Can China's Cracks be Repaired

by John Canally, Chief Economic Strategist, LPL Financial

KEY TAKEAWAYS

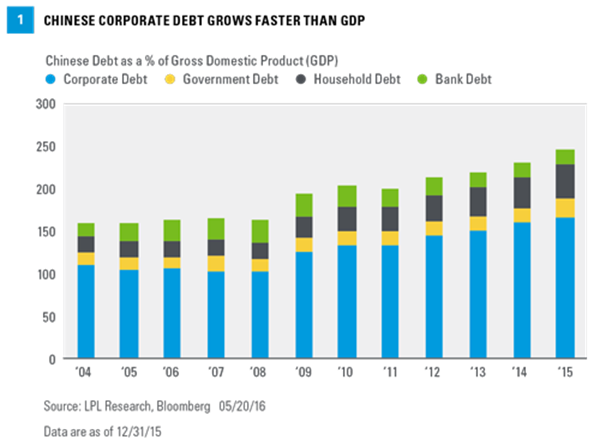

· China’s recovery from the global economic crisis of 2008 was built on significant and unsustainable debt levels.

· Total Chinese debt is believed to be $30 trillion, with consensus building that something must be done.

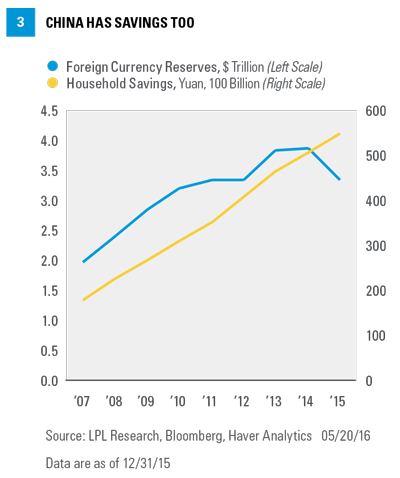

· Despite its debt problems, China still has resources available to combat the problem.

Can China’s Cracks be Repaired?

China’s increasing debt may be approaching the tipping point. China’s economic growth has been driven largely by capital investments—buildings, roads, factories, even entire cities—since the 1990s. In the process, Chinese regional governments, banks, and companies built up large debts. As the global economy slowed, Chinese leaders have increased infrastructure investments to maintain employment and “social harmony.” However, these investment programs have added to the debt problems. Increasingly, the conversation about Chinese debt, both internally and externally, is about the economic risks it has created. Although unlike other highly indebted nations, China has options. Most of its debt is owed internally; it controls its own destiny, unlike Greece or Argentina. It also has high levels of foreign currency reserves and domestic savings.

China’s debt: How much is too much?

The absolute number is scary. Chinese entities—its government, companies, and households—now owe approximately $30 trillion. We, along with most market participants, believe the best way to evaluate a nation’s debt load is by looking at debt relative to gross domestic product (GDP) [Figure 1]. After all, a nation’s GDP will provide the wherewithal to repay that debt. From 2004 to 2008, overall Chinese debt was fairly stable at just over 150% of GDP. The government responded to the financial crisis in 2008 by creating a $600 billion fiscal stimulus program, over 13% of GDP at the time. Much of this stimulus was debt fueled and put in place by encouraging corporate borrowing. Some of this borrowing resulted from traditional monetary policies like lowering interest rates and amending rules to make credit more accessible. But much of stimulus came from the government’s control of the economy through its state-owned enterprises (SOE), the major companies that at the time comprised 40% of the economy. Although the state sector has shrunk in relative terms since then, it still represents over 30% of the Chinese economy.

Evaluating China’s Data

As a general rule, evaluating Chinese data can be challenging due to heavy government intervention in the economy. The distinction between the private and public sectors in China can be blurry, if not totally illusory. Yet, when evaluating the China’s debt, these distinctions become much less important. The default of a major SOE will reflect just as negatively on the government had it been a technical government default.

Though China’s debt has been worrisome for some time, the concern has been growing recently. Figure 2 shows two ways to gauge market fears of defaults in China. Credit default swaps (CDS) on Chinese debt provide a direct window into major market participants’ views on Chinese debt. CDS represent the costs of insuring against a Chinese default. Major global financial investors and institutions trade these contracts. Though the cost of insuring Chinese debt can be volatile and is off its recent highs, the overall upward trend in price shows the market’s increasing concern. The fact that there are even traded contracts like this is evidence the market is looking to price some probability of default. We also show the decline in the value of the Chinese yuan against the currency of China’s major trading partners, not just the U.S. dollar. Many factors influence a currency’s value. However, fears of economic instability and possible default have contributed to recent currency weakness.

