispricing. If the trade is negatively correlated with the rest of your portfolio, so much the better, but I would submit that if you can pay 0.3% for a 70% gain it really doesn’t matter what that trade’s correlation was with the rest of your portfolio. The rest of your portfolio will have been a waste of time and money by contrast.

But let’s imagine a world with an all-knowing insurance company as your counterparty. This company is absolutely guaranteed to properly price any insurance it sells you, so that it has an appropriately negative expected return for you and positive return for it.6 Is there any circumstance in which you want to buy insurance from this company? Quite possibly. You may have a portfolio for which a particular risk is more important than it is for other investors and where an ability to hedge the risk buys you the ability to own more attractive assets than you otherwise could. While it generally doesn’t make sense to hold an asset and try to get rid of all of its risk, if there is a particular piece of its risk that is stopping you from owning as much as you’d like, it may make sense to hedge that risk and continue to bear the others.

An example for us currently is emerging market currencies. In our Benchmark-Free Allocation Strategy, the single largest piece of our equity portfolio today is emerging market stocks. We like them because they look a good deal cheaper than stocks in the developed world. But given their large weight in the portfolio, there are potential events that could hurt our portfolio more than a traditional portfolio, so even if the market is pricing the hedge “correctly,” we may want to hedge against these potential events. A pertinent risk today for emerging equities is a potential border adjustment tax in the US. Such a tax would be expected to cause the US dollar to appreciate against foreign currencies without any corresponding increase in foreign companies’ earnings from the US. At the moment, the risk of such a tax coming into existence is fairly low despite some support in the House of Representatives. But if it did happen, it would create a meaningful loss for our portfolio without causing the expected return to the damaged asset (emerging equities) to rise.7 Let’s imagine, for simplicity’s sake, that passage of a border adjustment tax would cause the US dollar to appreciate by 10%.8 We could potentially do a few things about this risk. First, we could own less in emerging equities to reduce the impact. The trouble with that is we think the emerging equities we own are around 5% per year better in expected returns than the next best alternative. Selling an asset with an expected gain of 5% for a perhaps 10% chance of a 10% loss is very unappealing. We could currency hedge our emerging equities, but emerging currencies also look cheap to us and generally have a high hedging cost against the US dollar. Fully hedging the currency of the emerging countries would cost over 2.5% on an expected basis. In fact, the only emerging currency that doesn’t look at least mildly cheap to us against the US dollar is the Israeli shekel, which is not a material exposure in our portfolio and does not act much at all like other emerging currencies most of the time. But the next least attractive currency in emerging is the Korean won, which looks only a few percent cheap versus the US dollar and has interest rates much lower than the average in the emerging world. This combination makes for a lower hedging cost. Furthermore, the Korean won has both a high empirical beta to emerging currencies and seems absolutely in the cross-hairs of the kind of country a border adjustment tax is designed to hurt – an export-oriented manufacturing powerhouse with a relatively small domestic market. Should a border adjustment tax

come into being, it seems to us very likely that the won would get hit, and in the more likely event that it does not, our expectation of the cost of the short position is about 1% to 1.5% of the notional per year. Our best guess is that the hedge will cost us some money. But if the alternative is to own less in emerging equities, it makes sense to do it anyway, because a 1.5% expected cost is a lot less than losing 5% by having to sell that amount of emerging equities.

Moving beyond the hedge

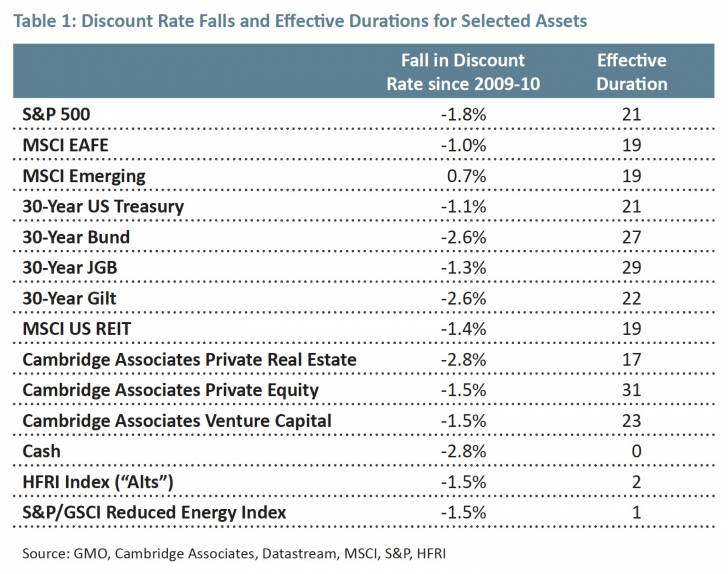

But a broader benefit of thinking about the downside of your portfolio is that it can help you make better decisions about the actual assets you own, not just the question of what hedges (if any) you want to put in your portfolio. As I wrote about in Hellish Choices,9 the discount rates associated with most assets seem to have fallen considerably over recent years. Given that the fall has been relatively uniform, it isn’t inherently unsustainable. Table 1 shows an estimate of the changes in the apparent discount rate for a range of assets from 2009-10 to year-end 2016.

While some assets have not been affected (emerging equities are the standout in this regard with an apparent rise to their discount rate), if we think of this as a general fall of about 2% in the discount rate applied to assets, such a fall does not change the relative attractiveness of assets, assuming the shift is permanent. If stocks used to deliver 6% real and are now priced to deliver 4%, that may be okay if at the same time bonds that used to deliver 3% real now deliver 1% real. The difficulty is that if discount rates were to rise again, it will hit different assets in a materially different way, which is shown in Table 1 in the “effective duration” column. Equities and long-term bonds are long-duration assets and will clearly be hurt in such an environment; cash and alternatives are short-duration assets and would be much less affected.

Potential driver of discount rate back-up

So if we are otherwise trying to own assets with relatively good expected returns on our forecasts, a significant risk for our portfolio (and most portfolios) would be an event that causes discount rates to back up significantly. This would hit long-duration assets particularly hard. So if today we are faced with two assets of similar expected returns, we can preferentially buy the shorter-duration one. Under normal circumstances this isn’t necessarily a good idea. If discount rates are as likely to fall as rise, long-duration assets are a good thing because a long-duration asset will gain more in price for a given fall in discount rates than it will lose for the same size rise.10 But today’s circumstances do not appear to be normal. While it is possible that discount rates will continue to fall from here, it’s hard to see why you’d want to put a high probability on it. Rising discount rates, on the other hand, would see valuations move closer to historical levels, and even if that is not considered a certainty it’s awfully hard to discount it as a meaningful possibility.

And we have, indeed, shortened up the duration of the Benchmark-Free Allocation Strategy, both by moving money that would otherwise be in equities into alternatives and by having a pretty short-duration fixed income portfolio. But we can go a step further. If we try to think about the circumstances in which discount rates will have to rise significantly, an extremely plausible driver would be a return of inflation pressures in the global economy. After all, the “stylized fact” that the secular stagnation argument has been trying to explain is that inflation has remained low in the face of monetary policy that would have been expected to encourage a rise. If it turns out that this was only a temporary phenomenon, average interest rates will need to be higher than markets are expecting today, because the secular stagnation scenario that so many investors have bought into will be proved wrong. So beyond thinking about the duration of assets, we can think about their expected returns in the event of inflation, because an inflation event is probably the most likely reason why discount rates come up significantly.

Here we probably want to separate out the impact of duration and the underlying cash flows. Equities tend to do poorly in inflation, but their cash flows actually hold up fine. The trouble is that P/Es fall. While that is an important effect, we are taking that into account when we think about duration and a potential rise in discount rates. We don’t want to double count the trouble in the event of inflation. So what we hold in equities is probably okay here. Alternatives, which are the shorter-duration risk asset we own instead of equities, shouldn’t be a particular problem either, because their cash flows come quickly enough not to be hugely impacted by inflation, barring a hyperinflation event. But on the fixed income side, insofar as we own duration, it makes a lot of sense to make it inflation-indexed duration, in the form of TIPS, rather than traditional nominal bonds. This is not to say that TIPS will do well in the event of inflation. Rising inflation would almost certainly drive the Federal Reserve to increase rates by more than the increase in inflation, so TIPS will take losses, but their losses would be significantly lower than those of conventional bonds.

But even here there is an important nuance to be aware of: TIPS will almost unquestionably outperform conventional bonds in the event of unanticipated inflation. They will also very likely underperform in the event of a depression. While there have been a few inflationary depressions in history, and government policies in depressions can wind up leading to inflation later, generally speaking, inflation surprises to the downside when the economy tanks. And for portfolios with a lot of equities or other risk assets in them, depression is the “worst-case scenario” for the portfolio.

While unanticipated inflation seems like a particularly salient risk today, protecting against inflation at the cost of increasing vulnerability to depression is far from an easy decision. Even if choosing to own TIPS versus conventional bonds is not a “hedge” in the way that buying puts on a stock portfolio is, it still isn’t free. But for our Benchmark-Free Allocation Strategy, given that we have a lower than normal allocation to risk assets, we believe we can afford the lost protection against depression that would come with holding conventional bonds and that the trade-off is a good one. Without having done the analysis on the downside scenarios for our portfolio in the first place, we would not be in a position to conclude that.

Conclusion

By analyzing the vulnerability of our portfolio both against eternal risks and today’s particularly relevant risks, we have gained knowledge we can use to help us decide whether there are any risks it makes sense to hedge against today, as well as to help us alter the underlying asset mix to improve the portfolio’s robustness. Occasionally, markets will be sufficiently mispriced that we can get insurance for free, or actually be paid for it. Such times are to be treasured, but they are the exception rather than the rule. Most of the time, hedging and asset shifting decisions are not easy and involve trade-offs that have real costs to them, either in terms of lower expected returns or worse returns in a scenario that we may well care a good deal about. Today, we think the potential of a border adjustment tax is a meaningful one to our portfolio given the way the portfolio is positioned. We also think that the risk of unanticipated inflation is worse than usual, given how low discount rates are across asset classes.11 The latter risk rises to the level of causing us to lose some sleep, and we have tried to position the portfolio to mitigate some of the risk. Our goal is to improve our expected outcomes in the events we fear without paying too large a price in lower expected returns or increased risks against other scenarios. This is not always possible, and when it isn’t, we’ll suffer some insomnia. Losing sleep isn’t fun, but overpaying for sleep aids will wind up hurting in the long run.