A credit default swap (CDS) is designed to transfer the credit exposure of fixed income products between parties. The buyer of a credit swap receives credit protection, whereas the seller of the swap guarantees the credit worthiness of the product. By doing this, the risk of default is transferred from the holder of the fixed income security to the seller of the swap.

Authoritative Concern

China watchers were struck recently when an article published in the Chinese People’s Daily, the official news outlet for the Communist Party (and therefore, the Chinese government), condemned the country’s reliance on leverage. Debt was referred to it as an “original sin” that leads to subsequent risks. The article also called on the government to stop resorting to additional debt-fueled stimulus to prop up failing industries and zombie SOEs. The interviewee was identified only as “an authoritative person” believed to be either President Xi Jinping or one of his most senior advisors. That an article so openly critical of government policy was published in an official news outlet shows that the level of concern in China is high and reaches the top levels in government.

China Cracked but not shattered

China’s debt problems are bad, but not insurmountable, for several reasons. First, most of the debt is owed internally. Furthermore, to the extent that the government is often a partner, officially or not, with the lenders (mostly banks) and debtors (mostly SOEs), the Chinese asset/liability equation is closer to balance than many people understand. In many instances, though not all, the Chinese government owes money to itself. When countries typically have debt problems, it’s because they have external creditors that cannot be satisfied. Recently this has been the situation with Greece and Argentina. Greece had external debt equal to over 75% of its GDP. That figure for China is under 10%.[1]

The other bit of positive news from China can be seen in Figure 3. We see the steady growth in household banking deposits in China. The Chinese people save a lot, approximately 30% of their income, compared to roughly 5% savings rate for the U.S. As their income has grown, so have their savings in absolute terms. This provides the ability for Chinese companies and government entities to finance their expansion without having to look overseas. But China’s high savings rate has proven to be as problematic as it appears virtuous. By most accounts, the Chinese save too much and spend too little, undermining the government’s attempts to rebalance the economy away from investment and toward consumption.

The other item displayed in Figure 3 is Chinese foreign currency reserves, which declined last year as the government sought to stabilize both the economy and the value of the yuan. But even so, with over $3 trillion in total reserves, including approximately $2 trillion in U.S. Treasury bonds, China has a massive war chest that can be used to at least pay off its foreign creditors if need be.

How Bad are the Cracks in the China?

So what is everyone, including senior Chinese leaders, worried about? The concern comes from the realization that—assuming the debt level is manageable—fixing the problem will cause unrest within the country. Bad debts would presumably result in layoffs, primarily by the large SOEs that employ so many Chinese workers. The economic uncertainty that would result from widespread defaults in China would likely further encourage savings by Chinese consumers, further weakening the economy by curtailing consumer spending.

If one person’s debt is another one’s asset, the difference between the ultimate winners and losers may be vast. Officially, China’s bankruptcy laws became effective in 2007 and are very similar in structure to U.S. and European laws. In practice, the broad discretion afforded judges and the influence of the politically connected results in relatively few cases with largely uncertain outcomes. Combined with the questionable value of some underlying assets, the holders of Chinese debt could see a significant reduction in their assets.

The good news is that most of the impact of these changes would be felt within China. We believe that the government would intervene in a way that would limit global impact—not because the government is necessarily concerned about the damage done to foreign companies, but because it will make sure that basic Chinese needs are being met. For example, if China needs to import raw materials such as oil and coal to run its economy, it will do so. It may be a different SOE that is doing the purchasing, but the government will do what it can to maintain its economy. These imports have slowed down, and may continue to do so. But it is not Chinese debt levels that mandate the slowdown, it’s the realization that the Chinese economy no longer needs and cannot support such a high level of infrastructure investment. Debt is the symptom of China’s problems; it is not the root cause of them.

Conclusion

China remains a heavily indebted country, but one that owes most of the debt to itself. The political climate in China clearly shows a willingness to discuss Chinese debt, and that in and of itself is a significant development. Because China owes its debt to itself, the major impacts of China dealing with its debt problems will be felt within its borders. The timing is uncertain, however, and this process will be very painful for the Chinese people and for Chinese companies.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results. Any economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful. All indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

Investing in stock includes numerous specific risks including: the fluctuation of dividend, loss of principal and potential illiquidity of the investment in a falling market.

Investing in foreign and emerging markets securities involves special additional risks. These risks include, but are not limited to, currency risk, geopolitical risk, and risk associated with varying accounting standards. Investing in emerging markets may accentuate these risks.

Gross domestic product (GDP) is the monetary value of all the finished goods and services produced within a country's borders in a specific time period, though GDP is usually calculated on an annual basis. It includes all of private and public consumption, government outlays, investments, and exports less imports that occur within a defined territory.

[1] Data through 2014 are available from the World Bank at data.worldbank.org.